Appreciation: Sinéad O’Connor was right all along

- Share via

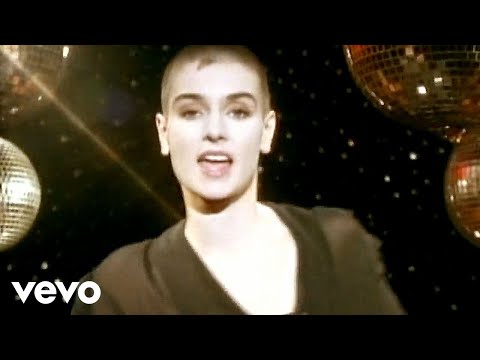

For many years, like most of the world, what I knew about Sinéad O’Connor was limited to three facts: her head was shaved, she had a mega-hit in 1990 with “Nothing Compares 2 U” and two years later her career came crashing down when she destroyed a photograph of Pope John Paul II on “Saturday Night Live.”

After that, whenever I saw her name, or names (she later went by Magda Davitt and Shuhada’ Sadaqat), it was invariably tied to tabloid headlines: She’s married, she’s divorced. She’s come out as a lesbian — actually, no she’s not. She’s been ordained as a Catholic priest. Hold that, now she’s a Muslim. She’s been diagnosed as bipolar — scratch that, it’s borderline personality disorder. Or maybe her mood swings are because of her hysterectomy. Or drugs. Or all of the above.

I had no idea that long after she stopped making pop hits, O’Connor released nearly a dozen albums (many excellent), recorded songs for film and TV, collaborated with other artists and contributed music to causes including HIV/AIDS awareness and Black Lives Matter. I didn’t know that many of the public statements she made over the years were lucid and insightful, and that she often got them right, especially about important issues.

On Wednesday, O’Connor’s family announced that the singer had died at age 56. No cause of death was given.

Sinead O’Connor, the haunting singer who shot to fame in the ‘90s and sparked controversy with an anti-Catholic protest on live TV in the U.S., has died at 56.

To understand her inevitable rise and fall from pop stardom, it’s important to consider that O’Connor’s life began in theocratic Ireland, in the 1960s, where she suffered abuse at the hands of her devoutly religious mother. When her parents split, in her early teens, O’Connor’s father was awarded custody, nearly unheard of in a country where divorce was illegal and courts invariably sided with mothers in cases of separation.

By then O’Connor had already been hauled into police stations for shoplifting and other petty offenses, landing in a Catholic reform school where a kindly nun bought her a guitar and a book of Bob Dylan songs. Finding her voice in music, O’Connor signed her first recording contract at age 18 — shortly after her mother died in a car wreck on the way to Mass.

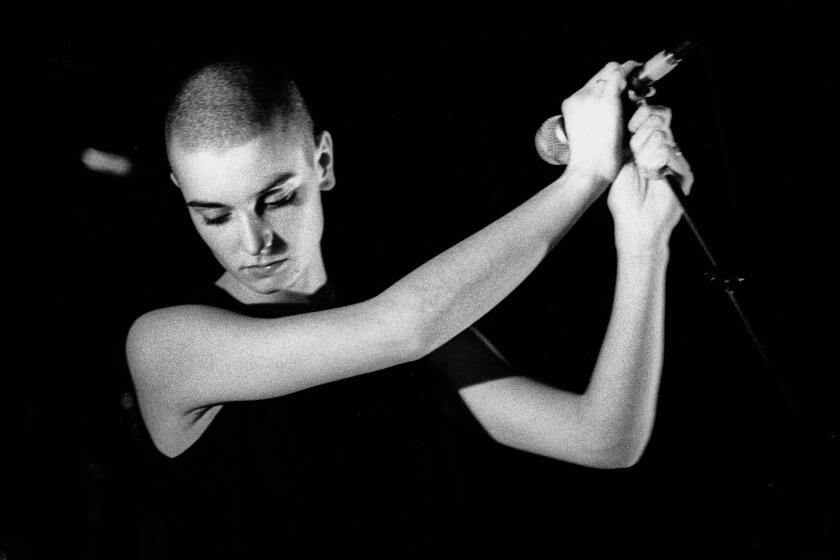

O’Connor wrote her own songs, a musical memoir in progress. One of her first, “Troy,” was a mesmerizing account of love and betrayal. On “Mandinka,” she sings defiantly about not knowing shame or pain. After complaining that the producer assigned to work on her 1987 debut album, “The Lion and the Cobra,” was taking the bite out of her songs, she took over the production herself. Rejecting the record label’s plan to market her as a teen pop queen, O’Connor had her hair shaved off and wore ripped jeans and combat boots. Deeming the photo she wanted for the album cover, where her mouth is open in song, “too angry” for American audiences, label execs swapped in another image, where her eyes are half closed, looking downward, demure.

O’Connor’s music, and message, caught on through college and alternative radio and MTV. Her first public prime-time TV appearance — on the 1989 Grammys, where she was nominated for female rock vocal performance — telegraphed that she was, as Billy Crystal said in his introduction, “no ordinary talent.”

