50 years ago, the Wattstax concert made, and even changed, L.A. history

- Share via

The summer of 1972 was a decisive time for Raymond Shields. He’d just graduated from high school and was about to leave Los Angeles behind to study at Northwestern University. It was a summer of house parties and trips to Disneyland, and right at the end, he and a friend bought $1 tickets for the huge musical event called Wattstax.

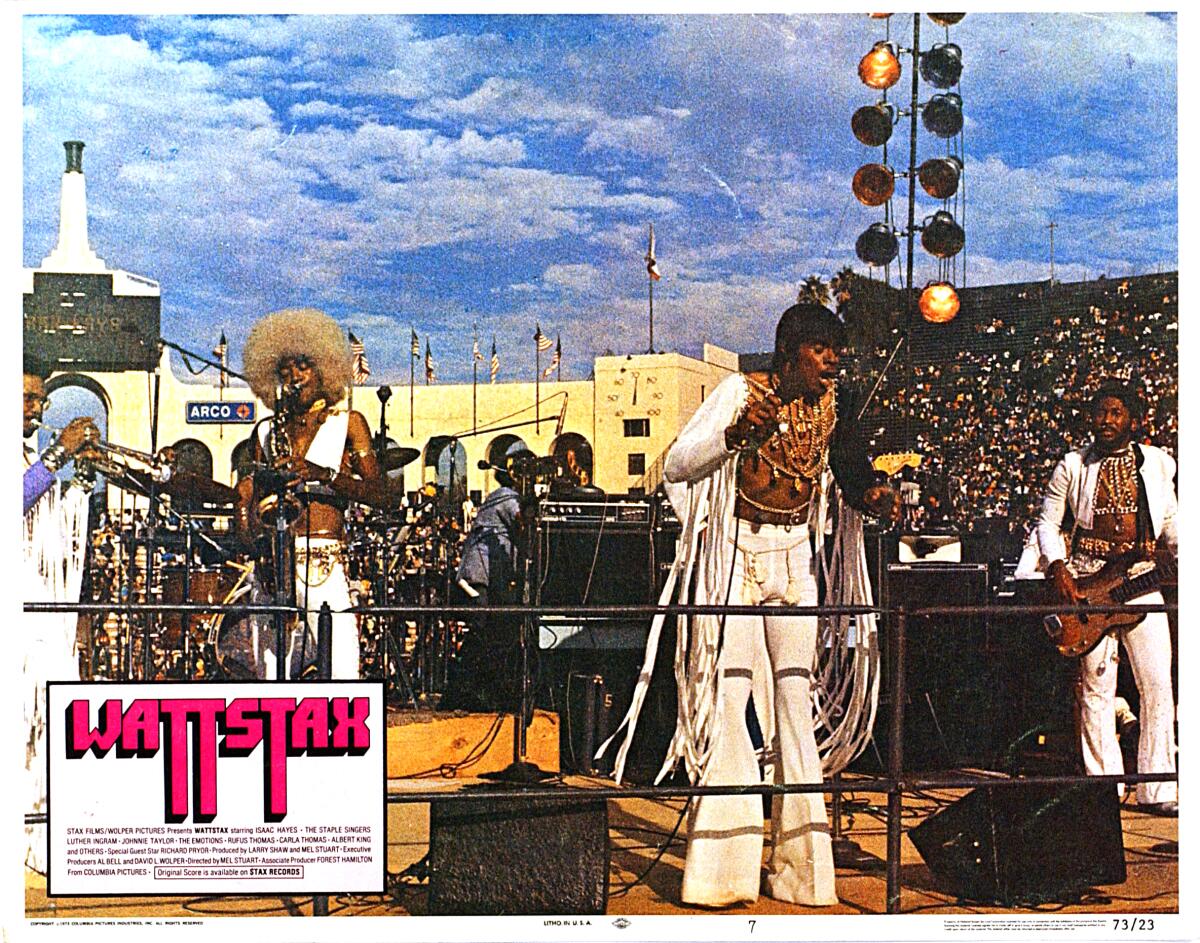

A daylong festival 50 years ago on Aug. 20 at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, Wattstax was intended as a Black Woodstock. But the name of course was also a reference to the Watts Uprising of 1965, when the arrest of a Black motorist led to six days of conflict, during which 34 people died. Shields remembers those days in August 1965, “the strangest kind of time” when he saw Jeeps loaded with National Guardsmen rolling past his home, .30 caliber machine guns swinging back and forth, gunners looking for a target.

