Seal on the George Clooney connection to ‘Kiss From a Rose’ and why singing it is a ‘minefield’

- Share via

Dressed in a baggy green flight suit, his fingernails painted black, Seal squared himself behind a microphone in a Van Nuys rehearsal studio and bobbed his signature bald head as his five-person band wound its way through the intro of his song “Fast Changes.”

The airy, intricately rhythmic folk-soul tune is hardly the best known track from Seal’s self-titled 1994 LP, which sold 4 million copies in the U.S., earned a Grammy nomination for album of the year and spun off the Hot 100-topping “Kiss From a Rose.” But on a recent afternoon the 60-year-old British singer was prepping for a tour meant to commemorate the three decades since he broke out with his 1991 debut (also titled “Seal”) and its smash follow-up.

Thus the deep cut.

To listen back to Seal’s first two albums, both of which he made with producer Trevor Horn, is of course to marvel at the rough-cut beauty of his voice, with its stylish rasp and its promise of a lover’s tender care. Yet the records also make a prescient argument about the porousness of genre lines as they move among throbbing dance music (“Crazy”), bluesy acoustic rock (“Whirlpool”), luxurious torch-song balladry (“Don’t Cry”) and trippy gospel-funk (“Future Love Paradise”).

From Brill Building-era classics to ‘80s quiet-storm staples, Weil’s songs, many written with husband Barry Mann, became part of the fabric of American life.

For the tour, which stops Wednesday night at the Greek Theatre, Seal reteamed with Horn, 73, who’s serving as the singer’s musical director and who’s opening shows with his ’80s new wave band the Buggles of “Video Killed the Radio Star” fame. (Beyond his work with Seal, Horn is known for producing records by Yes, Pet Shop Boys and Frankie Goes to Hollywood.) The two Brits, who’ve lived in Los Angeles for decades, sat down during a break from rehearsal to discuss their long partnership. These are edited excerpts from the conversation and from a subsequent phone call with Seal.

When did you first visit L.A.?

Seal: In 1990, because Trevor suggested it would be good for me to come to America to meet different musicians. Looking back now, I can see that I was actually quite narrow-minded in terms of what I thought was possible. I had this idea of making a sort of cool, clubby record that all my friends liked but probably wouldn’t sell s—.

Trevor, what was your idea?

Trevor Horn: I was staying in a house in Fryman Canyon — it’s George Clooney’s house now, though it wasn’t then. I’d managed to get a cheap deal for it because the people who owned it couldn’t rent it out. So I took it, and the minute I came in, I pulled all the furniture out and completely freaked out the owners. They showed up: “What are you doing?!” I said, “I’m setting up a studio in your ballroom.”

It was really to work on “Crazy,” wasn’t it? Because you’d worked on the song with Guy Sigsworth and got some really good synth stuff, and then we worked with Tim Simenon and we got the middle drum break. But we didn’t have the record yet. I knew we were going to have to put some serious work into it, and I thought it’d be good for Seal to be here. The funny thing is, when he arrived, I tried a different approach to “Crazy” — I’d done it a bit like Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis. Seal said, “Look at me — do you think I could move to that track?” It was completely wrong. So we slowed it down, did a few things, and in the end we had a great time. Some wonderful moments, 3 o’clock in the morning in the canyon. L.A.’s like that.

Where were you staying, Seal, while Trevor was at Clooney’s future manse?

Horn: You kidding? He had the guest bedroom. We were all there. Then we came back to England. That was a bit of a downer.

Seal: A record sounds like the time you had making it. That’s what I mean about Trevor trying to make my picture bigger and see different possibilities, whether it was the time at George Clooney’s house or hanging out with some babe on Sunset or being picked up at the airport by a limousine that Trevor had sent for me, which was bigger than any f— house I’d ever lived in. It’s all those experiences that actually make the record.

Horn: Seal wanted to make a kind of record that I’d never made before. So I was trying to figure out what it was and how to get it to work because it wasn’t like a rock record. And it wasn’t an R&B record. It had certain things that Seal was insistent on, like the groove. But the songs were all unusual. None of them were like a formula where you have a verse and then a bridge and then a chorus. It was all stuff like “Future Love Paradise.” I’d never heard anything like that before.

What genre can you not sing, Seal?

Seal: If you’re a singer, you just sing. I never look at a genre and go, “Oh, I can’t sing that.”

Country music?

Seal: Oh, I could sing country.

Horn: You’d be great at country. You were just playing me a track the other day .…

Seal: “More of You” by Chris Stapleton, which apparently isn’t traditional country. But we’re English — it sounds country to me.

On your “Soul” and “Soul 2” albums, you’re mostly covering American soul songs. What’s the difference between American soul music and British soul music?