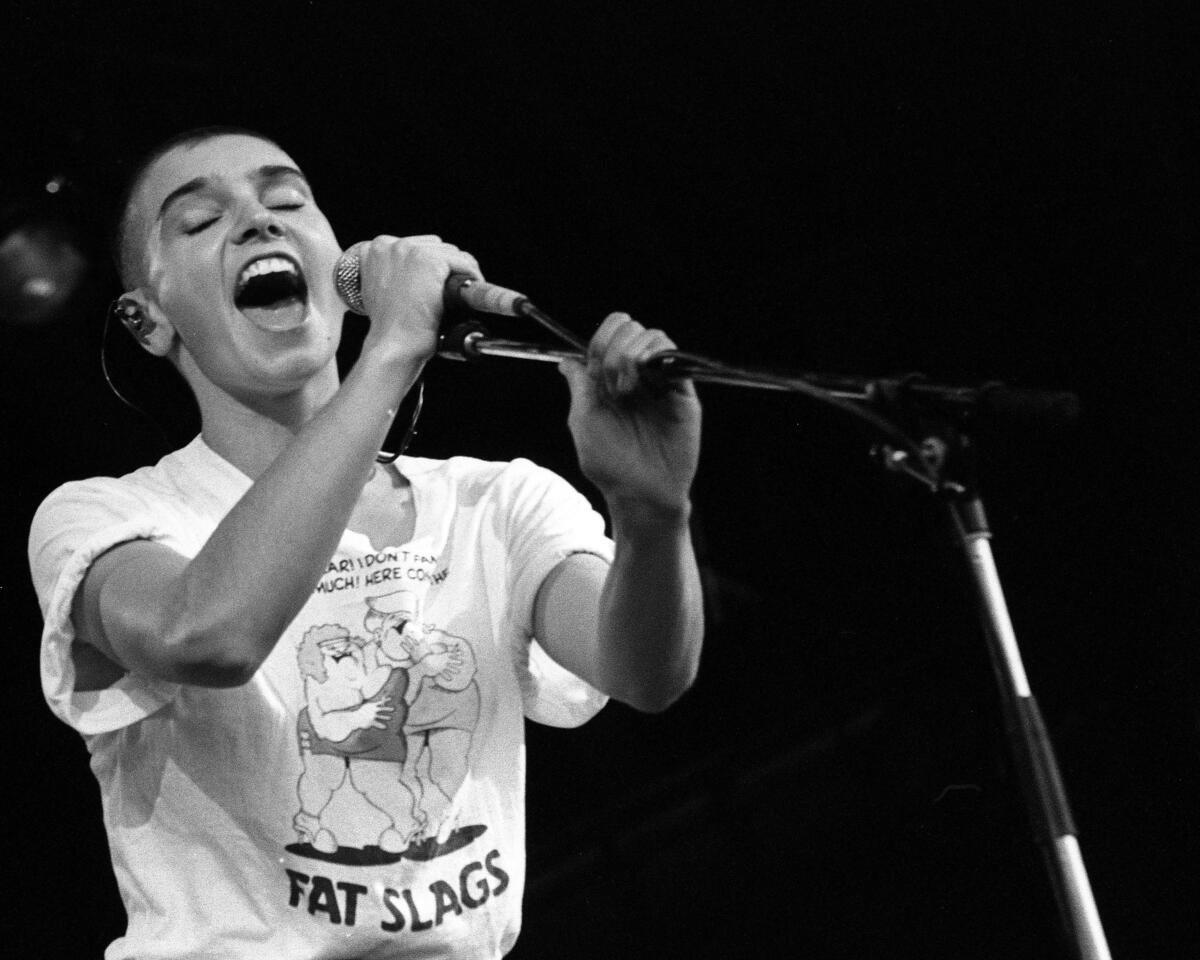

That year, the Recording Academy was to present its first-ever awards for rap music, but citing limited airtime, the presentation would not be televised. In response to being written out of the Grammy telecast, some of the rap nominees boycotted the ceremony. When 21-year old O’Connor came out singing “Mandinka,” she wore Public Enemy’s logo painted in her hair as a badge of solidarity with the artists who had been erased from the program. When she was done, a reporter from The Times said she appeared nervous backstage, as if she somehow knew that she didn’t belong in the pop world, and that her moment was bound not to last.

