In the ’60s, the Beach Boys were gods. By the ’70s, ‘has-beens.’ But it’s not that simple

- Share via

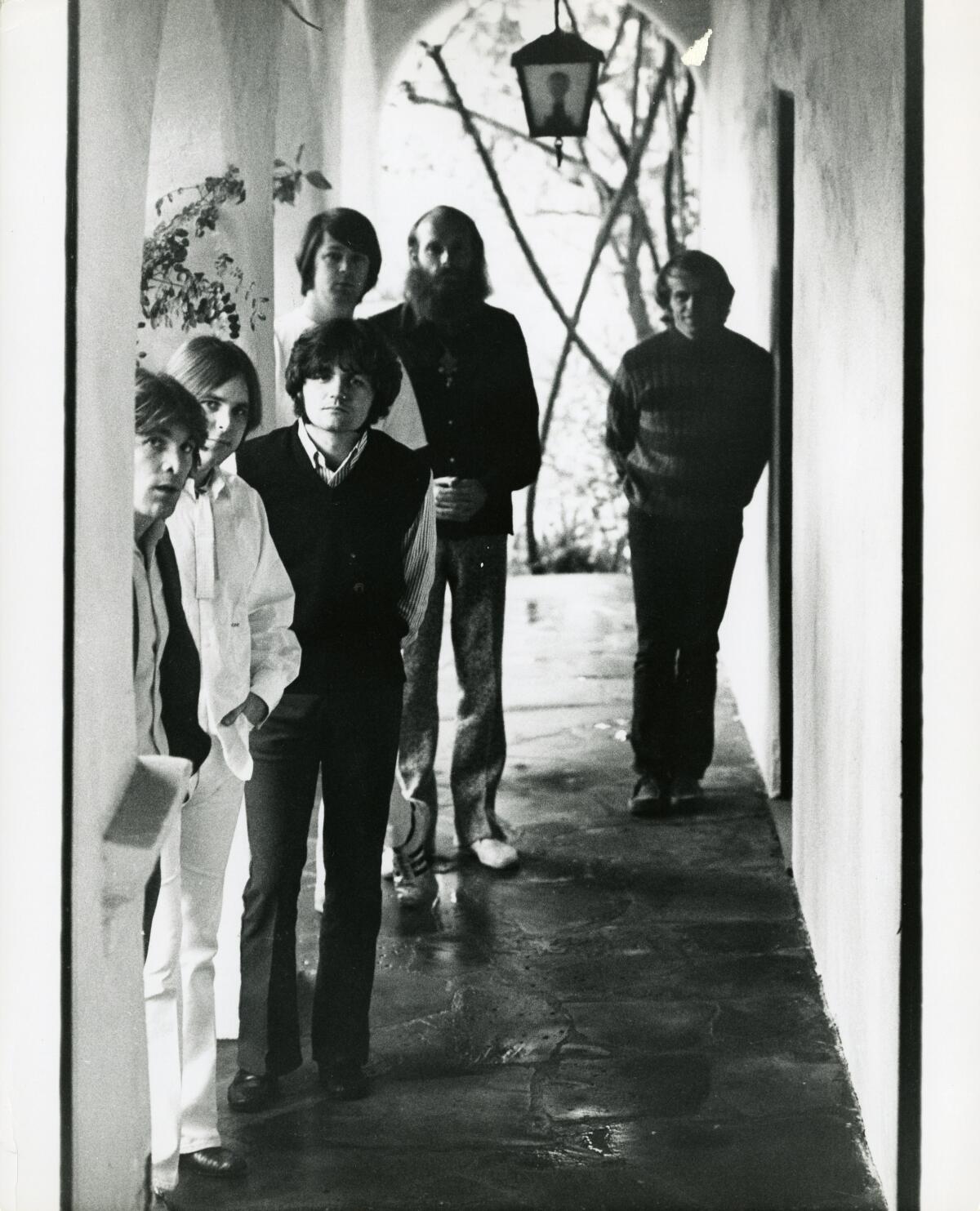

By 1970, the Beach Boys — one of the defining acts of 1960s pop, and arguably the closest thing America ever produced to a rival of the Beatles — were running low on good vibrations.

