- Share via

The voice seeps in as if from another dimension, hissy and distant, like an AM radio broadcaster transmitting through late-night static.

“‘The Ambassador March’ by Brown’s Orche-streee for the Los Angeles Phonograph Company of Los Angeles, California,” a man announces with a gentlemanly accent. After a moment’s scratchy pause, a violinist opens with a melody, and a small orchestra jumps in. Led by a Long Beach-based bandleader named E.R. Brown, the song dances along for two minutes.

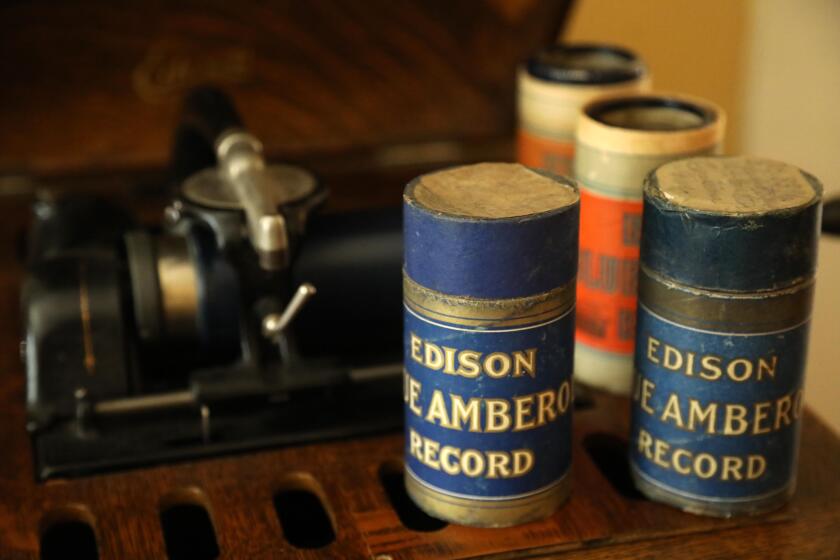

The fidelity is primitive by today’s high-definition audio standards, a quaint toss-away. But “The Ambassador March” and the Coke-can-sized wax cylinder upon which it was etched into permanence in the late 1800s open a portal to another era.

That wax cylinder and others like it — rescued from rural estate sales and dusty attics — have survived earthquakes, heat waves, mold and indifference. They feature Mexican folk songs; military band marches; minstrelsy songs of the kind that preceded American blues, folk and country music; and the voices of former Lincoln cabinet members, Southern senators, popes, preachers and comedians. Their survival is emblematic of a revolution that allowed sound to be freed from its origins. Once untethered, the world would be forever changed.

Many of the recordings have been restored, digitized and added to sound libraries that are easily accessed for free, and they may be the answer to “what do I listen to now?” as we continue to shelter at home or navigate the world cautiously.

These first recordings paved the way for the music industry as we know it today. Columbia Records, which in the late 1890s was known as the Columbia Phonograph Co. and released cylinders of music performed by various minstrel shows, often white men in blackface, remains a music powerhouse whose roster includes Beyoncé, Lil Nas X, Daft Punk, Adele and Tyler, the Creator.

The astounding success of Italian tenor Enrico Caruso was enabled by Victor Talking Machine Co., which came to be under the umbrella of RCA Records, now home to artists such as Miley Cyrus, Childish Gambino and Alicia Keys. Both Columbia and RCA records are now owned by Sony Music Entertainment.

Preserving early recordings — and the lumbering machines that play them — has been an obsession for a small group of Southern California collectors, who have been stealthily wrangling from the wild the essential sounds of the early American acoustic recording era.

Decoding the sound on the wax tubes is a powerful experience — as close to time travel as can be found.

But the clock is ticking.

Not long ago, Dr. Michael Khanchalian sat down in his Monrovia home office to repair an Edison brown wax cylinder, strapping on his nerd glasses — his description — and picking up a probe.

A dentist with his own Pasadena practice, the collector’s vision zoomed in to explore microscopic waves and valleys imprinted onto the delicate tube. Because of their fragility, many brown wax cylinders are considered one-of-a-kind rarities at this point, and he has salvaged hundreds of them using decades-old steel dental instruments.

Khanchalian held the probe above a flame until smoke wafted, then he dipped it into a shallow canister of wax and tapped the sharpened poker onto a crack in the cylinder. Wax rolled like lava through a gully and dried in a few seconds.

“You need it to flow real smoothly into the nooks and crannies,” he said in a whispered tone that suggested Bob Ross painting autumn foliage. The dentist rubbed off excess flecks and polished the surface with a silk cloth.

