How a bluegrass singer overcame all kinds of obstacles to become a top Grammy nominee

- Share via

When it comes to awards shows, Molly Tuttle knows the line about how it’s an honor just to be nominated. What she found out only recently, though, is that the way you’re nominated can be its own reward.

Tuttle, a 30-year-old singer and guitarist widely respected in the world of bluegrass music, is up for two prizes at Sunday’s 65th Grammy Awards: best bluegrass album for her third studio LP, “Crooked Tree,” and best new artist. The first nod she’d long regarded as a goal — “something I’d have to work really hard for,” as she puts it, “but attainable because I’ve had friends who’ve been nominated.”

Best new artist, on the other hand, “was not something I’d even thought was a possibility,” let alone that she’d get the news from one of pop’s biggest young stars.

“That was surreal,” Tuttle says of hearing Olivia Rodrigo, winner of best new artist at the 2022 Grammys, say her name as Rodrigo took part in the Recording Academy’s nominations announcement last fall. With a smile, Tuttle — who has alopecia areata, an incurable autoimmune disease that causes hair loss — adds that she was turned on to Rodrigo by an 11-year-old friend she met through her work with an alopecia foundation.

“So in their eyes this was like — whoa, major cred moment for me.”

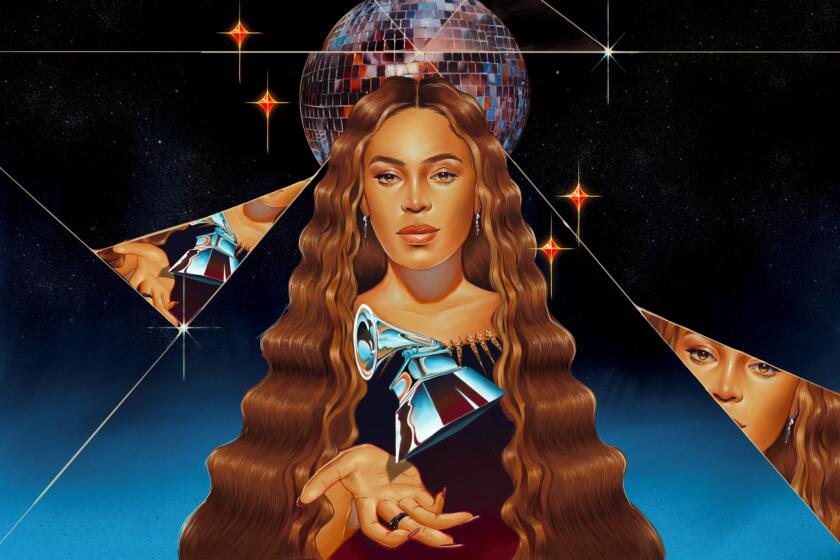

She’s among the most honored artists in Grammy history, but has never won album of the year. Racism? Sexism? Rockism? On Sunday, the Grammys are out of excuses.

Tuttle’s surprise at her best new artist nod was well founded. For the last decade the category has been dominated by highly visible acts with inescapable radio hits: Rodrigo, Megan Thee Stallion, Billie Eilish, Dua Lipa, Meghan Trainor, Sam Smith. Occasionally a musician along Tuttle’s lines — that is, a skilled performer from a relatively specialized field — has made it into the competition, as the folk-jazz singer and composer Arooj Aftab did last year. But you have to go back to 2011, when Esperanza Spalding famously upset both Drake and Justin Bieber, to find the last time such an artist took home the the award.

Could Tuttle be the next? Minus a clear breakout act, this year’s best new artist category — in which the other nine nominees include the R&B singer Muni Long, the rapper Latto, the Brazilian singer Anitta and the rock bands Måneskin (from Italy) and Wet Leg (from the UK’s Isle of Wight) — feels unusually up for grabs; among the longshots are two more gifted specialists: the jazz vocalist Samara Joy and the French-American jazz duo Domi & JD Beck. Given that spread, Grammy experts say it’s possible that Recording Academy members will cast their ballots according to their genre loyalties, in which case Tuttle has no natural competition for the votes of the academy’s sizable Nashville contingent.

“And the Nashville people actually bother to vote,” says one insider, invoking an oft-repeated claim that the academy has trouble persuading members to take part in a voting process that the group’s chief executive, Harvey Mason Jr., has admitted is more tedious than he’d like it to be.

As for Tuttle’s getting on the Grammy ballot in the first place, she made a splash in the awards ecosystem by becoming the first woman to win the International Bluegrass Music Assn.’s prize for guitar player of the year — won it two years in a row, in fact, in 2017 and 2018. “That was huge,” says Jerry Douglas, the veteran dobro player who produced “Crooked Tree” and has played for years with Alison Krauss. “The old women-can’t-play thing, that’s gone.”

