The story behind the song behind one of the great music scenes in movie history

- Share via

A song needs to be exceptional if it’s going to occupy 10 minutes of a 69-minute movie.

Steve McQueen’s “Lovers Rock,” one film in the Oscar-nominated director’s five-part “Small Axe” anthology series for Amazon Studios, tracks the course of a “blues party” thrown by first- and second-generation West Indian immigrants in an apartment in London in 1980. Midway through the night, one of the DJs plays Janet Kay’s 1979 hit “Silly Games,” a sweetly yearning ballad that typifies the sentimental variant of reggae for which the movie is named.

What happens next constitutes one of the most patient and loving celebrations of music ever captured on film. The DJ stops the music so that the slow-dancing partygoers can sing the entire song a cappella, giving it the sacred quality of a hymn. It is a spontaneous ritual of connection and endurance in a hostile world.

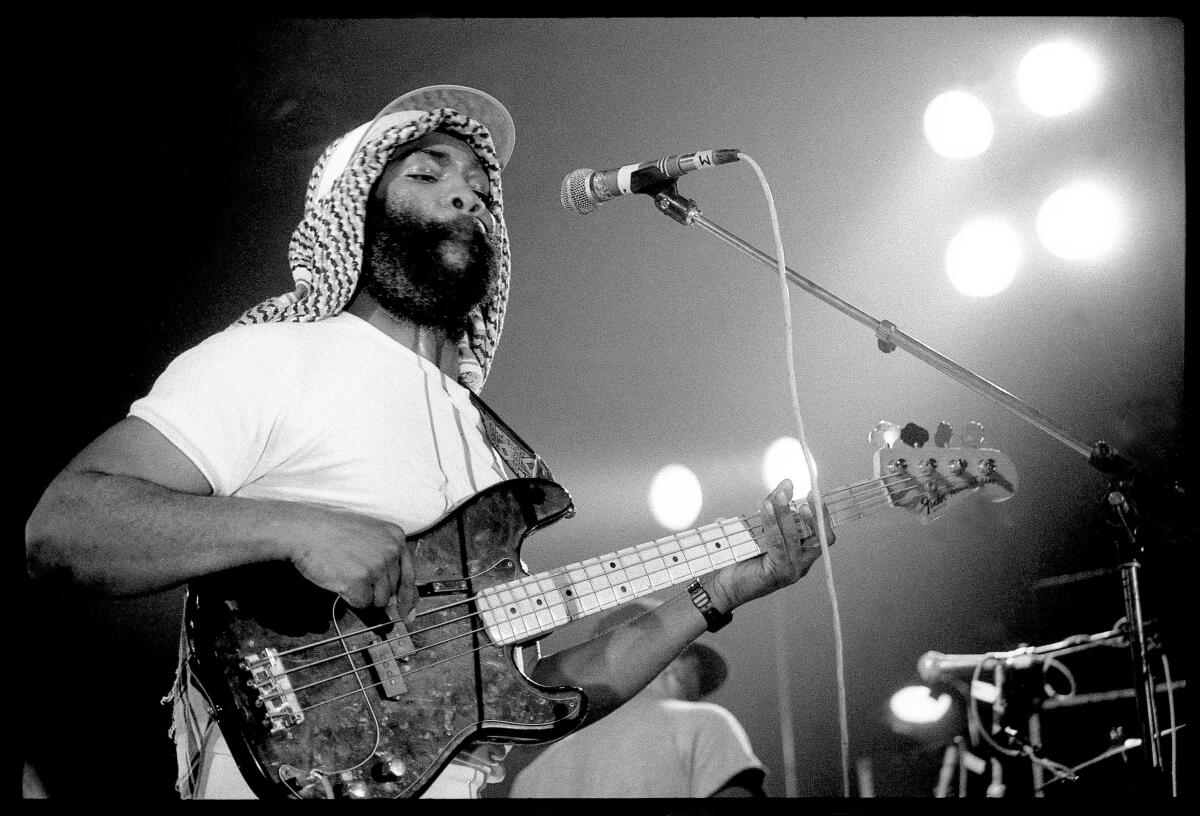

In the crowd, playing the party hosts’ upstairs neighbor, is the man who wrote and produced “Silly Games.” Watching a room full of actors less than half his age sing his song 40 years later, Dennis Bovell was overcome with emotion.

“I was holding back the tears,” says Bovell, a garrulous 67-year-old with seemingly flawless recall of every record he’s ever made. “The song became a kind of spiritual and a kind of protest: the authorities playing silly games with the people. I thought, Steve, how did you see that? I never saw that song as a protest.”

“‘Silly Games’ was in my mind from the get-go,” McQueen says in an email interview. “In many ways, it was the basis for the entire film. It is about intimacy and desire and asking someone to take off their mask.”

The song began with a gimmick. In 1977 Bovell saw a cassette-tape commercial in which Ella Fitzgerald hit a note so high that it shattered a glass. He designed “Silly Games” to peak with such a showstopping note and found in 19-year-old Janet Kay a singer with the range to pull it off. Bovell then developed, with drummer Angus “Drummie Zeb” Gaye, an innovative rhythm that combined reggae with disco, Afrobeat and West African highlife. When “Silly Games” was reissued in June 1979, it reached No. 2 in the U.K. Top 40 and became the defining anthem of lovers rock.

“I knew that every young female from then on would be stood in front of their mirror with their hairbrush, miming that note,” Bovell says. “And it came to pass!”