Many of Khanchalian’s “fixes” have ended up in climate-controlled safety 90 miles north of here at UC Santa Barbara’s renowned cylinder archive. Others are in the British Library and the Library of Congress. On any given evening he might be working to repair a recording of director Cecil B. DeMille’s actor-grandfather, piecing together a broken cylinder of Welsh evangelist Evan Roberts singing hymns, or fixing cracks in a recording by early Black banjo player Charles Asbury.

The home he shares with his wife Janene and two sons is a Dr. Seussian wonderland of early sound machines. Record players or music-making devices line nearly every spot along walls in the living room, their ornate, megaphone-shaped horns jutting out every which way. (Khanchalian, who sports a bushy, Super Mario-esque mustache, parks his Model T in his dad’s garage.)

The dentist has been resurrecting spectral voices on cylinders for decades, a mission he shares with two longtime friends, expert collector John Levin and Oscar-winning sound engineer Mark Ulano. In the 1980s, the trio of obsessives formed what Ulano called “a triangle of engagement” to identify and understand North America’s earliest pop records.

The treasures in UCSB’s Cylinder Audio Archive include recordings of string quartets, spirituals, whistling songs, sermons and politicians who might have been startled to hear the sound of their own voices.

Levin, whose Silver Lake home contains about 3,000 brown wax cylinders, compares their enthusiasm to “people who collect rare books. Cylinders are from this period before there was an industry, and because we can hear it, and see it, and feel it, it’s a wonderful conduit into this early time.”

Among those he and Khanchalian have identified are a previously unknown recording of an early 1890s New Orleans brass band and a tube etched with the sound of composer John Philip Sousa’s New Marine Band.

Levin worked with Ulano, Khanchalian and Dan Reed of the Antique Phonograph Society for years to restore and digitize the Southwest’s most important collection of wax cylinders, the recordings of librarian, writer and onetime Los Angeles Times reporter Charles Lummis.

A socially-connected renaissance man, Lummis bought an Edison recorder in 1902 and over the next three years recorded more than 450 cylinders, capturing a host of regional musicians, intellectuals and personalities in and around his Mount Washington home. He preserved Mexican folk songs and original compositions played by musicians including Doña Adalaida Kamp, José de la Rosa, the Villa Family and Manuela Garcia.

“We joke with each other about being brown-wax brothers,” Khanchalian says of Levin. “We’ve learned so much together, and we both hope we can get some of this information down before it’s too late.”

Levin has mined collections the world over, amassing a singularly significant archive of early sound recordings, most of which pre-date the Lummis cylinders.

Among his holdings are a volume of crucial operatic recordings made by Gianni Bettini, an audiophile-inventor based in New York; more than 400 releases by the United States Phonograph Co., an early label based in New Jersey that issued cylinders by many “first generation” recording artists; and a wide range of cylinders from America’s oldest-known regional record labels — Lambert, the Kansas City Talking Machine Co., Potter and Earle Electricians, Siegel-Myers, and the United States Phonograph Co. among them.

A semi-retired creative director of a digital marketing agency, in recent years Levin has invested his time and energy into designing and commissioning one of the most technically advanced cylinder players ever built. Called the CPS-1, it digitizes the sound waves via a specially designed cartridge and stylus that can read parts that primitive needles could never amplify, adding more nuance to the static-y and crackly recordings. Since the cylinder player and digitizer went on the market a few years ago, Levin has sold nine of them — at about $20,000 a pop.

“There’s a really interesting confluence right now of a lot of knowledge about analog technology, some rich digital tools that weren’t there 10 years ago and a robust internet that wasn’t there 15 years ago,” Levin says. “This is a very important period.”

Ulano, the son of legendary jazz drummer and educator Sam “Mr. Rhythm” Ulano, has served as Quentin Tarantino’s production sound mixer on every movie since 1997’s “Jackie Brown.” Last year, he was nominated for a sound mixing Oscar for his work on Tarantino’s “Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood.” (He was also nominated in the same category for his work on James Gray’s “Ad Astra.”) In 1998, Ulano won an Oscar for his sound work on “Titanic.”

A scholar on the history of film and audio recording, he describes Levin and Khanchalian’s efforts as crucial to understanding “the early stages of mass media and commercializing of music and spoken word as a commodity.”

“There’s a magic to the vitality of hearing humans speak and sing and communicate” on such ancient recordings, Ulano said. “Even the private home recordings, to me, are among the most fascinating because they’ve captured the living dynamic of people in the flow and in play in a very organic way.”

