Listening to Phil Spector: A three-minute thrill ride, then a reckoning with evil

- Share via

Pick a classic Phil Spector production. It actually doesn’t matter which. The opening eight bars of the Ronettes’ 1963 smash “Be My Baby” are among the catchiest in American song, a thump, thump-thump, splash rhythm that rockets into outer space with sizzling shakers and snares that boom like shotguns. When Ronnie Spector’s soaring voice swoops in to steal the thunder, the combined eruption is undeniably thrilling.

Or take “Strange Love,” the Darlene Love-propelled gem that opens with a frolicking schoolyard melody before turning into a galloping riot of string- and percussion-driven weirdness as Love sings of a creeper whose brand of affection is so concerning that she “can’t take it, can’t take it no more.” The entirety of “A Christmas Gift to You,” Spector’s canonic holiday album, is a rush of joyous girl-group energy. “River Deep, Mountain High” — my, oh my.

Phil Spector was hospitalized after he became ill with COVID-19, said a source familiar with his medical condition.

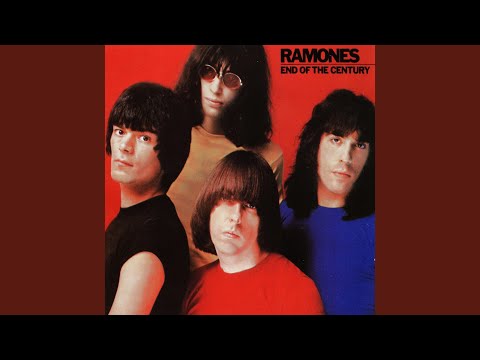

Record producer, songwriter and studio auteur, Spector — who died Saturday at age 81 in a Northern California hospital of complications from COVID-19 — was one of the most influential musical creators of the 20th century. It’s right there in the grooves, every clack of clave, doo-wop wail, stealthy saxophone run, chorale explosion, jangle of bells and rat-a-tat percussion breakdown. Among the first American hitmaker-producers of the record era to combine his sonic ideas and single-minded drive to become a chart-busting one-stop shop, Spector laid the foundation for auteur-producers such as Rick Rubin, Dr. Dre, Timbaland and Mike Will Made It.

Equal parts composer, maestro, producer, director and impresario, Spector helmed his sessions at Gold Star Studios in Hollywood with vocalists the Ronettes, Crystals, Gene Pitney, the Righteous Bros. and others on songs including “To Know Him Is to Love Him,” “He’s a Rebel,” “Unchained Melody, “Walking in the Rain” and “And Then He Kissed Me” as if each record were preordained.

The result was a string of breathtakingly deep hits that helped guide the trajectory of the 1960s and beyond. Although his reign on the charts only lasted half a decade, echoes of Spector’s famed “wall of sound” production technique can be heard in the work of Bruce Springsteen, the Beach Boys, Katy Perry, Beck and Best Coast.

And, and, and: Spector was a murderer. A pistol-wielding kidnapper and career violent abuser who was convicted of the 2003 killing of Lana Clarkson.

These truths exist side by side, which is why I hesitantly raised my hand to write about Spector’s work as a producer and the power he unleashed on the world from a storefront recording studio on Santa Monica Boulevard in Hollywood. To write about his creations is not to eclipse his killing of Clarkson, the details of which are easily accessible. Terrible people have made great art, a notion that writer Fran Lebowitz discusses in her new Netflix series, “Pretend It’s a City.” Asked whether there were any writers she won’t read, Lebowitz replied by citing novelist Henry Roth, who she explained “was discovered to have had sex with his sister. And it was horrible, but no, it wouldn’t keep me from reading him.”

She added, “Of course, you can’t read someone in the same way.”

Be My Baby, as performed by the Ronettes.

Like most, I stopped being able to listen to Spector’s music the same way the moment he was arrested for Clarkson’s murder. But that doesn’t diminish the glory of the Crystals’ “Da Doo Ron Ron,” the Paris Sisters’ “I Love How You Love Me,” the Treasures’ “Hold Me Tight” or Spector’s harrowing production on the Righteous Brothers’ massive “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling.”