Tuttle is signed to Nonesuch Records, the prestigious label home to Grammy faves such as Emmylou Harris (who has 47 career nominations) and the Black Keys (who have 13); she appeared not long ago on “CBS Saturday Morning,” a reliable path to exposure among older Grammy voters. And she’s put in time meeting folks in Nashville, where she moved in 2015 after growing up in Palo Alto.

“People like to vote for people they know,” says Tuttle’s well-connected manager, Ken Levitan — a truism born out over the last few years by Brandi Carlile, who’s openly acknowledged the value of playing the right galas and shaking the right hands. (Both Tuttle and Carlile are set to perform at Friday night’s MusiCares Persons of the Year tribute to Smokey Robinson and Motown founder Berry Gordy.)

With Beyoncé leading the pack with nine nominations, the Grammy Awards return to L.A. this Sunday. Here’s everything to know about the ceremony.

Of course, none of the politicking would mean much if Tuttle — who just released a spirited cover of Rodrigo’s “Good 4 U” as part of a Spotify best new artist promotion — weren’t the exceptional musician she proves herself to be on “Crooked Tree,” which deploys her ultra-fast picking and her high, sturdy vocals in songs about love, family and small-minded gender roles; there’s even one about the gentrification of her native Bay Area. Grammy voters adore what you might call a young fogey — someone in their 20s or 30s (like Norah Jones in 2003) working in a time-honored tradition.

“But Molly’s more than an old soul,” Douglas says. “She writes really mindful songs about topics that we can all get a hold of — not just, like, ‘My little blue pond down by the lake … .’ It’s stuff you gotta think about, stuff that can jar you into reality.”

Tuttle learned to play guitar and banjo from her dad, who’d learned from his dad as a kid living on a farm in Illinois. Her talent was clear from the get-go, though she wasn’t exactly burning to showcase her banjo skills in front of her schoolmates. “That did not seem cool,” she says with a laugh over coffee one recent afternoon before taping a performance on “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” “I felt kind of ashamed by it.”

Alopecia, which she was diagnosed with when she was 3, didn’t help.

“I was always nervous about it,” she says of the disease. “Other kids would be like, ‘What’s with your hair? Why do you always wear a hat?’ And I just wouldn’t know what to say.”

After attending a public elementary school, Tuttle went to a private middle school because her mom was afraid she’d get bullied at the public school, which didn’t allow hats. “And I wasn’t comfortable wearing a wig yet or going without a hat.” The private school was “a total hippie place — the teachers swore, people were barefoot, you called teachers by their first names,” she says. “But we had a cool music teacher who taught me electric guitar.”

Soon she was learning songs by Rancid and Rage Against the Machine to go with the Bill Monroe tunes she’d absorbed at home. “And then Mumford & Sons came out and they had a banjo. I was like, ‘OK, this is getting kind of cool.’”

Indeed, Tuttle’s trip to the Grammys — as well as the ascent of fellow bluegrass musician Billy Strings, who appears on “Crooked Tree” and who’s set to tour arenas this year — aligns with an every-decade-or-so resurgence of old-timey roots music. Think of Mumford, whose “Babel” won album of the year in 2013; think of the soundtrack from “O Brother, Where Art Thou?,” which took the same prize in 2002; think of Krauss, who won the first of her 27 Grammys in 1991.

Douglas has a theory that bluegrass makes mainstream inroads in times of political turmoil, beginning with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” during the Vietnam War. “And ‘O Brother,’ that all happened around 9/11,” he says. “At those moments people want something honest.”

Beyoncé, Adele, Taylor Swift and Harry Styles are among the glittery nominees for the top prizes, but upsets may abound.

After high school, Tuttle studied for two years at Berklee College of Music in Boston — Spalding is also an alum — before heading to Nashville. Asked about going from the coasts to the heartland in the red-state/blue-state era, she says, “I think I was expecting it to feel more comfortable than it did. I’d moved to Boston and that wasn’t a huge adjustment. But Nashville was like, Whoa.” She laughs. “Just the little things that grated on me, like the fact that they don’t do glass recycling and you can’t drive in any direction for 30 minutes without seeing an anti-abortion billboard or a gun billboard. To some extent it still doesn’t feel comfortable to me. But I feel like I found my little place.”

Tuttle will spend much of this year on the road playing headlining shows and festivals including Bonnaroo and opening gigs for Old Crow Medicine Show, with whose Ketch Secor she’s in a romantic relationship. She’s also working on a new album with Douglas that has one song she describes as “like a bluegrass ‘Alice in Wonderland’” and another that “touches on some subjects that won’t make everybody happy,” as Douglas puts it with audible pride.

She’s hoping to reach listeners deeply attuned to the history of bluegrass music as well as folks who know nothing about it.

“Sometimes I’ll be talking to an Uber driver and I’ll tell them I play bluegrass and they’ll say, ‘What, like ‘Beverly Hillbillies’?” Tuttle says. “You just have to give people a different idea.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.