Cypress Hill celebrates 4/20 with a career-spanning documentary. And weed. Lots of weed

- Share via

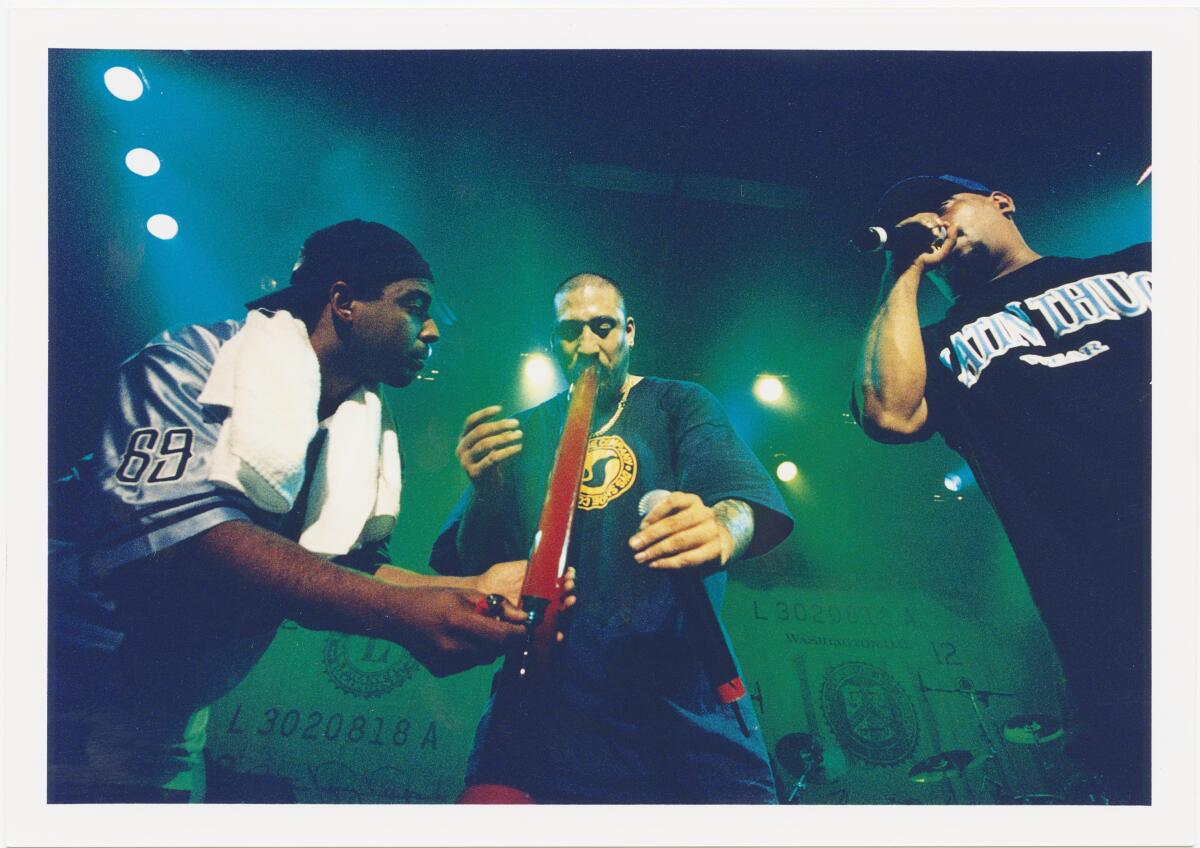

Though Estevan Oriol has never been a member of Cypress Hill, the photographer and filmmaker traveled with the band for most of its 30-plus years. If co-founder B-Real did an onstage hit from the bong Excalibur, Oriol absorbed the cloud of secondhand smoke as his video camera documented the exhalation.

“He was there with us since the late ’80s,” says Cypress Hill’s Sen Dog, 56, sitting opposite Oriol and flanked on either side by fellow members DJ Muggs, B-Real and Eric “Bobo” Correa in their studio compound just south of downtown. Oriol, continues Sen Dog (born Senen Reyes), has worn “many different hats for us, not just tour manager. He was a DJ. He was the therapist — the guy to go to when your head was messed up.”