Work on “Smile,” the California band’s much-labored-over follow-up to 1966’s epochal “Pet Sounds,” had flamed out spectacularly, bringing unwanted attention to Brian Wilson’s mental health struggles. The albums they did complete, including 1968’s “Friends,” bombed among listeners tuned into Jimi Hendrix and the Rolling Stones. An ill-advised association with Charles Manson, who’d befriended Brian’s brother Dennis before 1969’s Tate-LaBianca murders, didn’t help, nor did the group’s lawsuit against its label, Capitol Records, which hardly seemed interested in reupping with the band in the first place.

Says Van Dyke Parks, the composer and veteran pop eccentric who’d helped Wilson shepherd “Smile” to nowhere: “These guys couldn’t get laid in a women’s penitentiary with a fistful of pardons.”

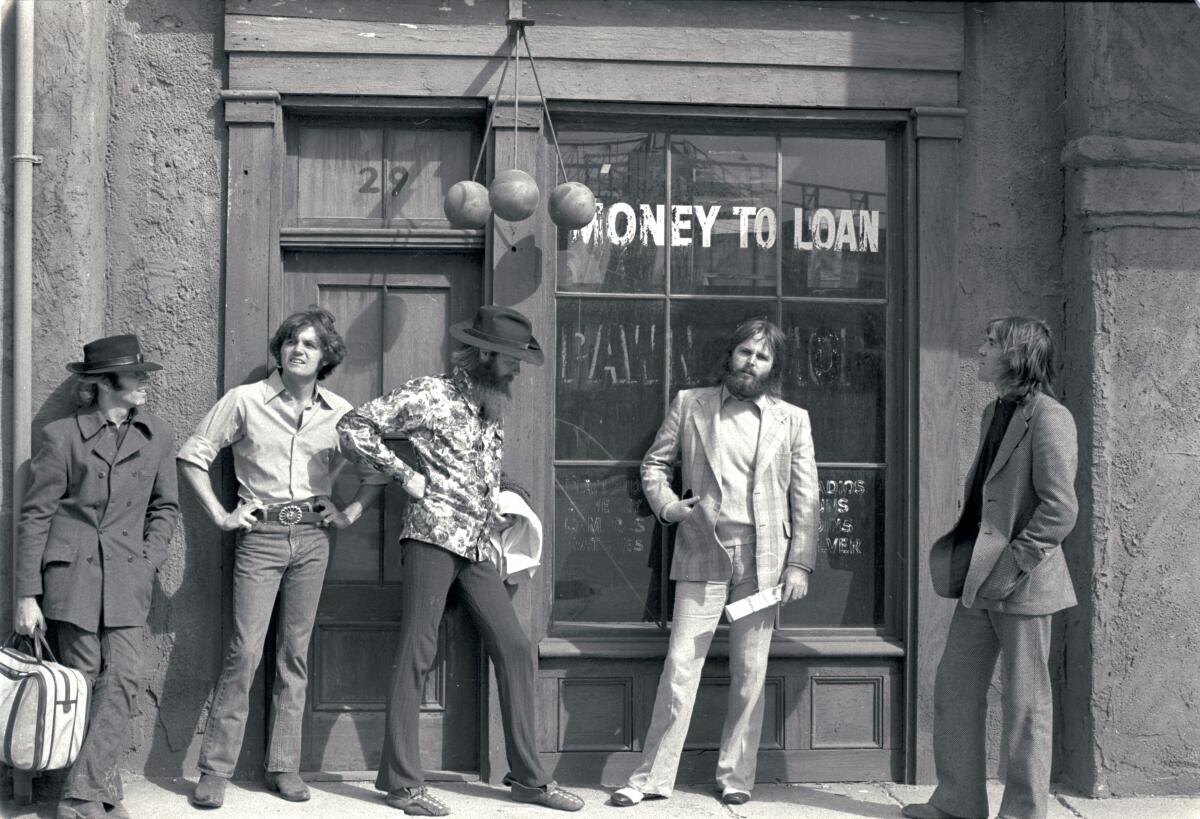

Expectations were low, then, as the Beach Boys entered a new decade with a new record deal. Yet the two LPs they made for Reprise in 1970 and ’71 — “Sunflower” and “Surf’s Up,” respectively — earned admiring reviews and went on to become cult classics beloved by serious fans and by other musicians. Now, half a century later, a just-released box set argues that these warm and winsome albums are worthy of canonization: With 135 tracks, including dozens of previously unissued demos and outtakes, “Feel Flows: The Sunflower & Surf’s Up Sessions” frames the band’s early-’70s period as a high point of homespun pop sophistication.

“We were just doing our own thing — expressing ourselves personally,” says Al Jardine, 78, who founded the Beach Boys with the three Wilson brothers (Carl, who died of lung cancer in 1998, was the third) and their cousin Mike Love. “As Brian began to withdraw a little bit, that encouraged the rest of us to really pour it on. It was a very creative time for us.”

Bruce Johnston, 79, who joined the group in 1965 initially to fill in for Brian on the road, calls “Sunflower” and “Surf’s Up” — both cut in a studio set up in the living room of Brian’s house on Bel-Air’s Bellagio Road — “the most fun I ever had recording,” in large part because he and the rest of the band felt so little pressure to make hits.

