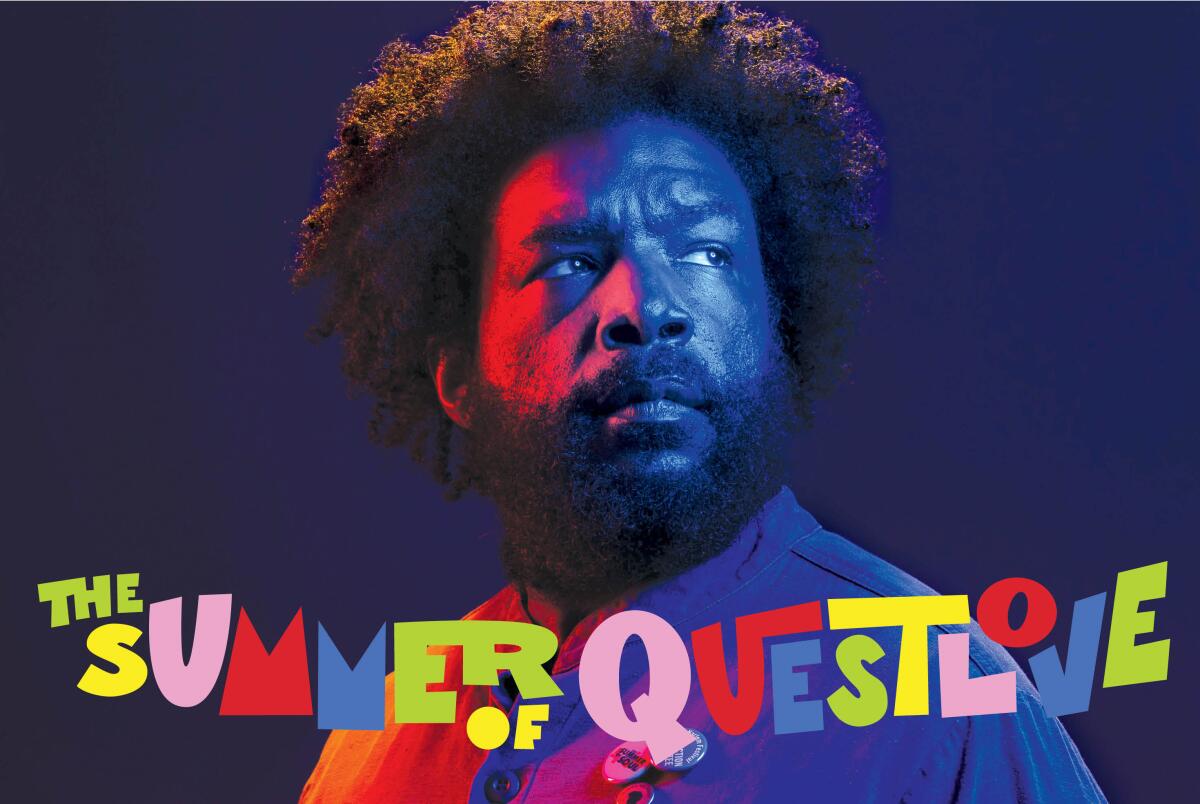

An answer to ‘pain porn’: Questlove on celebrating Black joy with ‘Summer of Soul’

- Share via

The last thing Questlove needed was another job.

Plenty of musicians and actors have branched out into other mediums, but no one has done it more broadly or sagely than Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson. He’s the drummer in the Roots, an enduring rap group; music producer; Broadway producer; podcast host; author; DJ; adjunct professor; and backbone of “The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon” band. He’s a rare behind-the-scenes talent who’s known to the public.

What unites all of his jobs is music expertise, especially in the category of Black music. Questlove is a human Wikipedia, a 6-foot-2 World Book, a one-man Library of Congress. He doesn’t search Google, Google searches him. If you want to know who played drums on a 1973 Jackson 5 B-side, or who made the suit Otis Redding wore at the Monterey Pop Festival, you call Questlove.

Joni Mitchell’s peers, progeny, admirers and Mitchell herself reflect upon on her classic 1971 album ‘Blue,’ released 50 years ago today.

“Music history is kind of in my DNA,” he said one recent morning, during an 80-minute conversation over peppermint tea in the lobby restaurant of a Midtown Manhattan hotel. His parents were professional musicians, as was a grandparent, but his knowledge is as much from thoughtfulness as from DNA. Questlove, 50, habitually finds connections between disparate events, and conversation topics range from his appearance on the PBS series “Finding Your Roots” to Prince’s autobiography, as he recounts the unlikely path that led to his debut as a film director on “Summer of Soul ( … Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised),” which won the Grand Jury Prize and the Audience Award at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year and opens nationwide in theaters on July 2.

When two film producers contacted him in 2018 and claimed to have footage of a 1969 Harlem music festival that starred Gladys Knight, Sly and the Family Stone, B.B. King, Nina Simone, the 5th Dimension and a 19-year-old Stevie Wonder, Questlove was skeptical. “The arrogant music snob in me was like, ‘That never happened. If it had happened, I’d know about it.’” The producers told him director Hal Tulchin had filmed the festival, and the film sat in his basement for 50 years.