During a late-morning interview that produced wafts of top-shelf weed smoke, members of the essential L.A. hip-hop group were discussing the new Showtime documentary “Cypress Hill: Insane in the Brain.”

Directed by Oriol using a trove of video footage and photographs from throughout the group’s well-traveled career, “Cypress Hill: Insane in the Brain” premieres Wednesday as part of Showtime’s series of documentaries celebrating the 50th anniversary of hip-hop. Produced by Mass Appeal, a media company co-founded by rapper Nas, the film arrives alongside documentaries about former Bronx gang leader Lorine Padilla and Bushwick Bill of Houston rap group the Geto Boys.

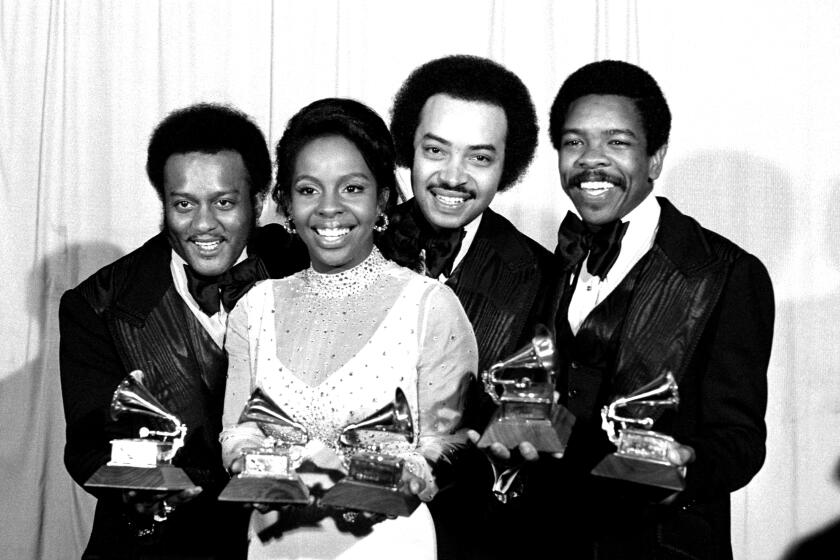

In her new musical memoir, Danyel Smith plumbs the underappreciated genius of Gladys Knight, and her group’s forlorn masterpiece, ‘Midnight Train to Georgia.’

That this insiders’ account of Cypress Hill arrives on April 20, cannabis culture’s high holy day, shouldn’t come as a surprise. Since their formation in the early 1990s, members of Cypress Hill have regularly infused tracks with rhymed odes to THC, gangsta-driven boasts about moving pounds of product and barb-tongued protests against harsh drug sentencing.

The film is part of a busy 2022 for Cypress Hill. In March, the group released its 10th studio album, “Back in Black.” Issued three decades after its self-titled debut and its multi-platinum 1993 follow-up, “Black Sunday,” propelled the South Gate group onto the charts through hits including “How I Could Just Kill a Man,” “Hits From the Bong” and “Insane in the Brain,” the new album is a compact 10-song invective. Combined with Oriol’s documentary and a return to touring, Cypress Hill is entering its fourth decade by celebrating its legacy as Los Angeles’ most enduring rap group.

Sen Dog immigrated to South Gate from Cuba with his brother Sergio — who raps as Mellow Man Ace — and their parents when the kids were in grade school. The Queens-born Muggs relocated to Bell Gardens when he was 14. (“I was not happy about it,” he told one interviewer.) L.A.-born B-Real is the son of a Cuban dad and a Mexican mom. And Bobo is the son of the great Spanish Harlem percussionist Willie “Bobo” Correa. Bobo was raised onstage — one clip in the documentary shows him as a preteen playing with his dad at the Hollywood Bowl.