Delta variant be damned, many of our favorite artists are either performing at star-studded festivals, headlining concerts or releasing new albums this fall.

Which indeed they didn’t make: None of the albums’ singles — tunes like the yearning “Add Some Music to Your Day” and the soulful “Long Promised Road” — cracked the Top 40, while “Surf’s Up” went no higher than No. 29 on the album chart. (“Sunflower” stalled out at a once-unthinkable No. 151.)

“I can’t say the albums achieved the success we would’ve liked,” says Love, 80, who figures the Beach Boys were caught at the time between two radio formats: too hard for the AM pop in which they came up, too soft for the FM rock then taking over.

Producer Mark Linett, a longtime Beach Boys associate who assembled “Feel Flows” with Alan Boyd, says the band “was saddled with the baggage of their old image” — the smiles, the surfboards, the matching suits.

“Radio program directors were like, ‘I don’t care how good the music is, I’m not playing these has-beens any more than I’m gonna be playing Jan & Dean,’” Linett says.

Those who did listen, though — whether in 1970 or afterward — were charmed by the stirring melodies and adventurous arrangements the group devised in a newly collaborative mode, with each member writing and singing lead.

Dean Wareham, of the acclaimed indie-rock bands Luna and Galaxie 500, says he couldn’t have cared less about the Beach Boys when he was a teenager in the mid-’70s. “As the culture started changing, they just seemed so out of step,” he says. Years later, a fellow musician, Pete Kember (a.k.a Sonic Boom) of Spacemen 3, turned him on to what he’d missed, including “Forever,” an achingly pretty Dennis Wilson ballad from “Sunflower” that Wareham eventually covered.

“It’s such a beautiful song,” he says of “Forever,” which Brian Wilson once described as “a rock ’n’ roll prayer.” (The new reissue features a stunning a cappella mix of the tune that showcases the group’s heavenly vocal harmonies.) Looking back, Wareham compares the Beach Boys in the early ’70s to Roy Orbison and the Everly Brothers in the late ’60s — titans of rock’s first generation who “were still making these great records that no one paid any attention to.”