Seal: I don’t think we can quite do it like the Americans. I know they’re not a soul band, but if you look at the Rolling Stones, for example, it’s really clear where the influences come from: Muddy Waters, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, rhythm & blues. Early Beatles too. All they were trying to do is cop what the Americans did. But it never really came out like that. It came out weird.

Horn: Because we’re a bit crap.

Seal: Trevor’s right: We’re a bit crap. Because that type of music, it’s not something that you cop — it’s something that you live. The thing English people had in our favor was we had a lot of what we call neck. We weren’t afraid to have a go. If we were crap, we were wrong and strong.

Horn: Think about how much neck Mick Jagger and Keith Richards have. And they came here too. They went to Chess Studios to record [in 1964] because they wanted to get away from [producer] Norrie Paramor and Abbey Road. That’s why their records sounded better than anybody’s in the ’60s, because they were dirtier.

As she put it night after night singing ‘Proud Mary’: ‘I never lost one minute of sleeping worrying about the way that things might have been.’

The first couple of Seal albums came out amid a flowering of Black British soul music: you, Lisa Stansfield, Soul II Soul. Did you feel aligned with those acts?

Seal: Not so much, though I acknowledge that we were contemporaries for sure.

Horn: They were primarily dance acts.

Seal: Trevor and I were always trying to do something different. I remember banging on about Crosby, Stills & Nash, playing him songs like “Carry On” and telling him that I liked how they weren’t linear. Trevor was like, “Yeah, but there’s no reason we can’t do that.” I don’t take that lightly, because I’ve worked with other producers — good producers — but they were less enthusiastic about embracing harebrained ideas.

Trevor, what did you think of the records Seal made with David Foster?

Horn: I liked the first “Soul” album. Foster’s a good producer. I mean, I did like early Chicago best [before the rock band hired Foster in the early ’80s]. One forgets how muso Chicago was. Once [founding Chicago guitarist] Terry Kath was gone, it all started to change.

Seal: I liked working with Foster, but we were making a record of covers. Eventually, I ended up doing a record of original material with him [2010’s “Commitment”], and that didn’t really work.

Have either of you ever heard anyone do a good cover of “Kiss From a Rose”?

Seal: The guy on YouTube who does the Freddie Mercury stuff [Marc Martel], he does a great one. Well, I say it’s great. He can hit all the notes. “Kiss From a Rose” is a f— minefield.

Horn: I was at an awards thing, and I went to the loo while some bulls— was going on. Elton [John] came out of one of the stalls and said, “I tried singing ‘Kiss From a Rose’ the other day. It’s not an easy song to sing, is it?”

Seal: They’re not the same type of song, but you know when you hear someone try to sing “Kiss” by Prince? It just doesn’t work — like, ever. I’m not by any means the world’s greatest singer, but I have a thing that I do, and “Kiss From a Rose” is a showcase of that. That’s why people tend to come unstuck when they try it.

