The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

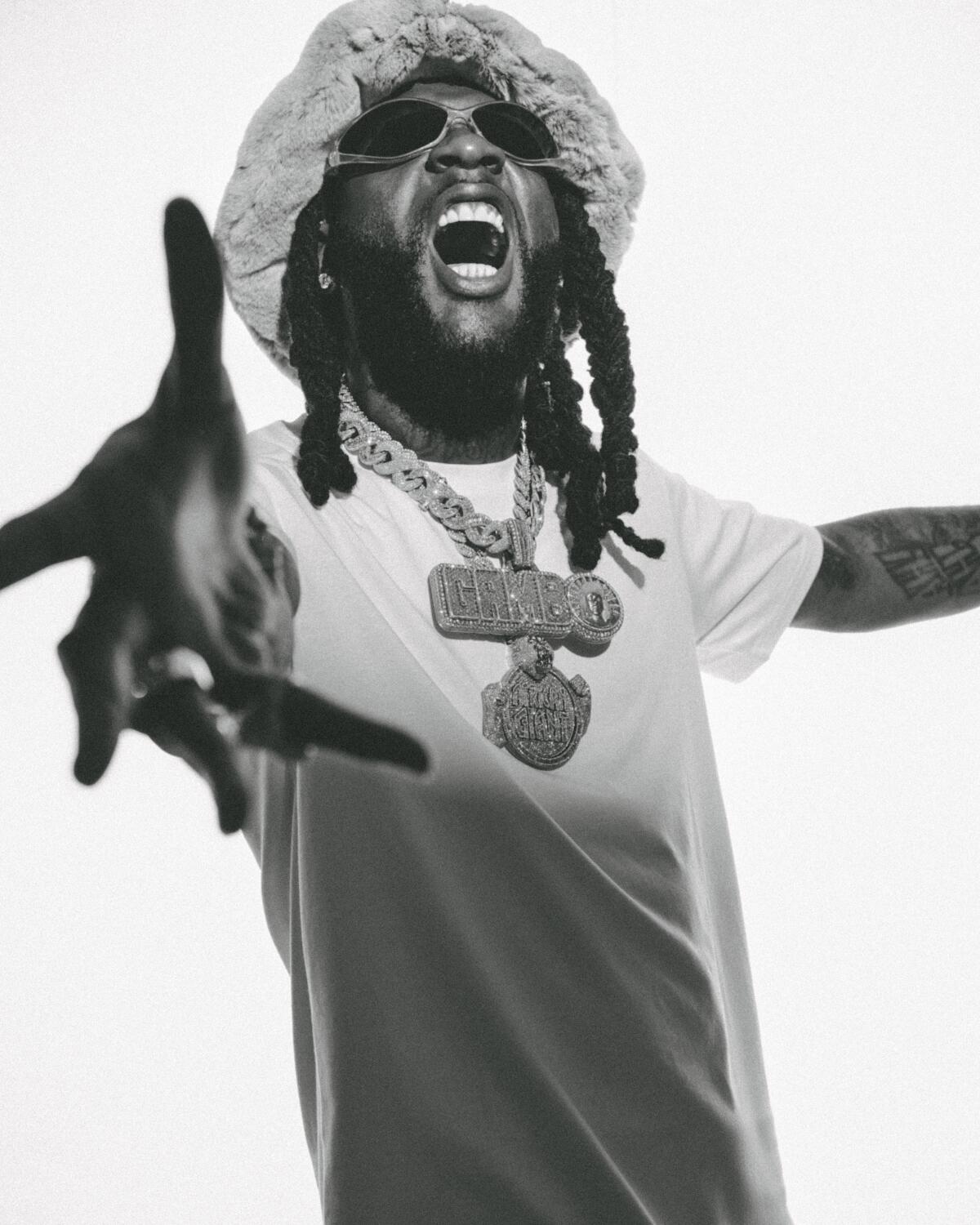

QUEENS, N.Y. — Until recently, Burna Boy didn’t have a phone.

Owning arguably the most essential item in the internet age simply didn’t interest him. His sister called it an act of self-preservation lasting nearly three years, making him nearly impossible to reach for those outside his inner circle.

“He just got a phone number in the past year,” says his sister, Ronami Ogulu. “He didn’t even have WhatsApp.”