The name Wattstax was also a reference to the famed Memphis-based Stax record label, which would provide the talent for the day. Shields was among the more than 85,000 fans at the Coliseum to see soul music stars like Isaac Hayes and the Staple Singers and the heavy funk of the Bar-Kays, and to soak up the message of empowerment and pride from a young Rev. Jesse Jackson, community activist Tommy Jacquette and others.

On Friday, the Los Angeles City Council and Mayor Eric Garcetti issued a joint proclamation, declaring Aug. 20, 2022, “Wattstax Day.” Memory fades, but certain details remain indelible to Shields, like seeing the Lockers, the street dance crew from Los Angeles, staking out the periphery of the crowd and popping and locking all day long to the music in their giant hats and striped socks. Like soul singer Rufus Thomas, performing in pink hot pants. “He had a hit song, ‘The Funky Chicken,’ and everybody in the stadium was doing the Funky Chicken, over 100,000 standing up simultaneously doing the dance. He did it too, in his cape and his pink hot pants,” Shields chuckled.

“That was the big event of the year,” he recalled last week, “coming with a lot of hope and positive energy. Everybody wanted to see it.”

In the wake of the 1965 Uprising, the community most affected experienced a creative rebirth. Institutions like the Watts Happening Coffee House, the Studio Watts Workshop, the Watts Repertory Theater and the Watts Writers Workshop pointed the way to new theater, jazz, poetry and more. The still-ongoing Watts Summer Festival was also born in the ashes of 1965, founded by Jacquette and others, showcasing visual art, music, crafts and more each summer in Will Rogers Park (now called Ted Watkins Memorial Park).

The rest of the city mostly looked away. A young entrepreneur from South Los Angeles named Forest Hamilton was booking shows around town and advising acts like Charles Wright and the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band and Bill Withers. His father was jazz drummer Chico Hamilton, his uncle actor Bernie Hamilton.

William A. Burke, businessman, philanthropist and founder of the Los Angeles Marathon, was a friend of Hamilton’s (who died in 2000). Burke remembered the Christmas when Hamilton, still in high school, called to tell him his dad and mom left a note and keys on the kitchen table, abruptly announcing they had moved to New York City. “Hey man, ain’t that a bitch!” said Burke. “Either you become independent or you die. Forest’s whole life was made up of moments like that and he just kept on moving.”

People liked Hamilton “because he was big like a teddy bear,” said Burke. Al Bell, co-owner of Stax Records, liked Hamilton enough to make him the label’s West Coast point man in the early 1970s. Bell wanted to get Stax into the movies, and Hamilton sent Richard Dedeaux, a poet with the group the Watts Prophets, to Memphis in the hope that Dedeaux would write a screenplay for a film starring Isaac Hayes. The radical proto-raps of the Prophets came out of the Watts renaissance and had been showcased at the Summer Festival.

Live Nation has been repeatedly accused of failing to follow industry protocols for keeping concertgoers and performers safe, according to a Times review.

Hamilton never got Hayes his film debut, but he got Stax theirs. First, he sold Bell on sending a couple of his artists west to the 1972 Watts Summer Festival, a plan that ramped up when Hayes said he wanted to be involved. The idea grew into a Woodstock-like showcase at the Coliseum — Wattstock, they first were going to call it — and that grew into an event that would speak to the entire social moment with the participation of Jacquette and Jackson, Black film icons Melvin Van Peebles and Richard Roundtree as well as many of the soul stars who had built Stax.

Down the hall from Hamilton’s office on Wilshire Boulevard was an aspiring mogul named David Wolper, and through Wolper Stax hired director Mel Stuart, who had just made “Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory,” to film the event.

Stax had lost control of its catalog in the late 1960s and rebuilt itself from scratch. By then Otis Redding had died and Booker T. had left the label, as had guitarist Steve Cropper. The label was back to making hits but also eager to extend its name beyond music, aiming for the footprint that rival Motown Records had in Hollywood, and investing in Broadway productions. Wattstax was, besides everything else, an act of smart brand management. And when the success of Wattstax, in the words of Stax historian Robert Gordon, made the label “a household name,” it led to a distribution deal with CBS. In short, Wattstax aimed to reach an audience far from Watts.