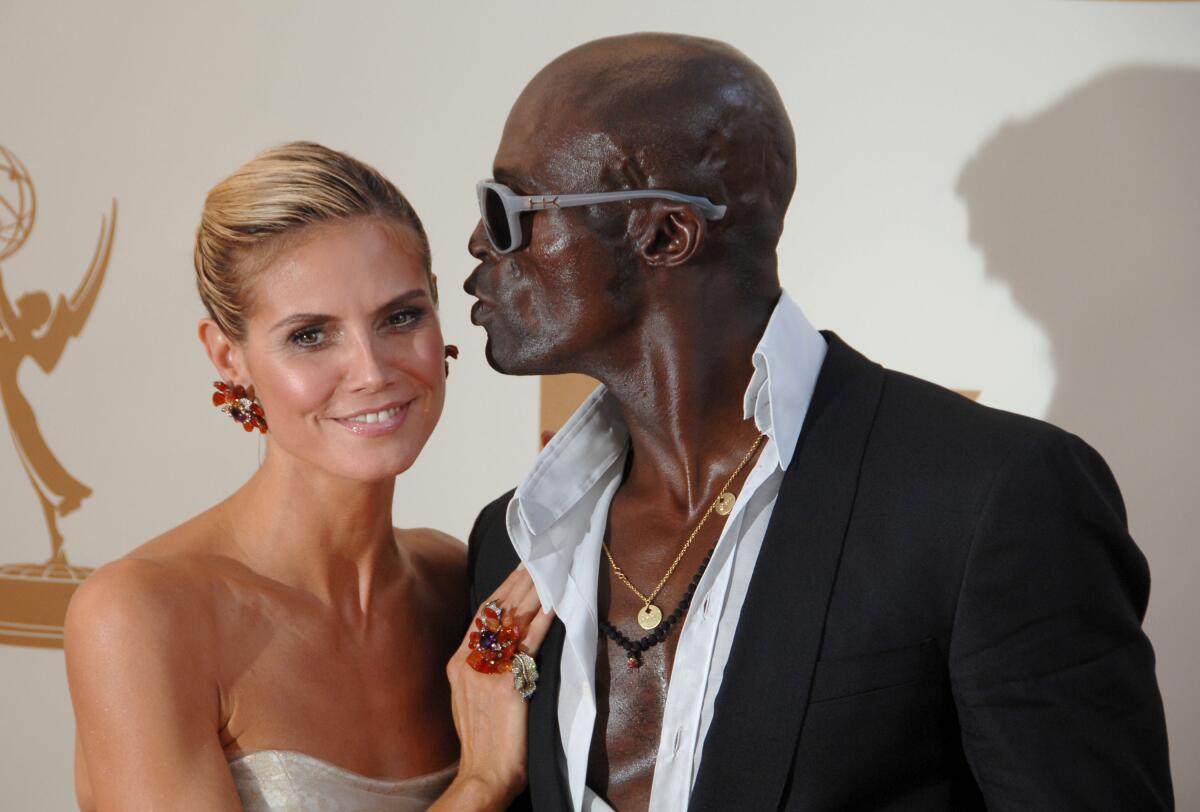

In addition to the platinum records and the Grammys — “Kiss From a Rose” won record of the year and song of the year in 1996 — Seal’s success brought a level of tabloid scrutiny that only increased when he married supermodel and TV host Heidi Klum in 2005. (The couple, who divorced in 2012, share four children.) Today, Seal describes fame as something of a nuisance, though that didn’t stop him from making a memorable cameo as himself in the Lonely Island’s 2016 “Popstar” movie or from competing on “The Masked Singer” in 2019.

You’re naked on the cover of the second Seal album and on the cover of “Human Being” from 1998. Did you think of yourself as a sex symbol?

Seal: Not for one minute. Sure, I understood that how you look and how you present yourself is part and parcel to being a good artist. I have a background in design and a little bit of architecture, and I was a tailor, so I was always very conscious of form. But my reason for being nude on a couple of album covers was to be vulnerable. It wasn’t for any kind of macho reason. I was going through a bunch of stuff — low self-esteem and anxiety — and trying to work that out. I understood that back then the way to liberate myself was to be vulnerable, because once you can do that — once you can let go of all of your armor that we carry around with us — then nothing can really damage you, and therefore you achieve true strength.

But there’s certainly an element of sexuality in your performance.

Seal: Performing is quite a sexual act. You’re trying to get lost and you’re trying to let go, and the lines between that and sex are very, very fine.

How does it feel to be looked at in this phase of your life?

Seal: It never really crosses my mind. Do I feel comfortable? Perhaps more so now. I feel at ease, I guess, as a result of that work that I did earlier on. That was for me — it wasn’t really for anyone else.

You seem quite conscientious of your kids’ proximity to fame. Have you ever tried to steer them away from show business?

Seal: That doesn’t worry me. It’s an interesting life, and there are many advantages that go along with the obvious pitfalls one can succumb to in show business. But I’ve tried to instill in my eldest daughter, Leni, that the word “celebrity” implies that one is famous for being famous, and there’s very little happiness in that. It’s just so tragically empty that I could vomit.

Leni’s in the public eye at the moment [as a model], and I must say that I’m really proud of her — of the way she sees it for what it is. She understands that it’s a means to something else and that being famous will not give you self-worth. But the rest of my kids, they couldn’t give a flying you-know-what about fame. Honestly, they’ve never once exhibited any kind of wow factor about anything I do. They appreciate the fact that I sing, and every now and then they’ll let on that they listen to my music. But mostly they just see me as Dad who’s kind of annoying sometimes.

What else do they listen to?

Seal: They listen to a lot of Queen and a lot of the old classics that you’d be surprised. A lot of trap and mumble rap — their version of punk, which I’m not supposed to understand, let alone like.

Do you feel like you do understand it?

Seal: I understand what it’s doing. It’s anti-establishment, that’s all it is. I don’t think it’s as good as punk was.

You’re at a point now where you can kind of step into the limelight when you want to and then step back out of it. Earlier in your life, the attention seemed unavoidable.

Seal: The difference is that I’m not married to somebody whose career and life is basically founded on that attention. Before I got married, you never really used to see that much of me. There was a certain kind of mystery because I never went out and sought fame. I just happened to be famous. But when I got married, that whole thing became a circus, and I really detested it with every cell and fiber in my body.

Did your detesting it harm your marriage?

Seal: No, because if the two people that are married are in sync in understanding the circus, then it becomes like an instrument that you can play.

Is there anything about the circus that you miss?

Seal: Not a damn thing.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.