At the time of the movie’s fictitious party, the real Bovell was one of the U.K.’s busiest producers, with clients including the poet Linton Kwesi Johnson, the post-punk bands the Slits and the Pop Group, the Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto and Franco Rosso, the director of “Babylon,” the first movie to depict the U.K.’s sound system culture. (Sound systems, which originated in Jamaica, are large mobile DJ operations.)

He was also a key player in the activist movement Rock Against Racism, mingling with punk bands such as the Clash. Bovell’s work epitomized multiracial collaboration and solidarity in a time of civil unrest, police brutality and far-right violence.

McQueen describes Bovell as an “incomparable” figure in British music. “He is a person who crossed genres and also invented his own. He is a world of knowledge and a great producer, so therefore a fantastic communicator. He is one of our most valuable Londoners.”

Steve McQueen kicks off his ‘Small Axe’ series with ‘Mangrove,’ a timely true story of protest in London’s West Indian community.

Bovell was born in Barbados in 1953 and moved to England in 1965 to join his father, a bus driver, and mother in South London. While still in his teens, he founded his own reggae group, Matumbi, and sound system, Sufferer, but fell victim to vindictive racist policing, he says.

On Oct. 13, 1974, Bovell was DJing at a soundclash between three rival sound systems in a club in northwest London when a fight broke out between revelers and police. Bovell was falsely accused of getting on the microphone and exhorting the crowd to attack the police. When he turned himself in to the police, figuring that he had nothing to fear, he was accompanied by Rhodan Gordon, the activist played by Nathaniel Martello-White in “Mangrove,” another of McQueen’s “Small Axe” movies.

Until he was arrested, Bovell had been skeptical of friends who claimed to have been framed for crimes they didn’t commit. “Now it was happening to me,” he says. “It was like being launched into some nightmare. It made me know that the police are damn liars.”

During two trials over nine months, most of the police witnesses said that the venue was too dark for them to see clearly, but Bovell says two falsely claimed that it was brightly lit and he was identifiable. “Police officers came and perjured themselves,” he says. “I insisted that they bring a polygraph test into the court and the judge retorted, ‘Do you expect me to believe that police officers lie under oath?’ I said, ‘Mate, bring the polygraph and we’ll find out.’ But he dismissed that.”

Bovell was found guilty and spent six months in jail before he was freed on appeal. The only good thing to come out of his ordeal, he says, was the music he wrote for Matumbi in his cell.

In the early 1970s, the U.K.’s West Indian community was wary of homegrown reggae. “It was always being ridiculed: ‘It doesn’t sound right,’” Bovell says. “I set out to disprove the myth that reggae could not properly be made in the U.K.”

He circumvented this stigma by releasing productions anonymously and stamping large holes in the center of vinyl singles to make them resemble Jamaican imports. One of them, Louisa Mark’s 1975 ballad “Caught You in a Lie,” was embraced by Lloyd Coxsone’s sound system, which prided itself on playing strictly Jamaican music. “It gave me huge confidence to know that I could make reggae in London if they didn’t know it was me,” Bovell says. He then recorded dub reggae incognito under the alias 4th Street Orchestra, with similar success. “It’s not prejudiced by who wrote it or who’s playing on it or where it was recorded. Either you like it or you don’t.” By the time an inquisitive journalist exposed his charade, nobody cared.

In 1976, a Jamaican-born entrepreneur named Dennis Harris sold his corner store and established a studio in Brockley, South London. “He called me up one day and said, ‘I’ve just built the studio, here’s the keys, you’re the engineer,’” Bovell remembers, laughing. “He didn’t ask me, he told me.” Named Lover’s Rock for a song by Augustus Pablo, Harris and Bovell’s label specialized in love songs, sung by women and influenced by American R&B, as an alternative to the overwhelmingly male, stridently political reggae coming out of Jamaica.

“Sound systems had begun [saying] ‘This is lovers rock,’” Bovell says. “That would be telling the audience that this tune is a smooch. This is a chance to get right up close to that guy or girl that you wanted to. That was the name now given to the genre of the music that we in London were making, featuring mainly female singers.”

While lovers rock was apolitical, Bovell was not. In December 1976, Matumbi played the first-ever concert for Rock Against Racism, the grass-roots organization set up in response to a shockingly racist onstage rant by Eric Clapton. “We wanted to form a society that was going to show that everyone in England wasn’t of the same opinion as him,” Bovell says.

In 1978, Bovell struck up an enduring working relationship with Johnson, turning a poet into an international touring artist who decried injustice in stern Jamaican patois over heavy rhythms on tracks such as “Inglan Is a Bitch” and “Fite Dem Back.” “Linton’s poetry is real,” Bovell says. “It’s not ‘Baby, I love you.’ And I felt that I needed to align myself with some of these realities because I had lived through most of them.”

As a producer and remixer, Bovell was sought out by bands who “wanted to play their punk as heavy as reggae was,” recording with artists such as Orange Juice and the Raincoats in the 1980s. He still works with Johnson and remixes artists including Joss Stone and Arcade Fire.

Now Bovell is enjoying the unexpected pleasure of seeing a new generation fall in love with “Silly Games.” Recently, he was standing in a takeaway restaurant when he heard a young woman’s phone play “Silly Games” as a ringtone. “I want to say to her, ‘That’s my song,’” he recalls. “If I said that, she probably wouldn’t believe me.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.