“Listen, success has many fathers. Failure is an orphan,” said Burke. “Everybody took credit for Wattstax. But I can tell you for a fact … nobody, nobody wanted to do Wattstax. Forest was just dog-ass about it.” He got corporate backing from Schlitz beer and persuaded local Black radio to talk it up.

“It wasn’t about the money — the artists probably didn’t make any from Wattstax,” said Burke. “They came because it was a signature moment for Black people.”

Wattstax was intended as a display of culture and autonomy, and to raise money for the Summer Festival and other local institutions. It hit an emotional chord from the start and resonated for the next six hours. Singer Kim Weston performed the “Star Spangled Banner,” which, in the year of Watergate and less than a year after Attica boiled over, and at a time when disinvestment had gutted South Los Angeles, did not play as it would have at Dodger Stadium.

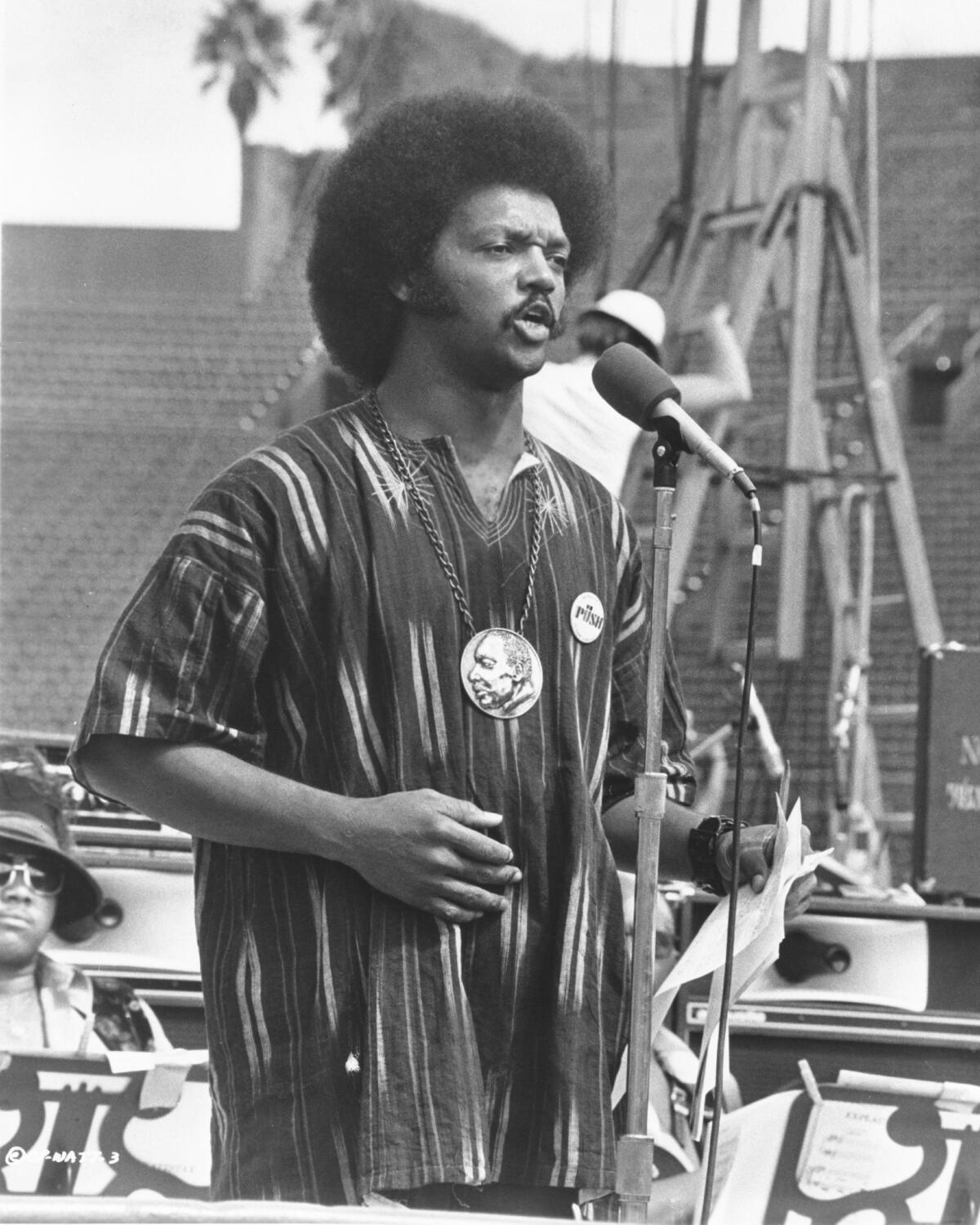

Onto the stage came Jesse Jackson, whose just-founded Operation PUSH was applying pressure on corporations to finance change. His speech was powerfully interactive, a call-and-response that had the Coliseum answering his “What time is it?” with shouts of “Nation time!”