In early July, however, Burna Boy arrived with his very own iPhone at Sei Less, a glitzy Asian fusion restaurant in Midtown Manhattan that’s popular with rappers, athletes and even the mayor of New York. Adorning the walls of the downstairs “emerald room” were at least 100 bottles of Don Julio 1942 — the same liquor that was in the glass in front of him, chilled by one jumbo-sized ice cube.

It’s one of several birthday parties for the man born Damini Ebunoluwa Ogulu, who turned 32 less than a week before our conversation. Camouflaged into a couch was a gift bag from his label, Atlantic Records, which contained an action figure of Wu-Tang Clan pioneer RZA and yet another bottle of 1942. In the hours before his arrival, his team scrambled to put the celebration in place, fast-tracking lobster spring rolls, lychee martinis, chicken dishes and fried rice from the kitchen to the private room. “Tell them Obama’s in the house,” Ronami quipped to the waiter.

Truthfully, the former president’s heart might have skipped a beat in Burna Boy’s presence. The self-anointed “African Giant” has landed on five of Barack Obama’s biannual playlists, including the three most recent editions — twice in 2022 for his breakup-song-slash-party-starter “Last Last,” and this summer with “Sittin’ on Top of the World,” which borrows the ’90s New York bounce of Brandy’s “Top of the World” and features 21 Savage.

Burna Boy’s music pulls from all corners of the diaspora, merging afrobeats with hip-hop, reggae and R&B while singing in a blend of languages to create a sound he calls afrofusion. But the Nigerian superstar’s all-encompassing sound also falls in line with his larger message: to amplify Pan-Africanism and unify Black people around the world through the rhythms.

“They’ve successfully broken us apart, to where many of us don’t even want to identify with each other,” he tells me at Sei Less. “The primary objective for our people should be unity, and to build a bridge between us that can never close or break. With the music, I try to play my little part in trying to do that.”

The day before we meet, he became the first African artist to headline a concert at a U.S. stadium when he turned New York’s Citi Field into a 41,000-strong birthday celebration. Early in the show, four white cakes surrounded him as he rose atop a platform into the night air, singing the rousing “It’s Plenty” after telling the crowd it was time to celebrate.

When he wasn’t floating above the stage, he danced across it like it was his living room, leaping in the air behind smoke blasts or performing stop-motion routines during a beat breakdown. Halfway through the two-hour performance, sweat had turned his shimmering white garb into a sopping gray getup, and he drew ear-piercing screams from the crowd once he finally removed his shirt to perform “Sungba.”

A moment of this magnitude wouldn’t have been possible even 10 years ago, when African music’s foothold in America was a fraction of what it is now. But steadily, Burna Boy has taken afrofusion from Nigeria to the U.K. and finally the world, powered by a relentless tour schedule and hits such as his 2018 anthem “Ye.”

“The story of me in New York is basically the story of my whole career,” says Burna Boy. “There were no elevators. It was a straight staircase. I went from PlayStation Theater to Gramercy Theatre to the Apollo to Madison Square Garden and finally Citi Field.”

“There’s a new connection between the motherland and us in America,” says RZA, who has become a collaborator and mentor of sorts to Burna Boy. “To see Burna sell out that stadium is a perfect example of that.”

Never one to rest on his laurels, Burna Boy will release his seventh studio album, “I Told Them…,” on Aug. 24. The title offers up his flippant response to nonbelievers who’ve attempted to discredit him, both in the beginning of his career and now.

“To this day, there’s many Nigerians who can tell you an American rapper who just started their career, and they’ll say they’re bigger than Burna Boy,” he says. “They don’t understand it. They’ll say, ‘There’s no way someone who talks like me, can even be on the same level as an American artist.’”

Across the album, he attempts to reconcile his efforts to promote Pan-Africanism against doubters looking to minimize his contributions. On the intro track “I Told Them,” there’s a stubborn declaration of triumph after manifesting the proclamations he made years ago; emotion pokes through on “Thanks,” as he cries out to God when jealousy and nagging have pushed him to the brink.

That’s not to say his ears are shut off to constructive criticism; making a concise project was the ultimate goal, after his most recent albums stretched as long as an hour. The focused, militant energy rings most true on “On Form,” which brings a gripping baseline to anchor his charged vocals.

“Listening to the album now, it just sounds like a battle,” says Matthew “Baus” Adesuyan, Burna Boy’s A&R executive and co-founder of Bad Habit Records. “Especially with all the kung-fu samples from Wu-Tang Clan and Shaolin, it sounds like we’re going to war. That’s his energy now.”