“We’ve been talking about this documentary since we’ve been on tour in the ’90s,” Oriol says. “We always were shooting. Muggs, Bobo, me and B all had video cameras, so we were filming the shows.” He adds, “We got it to the point where we had 25 years of footage and 25 years of photos.”

Along the way, the group’s members have become music’s most prominent cannabis ambassadors this side of Bob Marley. Where other acts discreetly share pre-gig backstage joints, Cypress Hill has long blazed banana-boat-size spliffs onstage during sets — whether or not local laws allowed it. Flouting authorities at every stop, Cypress Hill has helped define contemporary L.A. cannabis culture, much like the Beach Boys did for surfing and orange crate artists did for the Southern California tourism industry.

This is a group that used to invite the late cannabis activist, author and sativa strain namesake Jack Herer to open its raucous concerts with a lecture on the plant’s benefits and produced a successful traveling weed and music festival called the Cypress Hill Smoke Out. In 2010, the Smoke Out made history when it became the first-ever festival to allow licensed patients to bring and consume cannabis on site.

“Jack Herer was huge to us,” says B-Real, 51. “He opened our eyes to a lot of stuff we weren’t looking at and flooded us with information from his book ‘The Emperor Wears No Clothes.’ It may not look like it, but we all read, so we ripped through that book. That was our bible for a while.”

Did they take jumbo tokes of clownishly large doobies along they way? Absolutely and unapologetically. But as they were exhaling they were also successfully advancing a belief system that’s come to be accepted by Americans across the political spectrum.

“In the course of our run, we realized that Cypress Hill is bigger than us,” says B-Real, born Louis Freese. “People were f— with us in a different way that has had nothing to do with us putting out music. We’re mixing music with advocacy and activism.”

Fans and artists were thrilled to be back at the nation’s preeminent music festival, despite (or because of) the lack of COVID safety protocols.

The rapper, who hosts a raucous weed- and rap-focused podcast called “Dr. Greenthumb” with Bobo as a regular, keeps a kind of joint humidor in the Cypress Hill compound and owns successful cannabis brand Dr. Greenthumb, named for a Cypress Hill song. He hands out joints like they’re business cards. Each is as precisely rolled as a Gitanes and tipped with a glass filter bearing the Greenthumb logo: a caricature of an afro- and sunglasses-wearing B-Real.

B-Real says that the loosening of cannabis laws and the proliferation of product offers “another opportunity for us outside of music.” Despite already owning his own brand, he adds, “I believe when we actually put it together and create the business of Cypress Hill in the cannabis industry — which we haven’t really officially done yet — that’s going to make a big impact.” He calls the project “probably one of the next things we’re going to do.” Directing his attention to his bandmates, he adds with a smile, “I’m manifesting right now, guys. I’m manifesting.”

The recurrent image of Cypress Hill lost in a haze of THC masks a musical legacy dense with innovative, bracing sounds and snapshots of a city on the cusp of breakdown. The opening couplet on its 1991 debut album takes unobstructed aim at the LAPD: “This pig harassed the whole neighborhood / Well this pig worked at the station / This pig he killed my homeboy / So the f— pig went on a vacation.” B-Real does so over a DJ Muggs-produced beat that’s driven by an electric guitar lick and a boom-boom-bap rhythm.

“Cypress Hill: Insane in the Brain” executive producer and Mass Appeal creative director Sacha Jenkins described the group by email as “homies who came together under tough circumstances to express themselves simply because if they didn’t let it out … they would have imploded. Instead, B-Real, Sen Dog, DJ Muggs and Bobo said, ‘You know what? Let’s put some fat beats under that PTSD and let’s rock out.’ Next thing you know, 16-year-olds in Düsseldorf are screaming, ‘How I could just kill a man!’”

Oriol’s film follows this evolution while providing a context for their ascent — and sharing a little bit of his own story. It’s one so compelling that it’s the subject of the 2020 Netflix documentary “LA Originals,” which Oriol directed. Alongside tattoo artist Mister Cartoon, Oriol’s narrative helped drive a “story of two Chicanos that changed culture forever.”