He asked old-school New Yorkers like director Spike Lee, producer Nile Rodgers and author Nelson George if they’d heard of the event, and they shrugged. But the producers — Robert Fyvolent, an entertainment attorney and former studio executive at Disney, Sony and Newmarket; and former Miramax and Fox Searchlight executive David Dinerstein — persisted. Questlove was sure the footage had some kind of fatal flaw. “I was wondering, what’s the catch? Like, OK, the film quality looks more like a soap opera than a movie, or it’s all Beatles covers,” he says with a laugh.

The producers met with Questlove at the “Tonight Show,” then played their ace. “When they showed me the footage, 100%, my jaw dropped. Like, ‘You’re telling me there’s more than 40 hours of this footage and no one’s ever seen this s—?’ I couldn’t figure out why this sat in someone’s basement for 50 years.”

Ahmir ‘Questlove’ Thompson’s new documentary ‘Summer of Soul’ unearths the thrilling history of a 1969 music festival in Harlem.

When Fyvolent and Dinerstein asked Questlove to direct a feature film using the footage, he demurred; one music video was the extent of his directing experience. “For four months, I tried to duck and dodge this thing,” he says. “I said, ‘Ava DuVernay, that’s who you really want.’” (“I feel like that might’ve been an internal conversation he had,” Fyvolent said in a phone interview. “I don’t remember him trying to talk me out of it very hard.”)

Eventually, Questlove realized he didn’t want anyone else to tell this story because no one else could do it as well as he could. His experience and his standing as a music scholar were advantages when it came time to interview musicians who’d performed at the festival and people who’d attended it. “No one else would think to ask Marilyn McCoo [of the 5th Dimension] how exhausting it is to code switch for two different [white and Black] audiences,” he says.

“Summer of Soul” is a majestic, spirited, thought-provoking movie, and in the course of our interview, it became clear that the person it provoked most was Questlove. By the end, he understood why this historical footage had been neglected for so long, and he didn’t like the answer.

In the summer of 1969, Hal Tulchin was a hardened 42-year-old director of commercials, game shows and Vegas-type entertainment specials. Nothing in his resume reflected an interest in Black music, but when he heard about the Harlem Cultural Festival, a series of free, open-air concerts at Mount Morris Park in Harlem during the summer of 1969, he decided to shoot it on spec and then try to sell the footage. The equipment he used, five portable videotape cameras, was a far cry from what he’d used with Wayne Newton. “It was a peanuts operation, because nobody really cared about Black shows,” Tulchin said, with understandable bitterness, in a 2007 interview with Smithsonian magazine.

The dazzling six-week event also included jazz musicians Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln and Hugh Masekela, the Chambers Brothers, salsa great Ray Barretto, the Rev. Jesse Jackson (who spoke movingly of his final moments with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. after he was shot) and a flurry of gospel stars: the Staples Singers, the Edwin Hawkins Singers, Clara Walker and the Gospel Redeemers, and Mahalia Jackson, who summoned Mavis Staples for an impromptu duet on one of King’s favorite songs, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” one of the film’s many highlights. Great as that talent list is, TV executives thought it would make for a niche show that wouldn’t attract white viewers.

“Hal was a little naïve, thinking that because he’d sold other TV specials,” he’d be able to sell this one, Fyvolent says. “The pipeline was very narrow in those days; three networks. He didn’t get the response he hoped.”

Latino artists are a rarity in country music, while white artists wink at the culture with songs about señoritas or tequila shots in Juarez.

After Fyvolent learned about the festival and the footage from a college friend, he went sleuthing and in 2007 found Tulchin in Bronxville, N.Y. “My father was really frustrated,” says Sasha Tulchin, Hal’s daughter. “He gave up for a long time, because nobody cared. But he was deeply passionate about things, and he said, ‘This will happen at some point.’”

Fyvolent got a better response than Tulchin did, but discussions on financing and distribution deals dragged on. The budget was considered high for a music documentary, and some executives were scared off by the task of securing licenses from the artists involved. There was also the challenge of converting the footage Tulchin shot in the budget-conscious DVCAM format, which only a few production houses are now able to transfer. In September 2017, Hal Tulchin died at the age of 90.

After he signed on in 2018, Questlove had to decide what kind of movie he wanted to make. He imagined a story in the style of “Amazing Grace,” director Sydney Pollack’s film about a 1972 Aretha Franklin performance. Pollack’s entire film takes place inside the New Bethel Baptist Church in Watts. “It was a bold choice, not to have any context of what was happening that day,” Questlove says. He decided on a similar approach — just performance, no talking heads or archival footage.

One day, out of curiosity, he tweeted a question: Had any of his 3 million followers attended the Harlem Cultural Festival in 1969? He was inundated with DMs. One of the first people to respond was Musa Jackson, an event producer who was 5 years old at the time. Questlove was skeptical that his memories would be worthwhile, but he screened some of the footage for Jackson, whose response changed the direction of the film. “Musa said, ‘Look, this is my first memory in life.’ I realized this isn’t just a movie. I literally watched a person get his life back.” Jackson became both an emotional and comedic anchor in the film; at one point, he says the festival “smelled like Afro Sheen and chicken.”