As the fusion genre Afrobeats continues to expand its footprint here in the U.S., a growing number of fans are journeying to its source: West Africa.

As a child, Burna Boy idolized the Wu-Tang Clan; on his forthcoming album, he leans into their shared love for all things Shaolin while bringing founding members GZA and RZA into the fray. RZA recites the 12 Jewels of Islam on “Jewels,” instructing Burna and listeners of the essential elements one must strive for to reach a fulfilling life.

The jewel of justice has proved to be the most elusive for Burna Boy to possess — “We live in a world where there’s almost no such thing,” he says. “Coming from where I come from, our definition of justice has been tainted to zero.”

Still, he feels it’s not only possible, but that it’s his duty to master the 12 Jewels. Does that mean the world has to reach harmony before he can find inner peace?

“I have a lot of conflicting answers to that question,” he says after a pause. “On one hand, yes, the world needs to heal before I can do that. But I also feel, we’re gods, and we need to heal ourselves first. And then, everything else will fall into place. It’s almost like we say, ‘Let there be light,’ but then the light comes and we don’t see it, because we’ve been in the dark so long.”

“I can feel what Burna means,” adds RZA, “by saying it’s hard to see justice in this life, especially as a Black man. But it’s a self-balancing scale. Politically, the world is responsible for freedom, justice and equality. But spiritually, every man will qualify or disqualify himself.”

Born in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, Burna Boy spent significant time on the road as a child. His mother ran a language school that hosted immersion trips for the students, allowing her to take the family across West Africa and into France and the United Kingdom.

By the age of four, he had fame on his mind, telling his primary school teacher he wanted to be a rock star when he grew up.

“He’d just start dancing everywhere we go,” Ronami says.

Music always ran in the family — his grandfather is Benson Idonije, esteemed Nigerian music critic and the former manager of Fela Kuti. Growing up, Burna Boy didn’t resonate much with his grandfather’s tales of the legendary afrobeat pioneer, gravitating instead to hip-hop that had crossed the Atlantic, such as Naughty by Nature, DMX and the Wu-Tang Clan.

“For a long time, us Nigerians wouldn’t even hear African music on the radio,” Burna Boy says. “It was really all American music.”

As hip-hop celebrates its 50th anniversary on Aug. 11, The Times looks back at the artists, songs and innovations that changed the course of popular culture.

Once he’d committed himself to music in his late teens, he threw himself into Idonije’s five-digit record collection, flipping highlife, afrobeat and jazz vinyls on the turntable for hours in his garage. He fell in love with the saxophone, in large part because his grandfather loved it and helped him understand the expressive emotion a player can pour into it.

Seeing his dedication, his family went all-in as well.

Burna’s mother, Bose Ogulu, became (and still serves as) his manager, focusing on brand deals, contracts and other business moves. Ronami assumed a role as his stylist and currently handles branding, media partnerships and strategy development. And more than a few times, he’s called on his grandfather with questions when putting a new project together.

“Very few families have been able to manage that in our industry,” says RZA. “The Marleys did it. But the majority of artists leave their families. It’s so good to see him bringing his family with him.”

Together, they’ve taken the family name from Port Harcourt to some of the world’s biggest stages, including a date at the Hollywood Bowl in 2021 and a sold-out gig at London Stadium in June that brought out over 60,000 people. Burna Boy won a Grammy for global music album for 2020’s “Twice as Tall,” and has a good shot at raking in more via the newly created African music performance category, although he remains apprehensive of how much weight the award will hold.

“I do feel somewhat responsible for [the new category], which is nice,” he says. “At the same time, what is it really? Is it a consolation category? Will it hold as much prestige? I’m waiting to see.”

While reaching new heights in his bid to be bigger than a genre, there’s much more he doesn’t yet have the answers to. He draws a blank when asked what brings him joy aside from music, and similarly can’t identify what he’s most proud of accomplishing in his life or career.

An everlasting touring schedule on top of dropping five projects in six years has left him little time to reflect, and he wearily admits a break may be in the near future to recalibrate. For now, the battery remains charged; he sprints up the stairs after our conversation for a photo shoot, and then bounces out the door to make a just-booked appearance in Coney Island.

“I don’t know how I stay grounded, to be honest,” he says. “I can’t really tell you everything that brings me happiness. All I know is what I’m sure about, and I’m sure music is life for me. I have to deliver.”

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.