Then Weston, a magnificent singer who had previously recorded for Motown, performed “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” known as “the Black national anthem,” and the whole stadium was singing along, fists in the air.

Moments like that came out of careful planning sessions at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel attended by Bell, Jackson, a young Clarence Avant, Hamilton and others. Bell was the decision maker.

“That day was a Wattstax Civic League meeting,” Bell, now 82, enthuses on the phone from his Arkansas home. “You had hopelessness in the mind and hearts of people sitting there in that Los Angeles Coliseum — their people were being killed, murdered, lynched, disrespected. They didn’t have a positive association with the national anthem. But they did when that Black national anthem came on.

“It was a highlight in all of our lives as African American citizens. We compassionately and proudly exclaimed, ‘I am somebody.’ ”

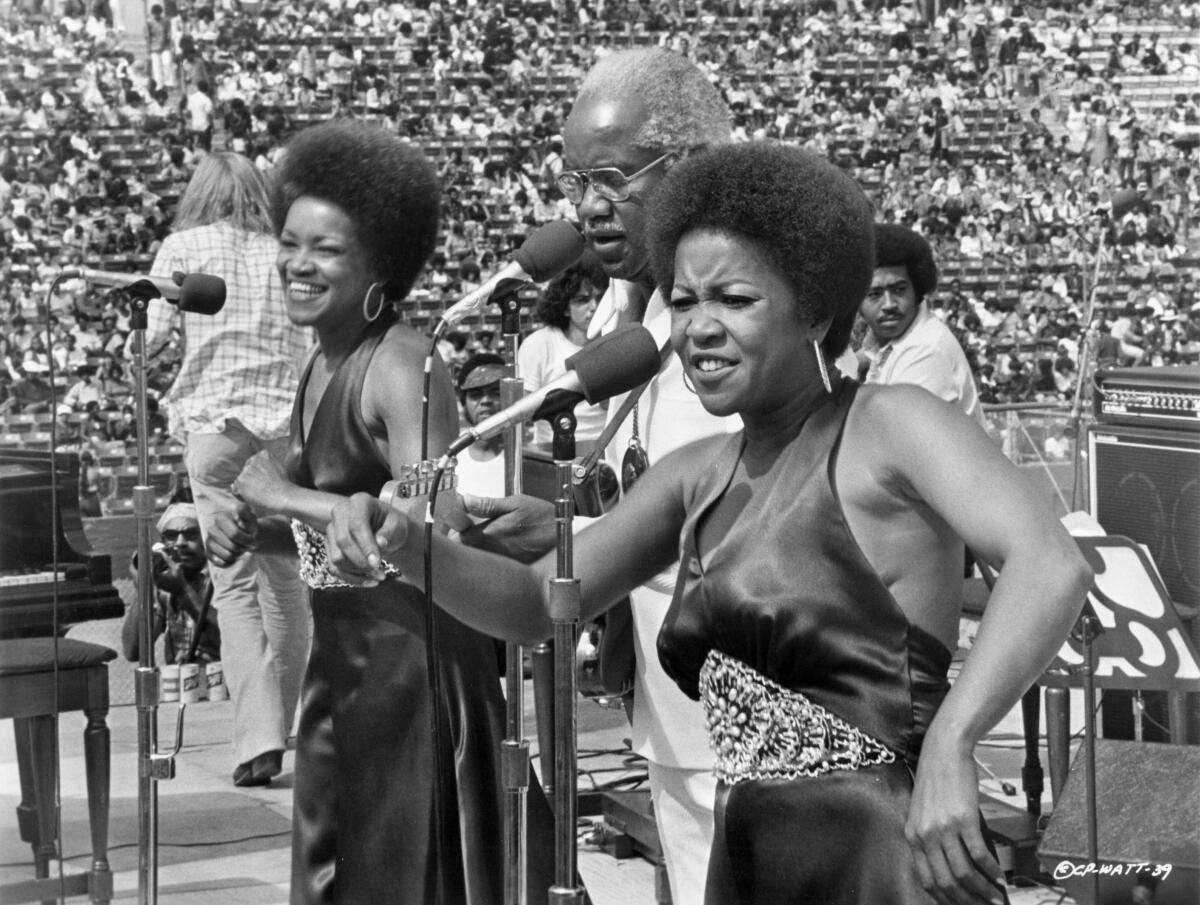

Shortly, the Staple Singers were performing “Respect Yourself” and “The Things I Like About Me,” which extended Jackson’s message in all directions.

Some 26 acts hit the two stages set up on the football field that afternoon, and legend has it way more than that were ready to go on. The great songwriter and singer William Bell (no relation to Al Bell) remembers the long runway to the stage, wire mesh barely keeping the crowd back, and how he had to race a block and a half from the dressing room to the stage, so vast was the Coliseum. And when he peeked out, it was “both frightening and exhilarating, that many people listening to a show that we were very proud of.” Bell sang his aching ballad “I Forgot to Be Your Lover,” participated in a gospel number and emceed throughout the day. All of it, he says with amazement, whipping by as if it was just a minute.

The Southern stars were in town, Eddie Floyd singing “Knock on Wood,” Carla Thomas performing “Gee Whiz” and “B-A-B-Y.” But it was an even better day, just maybe, for lesser-known acts who seized the moment, like Bishop Rance Allen, a guitar-playing prophet from Michigan whose soul-stirring group turned his “Lying on the Truth” into a sermon as profound as any heard at Wattstax.

Memphis group the Bar-Kays had already played L.A. several times and, according to bassist James Alexander, had visited the costume shops on Santa Monica Boulevard in order to make an Afrofuturist, Wild West Hollywood entrance. “We wanted to rent some horses, white horses, and when they introduced us we were going to ride in on chariots,” Alexander said. “That’s how we would make our grand entrance.”

But the concerns of the Coliseum grounds crew and of headliner Isaac Hayes (he didn’t want to be upstaged) denied them their chance. Still, the Bar-Kays dressed divinely, channeling their feelings into a four-song set pointing the way to the funk of tomorrow. “Here we were, little country bumpkins from south Memphis in front of 100,000 people, and we actually stole the show!” Alexander crows.