Questlove dropped the Sydney Pollack approach and added more interviews. In one poignant scene, McCoo becomes teary when she watches the footage of herself.

“It was special, because we were getting a chance to perform for a vast audience in Harlem, who didn’t necessarily know our music,” McCoo says during a phone interview that includes her singing partner and husband of more than 50 years, Billy Davis Jr. “It was wonderful to see Sly and B.B. King.”

“B.B. King when he was thin,” Davis interjects.

The 5th Dimension’s soft-pop hits were at odds with the times, almost a Black Yacht Rock, and some people of color dismissed the group as “too white.” “They thought a Black group had to sound like Motown,” Davis says. “Protest songs was going on, ‘Something’s happening here,’ and all that. And here we come with ‘Up, Up and Away,’ this sweet little song. Come to find out, that was just what the nation needed.”

The group’s crossover appeal didn’t insulate them from bad experiences on the road. “Jim Crow was alive and well,” Davis recalls. One of Questlove’s revelations was how difficult touring was in the ’60s. “Mavis Staples and Gladys Knight told me almost identical stories: They’d make sandwiches the night before if they were driving in a sundown town.”

Questlove realized he couldn’t depict the music series as an apolitical event, because it wasn’t apolitical. “This festival was thrown to keep Black people occupied from rioting, as they did a year before when Martin Luther King died,” he says.

In the footage of Stevie Wonder’s festival appearance, Wonder mentions the moon landing and the crowd boos. Questlove was curious about the response, and found “how much disdain Black people had for the moon landing. I didn’t know.” He added several scenes that address that disdain.

Along the way, he realized the answer to his own question about why Tulchin’s footage sat unused for decades: Black erasure, a broad term that encompasses the idea that American history is written through the white gaze, and Black voices are ignored, forgotten or worse.

With “Summer of Soul,” Questlove was trying to correct one example of Black erasure. The story of people of color in the late ’60s is largely focused on protests, beatings, marches and the murders of King and Malcolm X.

“I call it pain porn,” Questlove says. Seeing so many Black stories about slavery and suffering, he says, “is exhausting. We have other stories and other experiences too. One element [that’s missing] is Black joy. At what times were we shown in a non-minstrel light, where it’s actual joy?”

The 1970s TV show “Soul Train,” he continues, “was the first time you got to see the Black teenager celebrate their lives. Their fashion, their beauty, their sexuality, their talent. It’s not mired in civil unrest or riots. ‘Soul Train’ is my north star. In my house, it plays on a continual, 24-hour loop, because that’s my happy place in life.”

Questlove points out that David Ruffin of the Temptations appeared at the festival in full showbiz gear (“Dude, he’s in a wool tuxedo in the middle of August”) whereas Sly and the Family Stone, an interracial band, dressed in everyday threads. The contrast depicts a time when Black music was changing generations and styles. “When Sly comes on stage, you see older people looking like, ‘What’s this?,’ and younger people losing their minds. It’s an absolute lesson in how transformative they were.”

He points to an adjacent change that’s evident in the many giant Afros in the crowd. “1969 is also the paradigm shift for us embracing the idea of Black is beautiful. Before that, we were damn near taught to hate ourselves. I remember fights in eighth grade where, if a kid really wanted to insult me, he’d call me African. It was an insult.”

Britney Spears has been a media and pop culture object of derision, pity and indifference to her humanity. On Wednesday, she stood up for herself.

When the pandemic struck, Questlove bought a farm outside New York to escape the city. “I’m a farm-purchasing, Croc-wearing, 6 a.m.-meditating cliché,” he laughs. “I’ve morphed into the person I used to laugh at.” But the COVID delay gave him time to reflect on the relevance of the film to the era of Black Lives Matter. “When there was civil unrest and protest in the streets last year, it wasn’t lost on us: it’s an exact mirror of 50 years ago. It’s still happening.” He added modern footage of protests, which he says completed “the story that we want to tell.”

“This film would have brought my dad to tears,” says Sasha Tulchin, who saw it at Sundance. “He would’ve been so proud.”

“What I hope creators take away from this,” Questlove says, “is that you’re able to make a living and still make a difference. I know that sounds like the ‘ABC Afterschool Special.’ But I’m dead serious. We live in a time in which cultural figures are big businesses, and there’s something to lose. They’re getting more and more afraid to speak out. But there’s people that use their voice for activism and I just want to steer creators in that direction, like a sheep dog.”

It’s clear that Questlove wishes this film had come out in the 1970s because he would’ve seen it as a kid and had other images of Black joy in his head. That film didn’t exist, so he made it.

Questlove has many other careers to return to, but he may have caught the directing bug. He’s working on a Sly Stone documentary, and says he’s recorded six hours of interviews with the erratic genius. “Believe it or not, Sly is the easy part,” he chuckles. “Larry Graham, I got to work some more.”

And even though “Summer of Soul” runs almost two hours, it’s only a fraction of what Hal Tulchin shot. “I swear,” Questlove exults, “we still have 40 hours of footage left.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.