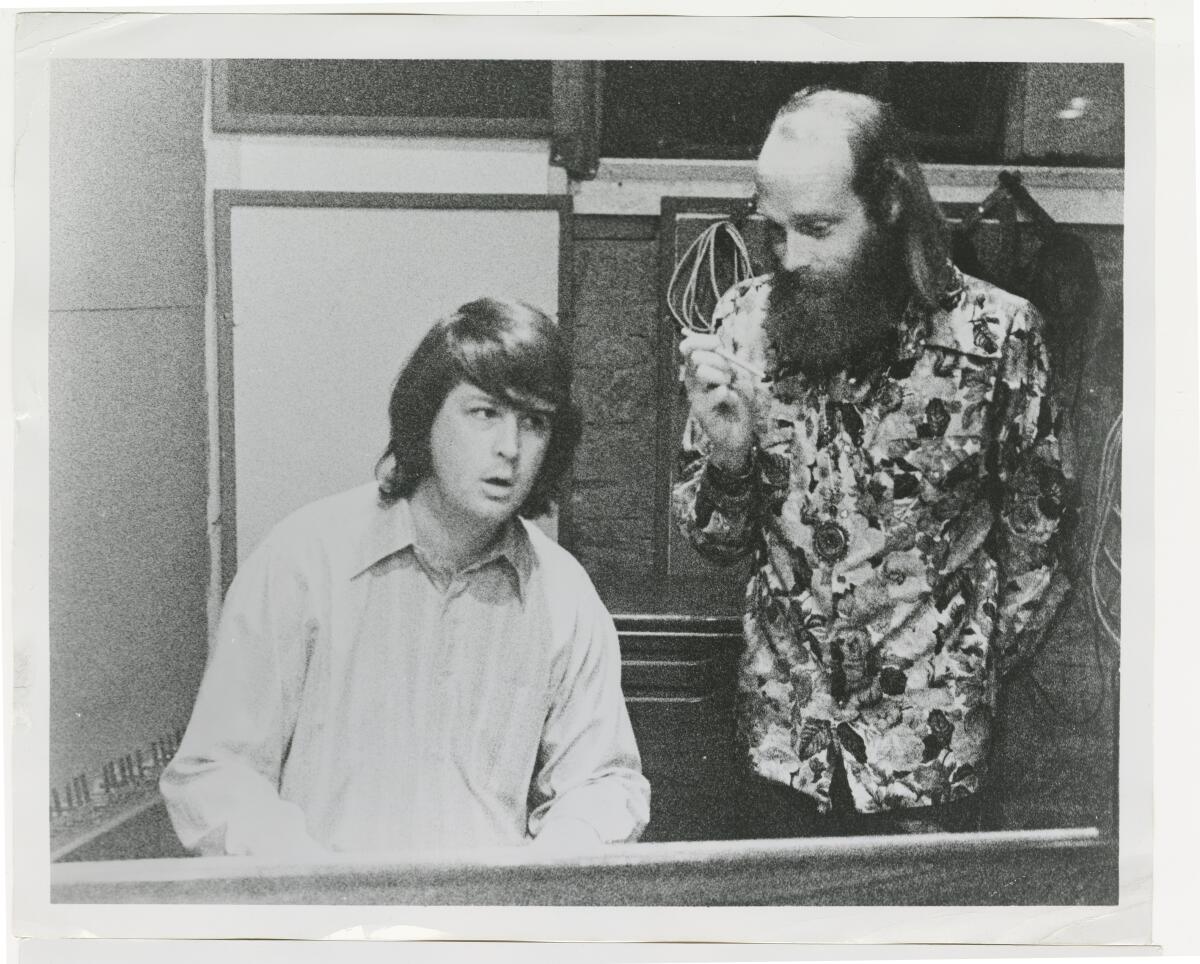

In a way, the Beach Boys’ under-the-radar positioning was a creative boon as they recorded “Sunflower,” which the Village Voice’s Robert Christgau later described as “far more satisfying, I suspect, than ‘Smile’ ever would have been.” Working with their trusted engineer Stephen Desper, they’d built the studio at Brian’s mansion to make it easier for the band’s fragile mastermind to participate. (Wilson, 79, was not available for an interview but wrote in his 2016 memoir that, along with drug troubles, he’d lost the “control and confidence” that powered his world-changing work in the ’60s.)