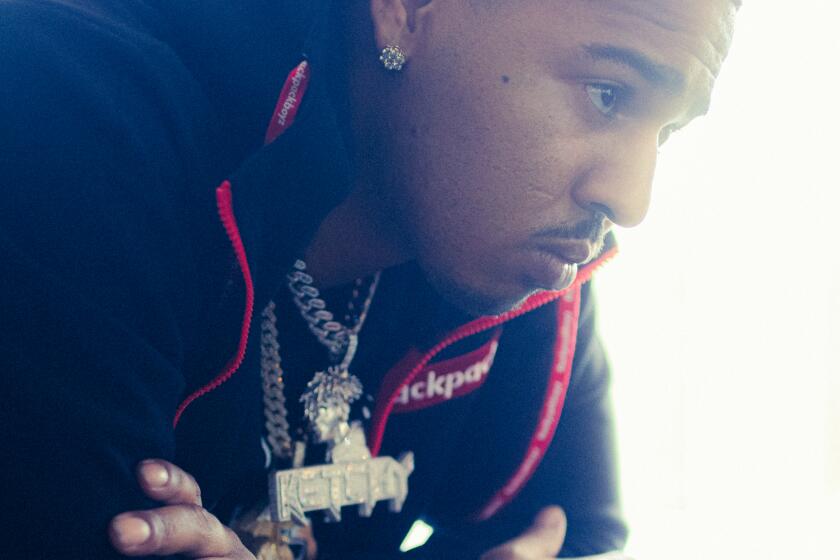

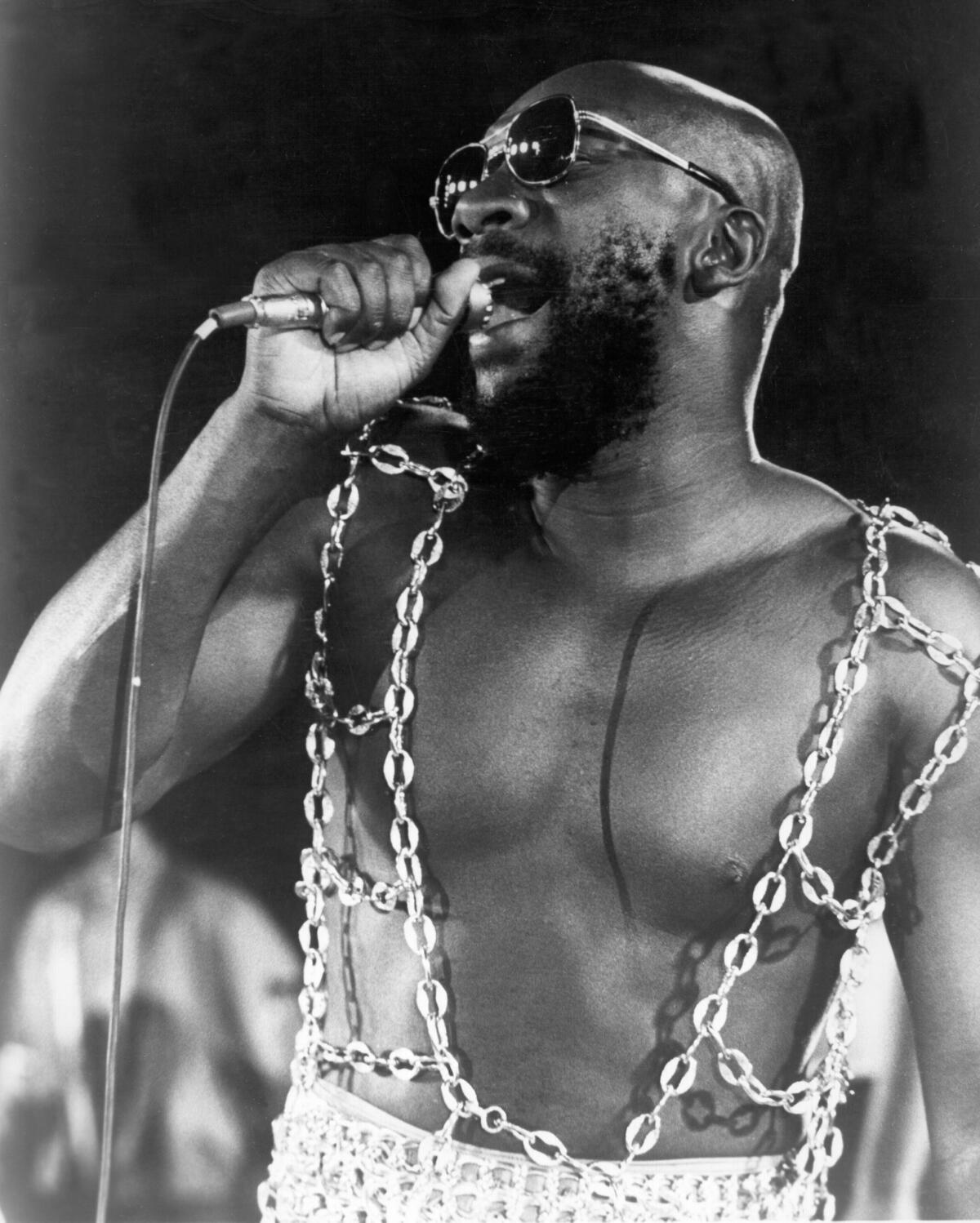

Hayes had reached a career peak. His album “Hot Buttered Soul’s” slow roll, its intimate, symphonic plainspeak, changed soul music in 1969, and in 1971 his “Theme From Shaft” risked dwarfing the film it was made for, so fully did Hayes inhabit a new kind of Black leading man. At Wattstax he made a grand entrance, the “Black Moses” driven to the stage in a golden station wagon and introduced by Jesse Jackson.

But perhaps the most famous moment of the day happened about an hour earlier, when Rufus Thomas arrived. Thomas was 55 in 1972, a vaudevillian in the 1930s who had tap-danced and emceed his way to modest success. But in 1972, it became clear, he was a master of time, leading an itchy, emphatic band, and moving with the kind of delayed-knowingness that owned the moment. He drove the crowd crazy in his white go-go boots and pink hot pants, and if you watch them react in the filmed “Wattstax,” you can see an overflow of great Black dance styles being invented on the spot.