Those who don’t know his directing work likely know Oriol’s most famous photograph: a close-up of a woman’s hands making the now iconic “LA” symbol with her fingers. Before establishing himself as a professional photographer, “My only job was Cypress Hill,” Oriol says. “So when they’d say, ‘Let’s take a break,’ I didn’t have a job no more. At that point I decided to dive headfirst into photography and video directing.”

Wrote The Times’ Daniel Hernandez in an April 2020 feature, “By bridging the gap between cultural gatekeepers and the urban landscape, Oriol and Mister Cartoon brought the roughest realms of L.A. street art and Chicano culture into the boardroom — and into your living room.”

In its own inimitable way, Cypress Hill has done the same with cannabis culture.

“We used to smoke every night,” says DJ Muggs (born Lawrence Muggerud), the group’s stoic co-founder, main producer and philosophical center. “We’d meet up after work on Cypress [Avenue] and smoke. One day we said, ‘Let’s just go inside and make music and smoke instead of standing outside all night.’ After what Muggs, 54, calls “a few years of demos,” they hooked up with Ruffhouse Records, eventual home of artists including Kriss Kross, the Fugees, Lauryn Hill and DMX.

As they established themselves, Cypress Hill had a conversation with a member of Public Enemy’s entourage that stuck with them, says B-Real: “ ‘You got to be about something. What are you about?’ Muggs saw the future right there.” A few years later they were getting banned from “Saturday Night Live” for defiantly smoking a joint during their set.

“You’d hear bands make little references in hip-hop before us,” said B-Real, “and reggae and the early forms of jazz music were referencing cannabis. But we were able to have an impact in the mainstream.”

As outlined in Oriol’s documentary, the Cypress Hill story has been marked with the occasional pothole. By the late 1990s, Sen Dog could be a spectral presence during tours, disappearing just before flight takeoffs or from hotel rooms after changing his mind about performing. Members of Cypress Hill don’t hide their frustration in the film. “I remember one time we were all at the airport and [Sen] said, ‘I’ll be right back,’ and this fool had called up somebody to pick him up,” Bobo, 53, recalls in the film. “We’re waiting for him to come back from the bathroom and he leaves and goes back home.”

Asked about those sequences, Sen Dog says that when Oriol told him he wanted to address the issues in the film, “I didn’t want to fake the funk or anything. He wanted to bring it to light [and] I’m like, ‘OK, cool. It’s about that time.’ ” Sen Dog describes the rough patch as the result of “anxiety and depression issues.”

That period prompted members to shift focus from the touring life and toward individual projects, endeavors that have likely prolonged the group’s life and continue to this day. Muggs, who famously produced House of Pain’s smash hit “Jump Around,” was recently given the keys to cosmic jazz artist Sun Ra’s archives for a forthcoming project involving Ra’s work. And although he didn’t produce any tracks on “Back in Black,” the beat maker was responsible for all the production on “Elephants on Acid,” Cypress Hill’s 2018 album, and will control the boards in the future, says B-Real, “for whatever our next Cypress Hill album produced by Muggs would be.”

Ever the hustler, B-Real will be celebrating 4/20 at his new Dr. Greenthumb dispensary near LAX, introducing a line of branded cannabis flower and plotting a multistate retail expansion. Sen Dog’s metal project, Powerflo, features former members of Biohazard and Fear Factory. Percussionist Bobo helps promote the legacy of his late father: In 2016, he facilitated the release of “Willie Bobo: Dig My Feeling,” a collection of previously unreleased recordings from the mid-1970s. And though Bobo’s presence on Cypress Hill tracks can be tough to spot, he remains central to Cypress Hill’s live experience.

On May 14, the group will participate in a live Verzuz battle against Queens hip-hop group Onyx, part of a boxing card at the Kia Forum. They’ll follow that with a string of dates opening for metal band Slipknot.

Touring, notes B-Real, has always been the lifeblood of Cypress Hill. “We built our reputation for live shows and we’ve kept ourselves busy enough to stay sharp. The mentality was always go do shows and win people over.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.