“The studio was right below Brian’s bedroom, so it was very convenient for him to come down when the thought moved him, rather than having to go down to Western,” Love recalls, referring to the complex on Sunset Boulevard where the Beach Boys made “Pet Sounds” and “Good Vibrations.”

)

Yet they ended up with a protective environment in which they all felt free to experiment. “You’ve heard of a man cave — we had a band cave,” Johnston says with a laugh. According to Jardine, “We’d show up every day at pretty much the same time. Brian had a fantastic … larder, is that the right word? Big walk-in with refrigerators and freezers. We’d just make ourselves at home and get the project going,” a laid-back vibe that comes through in songs like “Deirdre” and “Our Sweet Love.”

“I don’t know why Marilyn put up with us,” Jardine adds of Brian’s wife at the time.

The band felt a similar warmth about its new label home. Parks, then working for Reprise’s parent company, Warner Bros., had “campaigned vigorously” to get the band signed, he said, because he “felt a sense of debt to Brian” after “Smile’s” failure tarnished Wilson’s reputation.

“He was persona non grata, and that made me angry because he was a guy who built an industry,” Parks says. “He created sales figures that are incomparable to anybody else; he created jobs in the American workforce. I thought the record business owed that man a living.”

Johnston called Reprise, known at the time for acts such as Joni Mitchell and Randy Newman, “an insanely cool fan club with a checkbook. They were in love with their artists.”

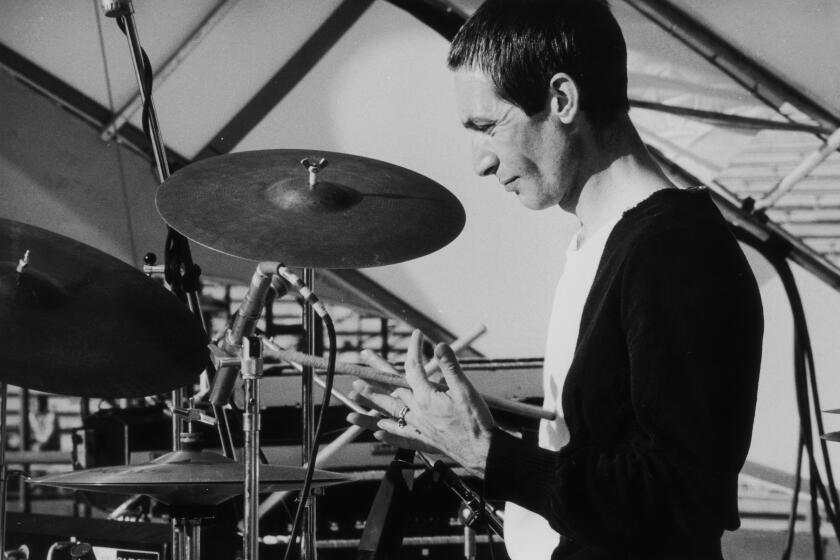

The Rolling Stones drummer, who joined the group in 1963 and never missed a gig, died Tuesday at age 80.

Not that the label didn’t meddle. Lenny Waronker, the label’s head of A&R, remembers driving up to Brian’s house after hearing a rough version of “Sunflower” to “tell them we were concerned that there wasn’t a single or something — one of those meetings you hate to do.” What he coaxed out of them, though, was perhaps the weirdest track on the album: “Cool, Cool Water,” a trippy number (complete with Moog keyboard breakdown) that evolved out of a fragment from “Smile.”