“Working with Phil Spector was working with the best,” Ronnie Spector, Spector’s ex-wife and most enduring collaborator, wrote in a statement after his death. “So much to love about those days. Falling in love was like a fairytale. The magical music we made was inspired by our love.” The namesake of the Ronettes tempered her statement by calling him “a brilliant producer, but a lousy husband.”

At peak success in the early 1960s, Spector described his three-minute pop gems as “little symphonies for the kids,” and the moment was right for them. A generation of teenagers was transforming boom-time America — and the Billboard charts — and the scrawny Spector manifested their desires. The best of his singles were so propellant that they upended pop music in the pre-Beatles 1960s by delivering action, swing and excitement to stagnant pop charts then weighted down by Pat Boone-style pablum.

Growing up just south of Melrose and Fairfax, the son of a single mom and a father who died by suicide when Spector was a boy, the prime orchestrator of teenage love and angst lived just a 10-minute cruise to downtown Hollywood, where dozens of recording studios and labels operated. He got his first professional music lessons around the corner from Wallich’s Music City at Sunset and Vine. Some days after school he would race home to turn on the radio and practice guitar along with KGFJ disc jockey Hunter Hancock.

A shy kid, he landed his 1958 debut single, “To Know Him Is to Love Him” by the Teddy Bears, at No. 1 when he was 18 and just out of Fairfax High School.

River Deep, Mountain High by Ike & Tina Turner

As he matured, Spector’s aural signature — huge, echoed percussion, prominent string arrangements and charismatic, pitch-perfect Black belters — became immediately identifiable. Some of the earliest singles by the Beatles and Rolling Stones reek of Spector’s influence and his production style remains an archetype. It didn’t always overwhelm; Pitney’s “Every Little Breath I Take” and the Righteous Brothers’ “Unchained Melody” were more contained but still bursting at the seams. He knew talent when he heard it: Session players on Spector’s classic hits included Sonny Bono, Leon Russell, Glen Campbell, bassist Carol Kaye and drummer Earl Palmer.

As the puppet master, Spector was a hands-on operator. A millionaire by the time he hit 23, he booked studio time, conferred with writers and directed studio engineers. He accomplished a lot in pre-production, spending entire days, for example, getting the percussion properly amplified in one of the studio’s four echo chambers, working with pounders including Bono and Palmer on woodblocks, castanets, bells, tom-toms, timpani and congas.

If you want to get technical, the so-called Wall of Sound was actually angled back, like a rising wave just before a surfer catches it. With dozens of musicians arranged by timbre and tone and surrounded by strategically placed microphones, Spector and engineer and unsung hero Larry Levine captured the sound of the room, the instrumental resonance and, somehow, the emotional heart of the record. An engineering classicist, Spector famously rejected the burgeoning hi-fidelity stereophonic advances in sound reproduction. His motto: “Back to mono.”

Before takes, Spector was known to roam the room coaching musicians as if he were Quentin Tarantino prepping actors before an action sequence. As the late producer and musician Jack Nitzsche recalled to writer Harvey Kubernik when directing guitarists, Spector “would whisper in their ears, ‘Dumb — don’t do anything. Just play eighth notes.’ It was hard for any of the guitarists to breathe or stretch out on the records.”

Critics bemoaned so much sound, which stretched the capacities of AM radio at the time and prompted some to complain of his productions’ expressionistic chaos. Spector acknowledged the so-called “muzziness,” but his ears registered it otherwise, saying that the onslaught “adds up to musical guts. There’s gotta be guts in music. Make it too sharp and you lose out. You can call it cloudy if you like, but I just call it the guts of the music.”

The Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson was mesmerized by Spector’s onslaught. In the years before Wilson produced “Pet Sounds” using Spector’s techniques, Wilson would drop by Gold Star to observe sessions. Wilson has said that the Crystals’ 1962 smash “He’s Sure the Boy I Love” “opened up a door of creativity for me like you wouldn’t believe. Some people say drugs can open that door. But Phil Spector opened it for me.” Wilson later added that Spector’s work led him “to design the experience to be a record rather than just a song.”