Hundreds of youths flooded the lawn in front of Thomas, a barrier zone until then. It was a testing moment — Bell and Hamilton had an agreement with the city to keep law enforcement outside the Coliseum (in some accounts, the promise was that white officers would stay outside), and crowd control fell to forces assembled by Van Peebles and Stax’s security officer, Johnny Baylor. That plan was now sorely tested as kids romped across the football field. A PR disaster was unfolding, or something worse, Bell feared.

But Thomas had seen it all and used all his talents that day to handle the scene, making it seem like this was nothing worse than a bead of sweat rolling off of Hayes’ dome.

Terry Manning, Stax’s music supervisor for the show and film, was standing in front of Thomas’ stage when he saw hundreds of fans racing toward him.

“It was a little scary,” he says. “When you see a lot of people rushing toward you, you just don’t know. But Rufus had a presence to him, almost like a magician; he could read a crowd and know what he had to do. There was a mysticism to him that took over.”

In February 1973, Columbia Pictures released “Wattstax” as a concert film, following the smash success of 1970’s “Woodstock” documentary. If Questlove’s recent Oscar-winning “Summer of Soul” documentary seamlessly took footage of six different events over several months in 1969 and left you thinking you were sitting on a blanket watching the best concert of your life, Wattstax feels like several competing films.

There’s musical footage; there’s far grimmer commentary from people on the street; and there’s Richard Pryor monologuing into the camera. Then a rising but little-known nightclub comic and TV writer, Pryor’s running commentary on life in Watts and in Black America introduced him to a larger audience.

With its many pieces, “Wattstax” the film felt both kaleidoscopic and incomplete. Still, it was nominated for a Golden Globe for best documentary in 1974, and in 2020 it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress.

Even in its own time, the Wattstax concert had important critics. In his remarkable video “Remnants of the Watts Festival,” made in 1972 and 1973 and available on the Criterion Channel, video and performance artist Ulysses Jenkins recorded scenes from the Summer Festival of 1972. The video features fascinating debates about community control of the culture it produces and corporate sponsorship, and it never mentions the biggest feature of the Watts Festival that year: Wattstax. Instead Jenkins shows a painted portrait of Isaac Hayes hanging in a community exhibition space in Will Rogers Park. He videotapes the annual Festival parade, in which Hayes appeared. But when he asks a group of kids where the star is, they shout back, “Isaac Hayes been gone, he been gone, man.” If corporate money and celebrities were hoped-for saviors of the community, even at the time that already seemed unlikely.

Today, writer and UCLA historian Robin D.G. Kelley notes both the mood in the Coliseum and the mood outside it. Wattstax, he believes, captures “a fairly politicized Black working-class community that managed to transform the Coliseum into a symbol of Black nationalist pride, a carnivalesque space of bodily and sexual freedom, political and social power, artistry.” But then he notes those accompanying interviews, in which “you catch a glimpse of the devastating impact of disinvestment in South L.A. and can anticipate what the next decade (1980s) will bring.”

The creative rebirth in Watts didn’t end in 1972, but its energy moved to Leimert Park, where it flourished until about 10 years ago, says Kelley, though the World Stage carries it forward still. “Gentrification in this sense has done as much damage as the police,” he says. “And yet, where did Black Lives Matter L.A. have its first protest? Leimert Park.”

Kelley points to the work of activist artist Lauren Halsey, including her Summaeverythang community center in South Central, calling it the heart of a new cultural renaissance in Los Angeles. There is the Strategy & Soul center for organizing on Martin Luther King Boulevard near Leimert Park; the work of Erin Christovale, curator, Afrofuturism theorist and co-founder of Black Radical Imagination; the explorations of and interventions in “Street Dance Activism” by Shamell Bell. “These are all engaged, radically disruptive art projects with strong links to community,” notes Kelley, “and they are being replicated all over the country. They’re just not so visible.”

William Bell is 83 today and the Wattstax performer has a new single coming out Aug. 26. He puts the accomplishment of the concert this way: “There was an affirmation that yes, we can maybe make a difference and things can get better. And, for a while, things did get better.” But he notes the killings of unarmed Black men by police in recent times, and the creation of Black Lives Matter.

“Oppressed people, you push them to the wall and they’re gonna fight back.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.