“As great as it was, the record probably needed some kind of structure to it,” Waronker says. “I didn’t think it was a hit, but I didn’t care. It was a bold move.”

Others in the Beach Boys’ world were more motivated to sell records. After “Sunflower” landed with a thud, Jack Rieley took over from Nick Grillo as the band’s manager; Johnston says Rieley, who died in 2015, proposed issuing “Surf’s Up” without individual songwriting credits “to blow a little smoke and make everyone think Brian was back.”

Johnston balked, not least because he wanted fans to know he’d written “Disney Girls (1957),” a wonderfully syrupy ballad with memories of “Patti Page and summer days on old Cape Cod.” Says Johnston proudly: “I’m the saccharine shlockmeister of the Beach Boys.”

“Surf’s Up” also contains a number of songs about the environment — among them “Don’t Go Near the Water,” about pollution of the ocean, and “A Day in the Life of a Tree,” which the popular indie-rock band Yo La Tengo has covered — as well as “Student Demonstration Time,” Love’s post-Kent State rewrite of the old Leiber/Stoller classic “Riot in Cell Block No. 9.”

Jardine admits the topical stuff was a bit of a stretch, especially for him. “If the Beach Boys were out of the flow, I was like twice out of the flow,” he says. At the time he lived with his family in a “beautiful home” in Mandeville Canyon and never ventured east of Brian’s place. “All the stories about Laurel Canyon — I didn’t hang with those folks,” he adds with a laugh.

Yet “Surf’s Up” endures thanks to gorgeous mini-symphonies like “’Til I Die” and the majestic title track, both Brian star turns, and quirky rockers like “Take a Load Off Your Feet.” Among the live cuts included on “Feel Flows” are a handful from this era that suggest the Beach Boys — whose “concert fees had gone down the tubes because people didn’t take us seriously,” according to Johnston — were more muscular onstage than is widely remembered.

“Those shows were so cool,” Johnston says. “I wore combat boots and blue jeans. Fantastic time. You should’ve been at the one we did at the Fillmore East” — a legendary 1971 gig where the Beach Boys jammed with the Grateful Dead before an audience that reportedly included an enthusiastic Bob Dylan.

With various shifts in membership, the Beach Boys continued to make records throughout the ‘70s, though the huge success of 1974’s “Endless Summer” compilation made the lure of the nostalgia circuit hard to resist. Dennis drowned in Marina del Rey in 1983; “Kokomo” topped the Hot 100 in 1988. Today there are essentially two Beach Boys: a touring oldies act with Love and Johnston and the outfit Wilson uses (which includes Jardine) to perform his music.

Last year the group’s internal tensions spilled into view when Love and Johnston played a fundraiser for then-President Trump in Newport Beach, which led Wilson and Jardine to issue a statement saying they had nothing to do with the booking. But there’s talk of a 60th-anniversary reunion, and the surviving members recently announced that they’re working with Irving Azoff, the veteran music-biz power player, to “monetize the Beach Boys’ legacy,” as Rolling Stone put it.

Given how much Beach Boys content is already out there, could there be much left to exploit? Boyd and Linett say yes; they’ve already started gathering material for a box set devoted to the band’s next pair of mid-period albums, 1972’s “Carl and the Passions — ’So Tough’” and 1973’s “Holland.” Jardine, for one, is eager to hear what they find.

As he went through the outtakes they’d sent him to authorize for “Feel Flows,” Jardine’s mind was blown when he came across a verse from Brian that he’d never heard in “Don’t Go Near the Water” — a few lines that capture the strange blend of beauty and melancholy that has always defined the Beach Boys.

“I was like, ‘Where in the hell did this come from?’” he says. “I guess Brian came down and recorded it one night.

“Would you like to hear what he sang?” Jardine asks.

“‘Don’t go near the water / Don’t you think it’s sad? / Don’t go near the water / I think it killed my dad.’

“Pretty deep, huh?”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.