“He’s a Rebel,” written by Spector collaborator Pitney, tapped generational angst, hormonal hunger and a baritone-blaring brass run to advance a song about a Romeo-and-Juliet-style romance. “Da Doo Ron Ron” starts on a Monday when our heroine meets Bill, continues when he walks her home and ends later that night after a little da-doo-ron-ron. “You never close your eyes anymore when I kiss your lips, and there’s no tenderness like before in your fingertips” sings the Righteous Brothers’ Bill Medley to open “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling.” Measure by measure the tension builds as the singer lays out his heartbreaking evidence. When the chorus arrives, Spector scores it as if the world’s imploding.

“In those songs, the story line was as clear as clear could ever be,” recalled the late Leonard Cohen, upon whom Spector famously pulled a gun during one notorious session. “The images were very expressive — they spoke to us all. Spector’s real greatness is his ability to induce those incredible little moments of poignant longing in us.”

The bridge on “Then He Kissed Me” — the moment of lip-locking impact, which singer Dolores “LaLa” Brooks belts with exuberance — swirls with strings that somehow capture the hormone-in-a-bottle rush of falling in love. Spector’s production of the King-Goffin song “He Hit Me (It Felt Like a Kiss)” powers the upsetting song with a sorrowful menace.

For Spector, the hits didn’t keep coming. By the time the Beatles invited him to work on “Let It Be” with them, the producer hadn’t had a major hit in years, and was stinging from the failure of Ike and Tina Turner’s roaring take in “River Deep, Mountain High” to make a sales dent. The Beach Boys’ Bruce Johnston compared Spector in those periods to “a little boy who does something really cute and gets applauded for that, and so he starts figuring out how to get the applause back, but then it’s not quite as cute again. I think Phil started believing his own legend and press.”

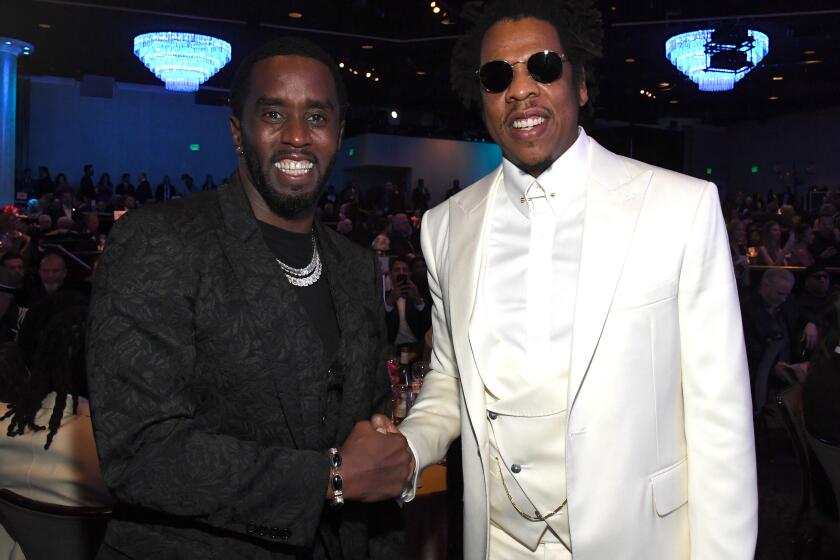

The Ramones hired him to produce their fourth album, “End of the Century.” It didn’t go well, according to Dee Dee Ramone.

“I like beauty to be instant. Not to be labored over, I don’t like music to be a hustle. I think we can just go into a studio and do it and not be frustrated. Phil seemed to be frustrated with us.” Ramone added that Spector “wasn’t the most friendly guy I’ve ever met. He tried to be friendly but then he had his guns on him and he wouldn’t let me out of his house for a couple of days.”

Spector’s arrogance hobbled many an artist, not least of which was his ex-wife Ronnie, who once told NME that he “was always telling me that I was nothing, that it was his production and his writing that made me and that, without him, I wouldn’t make it again.”

He also proved unwilling to change with the times. A rigid aesthete who demanded subservience in the studio, he bemoaned the rise of the Laurel Canyon folk scene, and steadfastly refused to let his Southern California upbringing seep into his sound. “They thought Gold Star was in New York,” Spector told Kubernik, adding that his techniques were “hardly typical California stuff. There are no four-part harmonies on my records. Maybe 32-part harmonies.”

He concluded his point with a dig at Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young: “Anybody laid-back in this room, get the f— out of here!”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.