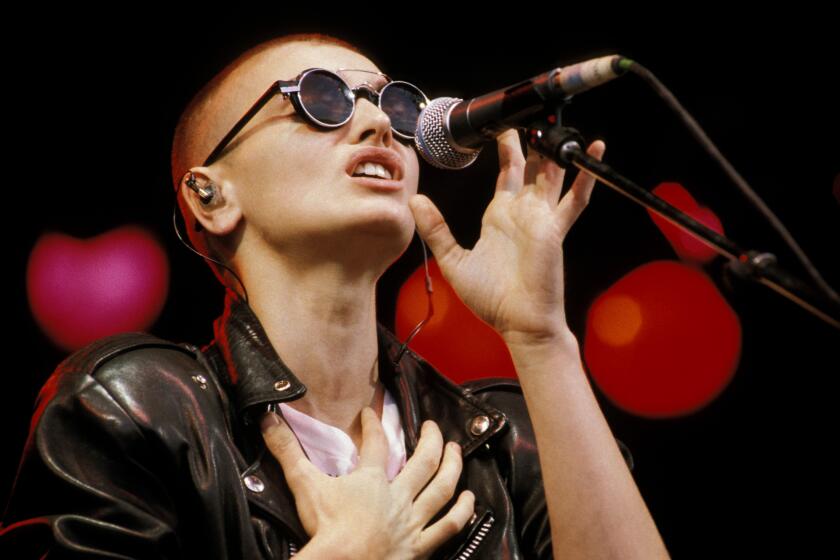

That was OK, because O’Connor saw herself as a protest singer in the vein of Dylan — a point she made clear on her next album, 1990’s “I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got.” While it was the Prince-penned single “Nothing Compares 2 U” that made her a global superstar, she took on racism and police brutality in “Black Boys on Mopeds” and the warped values of the music industry in “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” And, more obliquely, she sang about being an abuse survivor, on the title track and elsewhere.

From that point on, whenever she sat with journalists, she talked about racism, sexism, child abuse and the music industry’s relentless focus on commercial success, though she rarely found a sympathetic ear. She also used awards shows to do the same, until she decided to forgo them altogether — another form of protest.

O’Connor followed the breakout success of “I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got,” which went to No. 1 in multiple countries, with a 1992 collection of show tunes and standards — not exactly a formula for pop success. In the music video for “Success Has Made a Failure of Our Home,” a Loretta Lynn song given a big-band treatment, O’Connor stood at a dais testifying (via sign language) about child abuse. On the wall behind her were the faces of children on slides from Amnesty International — the young victims of war atrocities — while photographers snapped pictures of O’Connor’s testimony, confusing it with entertainment.

A singer of rare power and finesse, O’Connor found fame with a brooding Prince song, then spent decades spanning styles and genres in search of emotional truths.

All of this was the lead-up to her Oct. 3, 1992, appearance on “Saturday Night Live.” The song she sang that night was Bob Marley’s “War,” which was not on her album. She changed some of the song’s lyrics, which addressed racial oppression, to address child abuse. The photo of the pope in fact belonged to her late mother, a souvenir of his 1979 trip to Ireland that had been her prized possession. Destroying the photo was meant to draw attention to the Catholic Church’s pervasive sexual abuse of its young and most vulnerable followers — not to attack the faith or even the pope, but to destroy a symbol of the institution’s hypocrisy as it covered its tracks and silenced survivors.

The retribution was swift and unforgiving. Her albums were steamrollered outside of her label’s offices in Rockefeller Center. On late night TV, O’Connor was turned into a punchline and a punching bag by Joe Pesci, who bragged that he would have “gave her such a smack,” and by Phil Hartman, who joked about tearing up a photo of her supposed lookalike, Uncle Fester from “The Addams Family.” Even Madonna, no stranger to controversy herself, was critical of O’Connor, telling Irish public broadcaster RTE that she thought there was a better way to present her ideas. Within days, O’Connor did just that, releasing an open letter in which she doubled down on her criticism of the church.

“SNL” effectively marked the end of O’Connor’s career as a pop star, but she never stopped making music or speaking out against social injustice, her activism overshadowed by the relentless attention on her personal struggles, including her mental health, which she spoke about openly even though it was often used to discredit her.

O’Connor didn’t always get her point across the way she wanted, and did sometimes purposefully stoke outrage, because that’s what provocateurs do. But unlike her male counterparts, she was never afforded the right to use her voice as she saw fit. Even decades later, she was still routinely asked by journalists if she regretted her actions on “SNL,” sidestepping the question of whether an apology was owed to her.

In 2021, when O’Connor published her memoir “Rememberings,” I interviewed her for NPR’s “Morning Edition.” Despite the way she’d been characterized in the press — let’s just say it plainly, as crazy — she was on time and on point. She answered all of my questions, even the difficult ones, the so-called “triggers” her publicist asked me to avoid. After the interview, she emailed me a few times, not to promote herself, but to share music she discovered by other largely unknown artists that she was excited about.

That radio feature turned out to be the beginning of a much deeper examination into O’Connor, culminating in a book that not only looked into her story, but how that story was a reflection of our culture: the double standards female artists are held to, the misogyny they experience and how our perceptions of them are often filtered through the lens of sexism.

It also led me to reflect on my position within that culture, as a journalist and an abuse survivor myself. It was risky, emotionally and professionally, for me to write about that, but, inspired by O’Connor, I hoped to spark a conversation about who we are as a culture, and what we could be if we listened as easily as we judged.

I don’t know if O’Connor read my book. I didn’t ask her to, and she didn’t owe me that. But I do know that the fans around the world who have reached out to me saw her, rightly, as much more than a one-hit wonder or a lightning rod. By singing and talking about things people often didn’t want to hear, O’Connor made it possible for others to confront their own shame and silencing, and to step toward healing and something that feels like hope.

Allyson McCabe is a music journalist and the author of ”Why Sinéad O’Connor Matters.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.