Levin is drawn to the recordings for their mystery.

Not long ago, for example, Levin bought two unmarked brown wax cylinders from a picker he knew in the Midwest. Evidence suggested that whoever owned them at one point lived in downtown Los Angeles. When Levin played the cylinders, he was shocked to hear the announcer identify the recordings as being from “the Los Angeles Phonograph Co.” No such business was known to exist. Levin and Khanchalian believe the two cylinders to be the first known commercial recordings to be made and marketed in Los Angeles — and issued by the city’s first record label.

Is the birth of the Los Angeles recording industry nestled in the grooves of these newly discovered wax cylinders?

Khanchalian’s interest in early recordings and devices started in childhood. He had an aunt who was obsessed with antiques, and on her sprees she’d buy him curious objects, hand them to him and tell him to figure out what they were. One time she presented him a cylinder and he was hooked.

When he was a teenager, his younger sister accidentally broke a couple of his favorite recordings. They were irreplaceable, so he decided to try to fix them. His solution, he said with a chuckle, was “to learn all the ways it can’t be done.” Decades later, he’s the go-to guy in the country on all the ways it can.

He paused for a moment when asked who his peers were in the cylinder repair business, before coming up blank. “No one.”

Although Khanchalian’s dentistry-informed methods, unorthodox as they are, have earned him work for respected institutions, the techniques would likely not pass muster with most libraries, which typically require advanced degrees in the field. Recorded sound has long been treated as an afterthought by archivists, most of whom specialize in books, transcripts, paintings, photographs or film footage. As a result, cylinder restoration techniques have never been standardized, says David Seubert, curator for the Performing Arts Collection at UC Santa Barbara Library. He heads the university’s Cylinder Audio Archive.

“We rely on people like Mike,” Seubert said, “who have developed, basically, folk knowledge about how to fix this kind of stuff.”

Located in a wing of the university library, the archive’s collection of arcane music and machines, stored in a climate-controlled, purpose-built facility to hold wax cylinders and 78 rpm records, is the most extensive on the West Coast.

Lined in rows of drawered cabinets and towering, movable shelving units, the archive’s quantity of cylinders and discs overwhelms the imagination. Say what you want about the millions of digital songs stored in the cloud and awaiting your Spotify spin; the sensation of standing in a room teeming with some of the world’s earliest sounds feels somehow even more remarkable than any celestial jukebox.

Collectors like Levin and Khanchalian make it possible for Seubert to present to the public recordings that would otherwise remain unheard to all but a chosen few.

Though hardly as sophisticated as Apple Music or Spotify, the UCSB Cylinder Audio Archive portal features a searchable database that accesses more than 10,000 cylinders stored in the facility’s basement. The portal is divided into dozens of categories including hymns, corridos, comic songs, ethnic humor, speeches, sermons, waltzes and yodeling songs, which combine to offer a perspective-shifting listen into the spirit, expressions and dialects that typified the era.

Pockets of the archive also lay bare in brutal detail the racism that permeated American culture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. An hour of browsing through the minstrel music will shine a direct beam on sinister tropes and casual references to nooses and lynching that typified the so-called blackface music of the period.

Another part of the collection gathers more than 650 home wax recordings made in private residences as audio letters, to document birthdays or simply to pass the time.

That public-facing charter drew Levin to hook up with Seubert and the university. During their initial meetings in the early ‘00s, Levin told him that donating items from his collection would be contingent on making the recordings accessible to the public. Seubert was headed in the same direction.

Levin then confesses to what he calls “a little bit of a hidden agenda, which is to make it as difficult as possible for the university to ever dismantle what [Seubert’s] created up there.” It also affords him access to a library’s worth of archaic recordings.

Cylinder collectors come in a few different varieties, Ulano says. “Some collect out of compulsion. Some of them are out of academic passion for documenting. Some are in it for the fun of it, and you’ll see permutations of all that.” Levin is the kind who, when deciding to ride out the pandemic with his wife Pat at their Connecticut home, packed his bulky CPS-1 machine and 100 cylinders into their car for the cross-country road trip so that he could work on his various projects while in shutdown.

Khanchalian describes a cycle that many such hobbyists will understand: “When no one else can answer the questions and you start doing the primary research, the fascination keeps growing. Suddenly people start coming to you for information, and then you become the go-to guy.”

How we got the story: The amateur archivists who are saving the world’s oldest sounds.

But none of these guys — yes, cylinder collectors are mostly men — is getting any younger. The whole endeavor’s incredibly impractical, and that’s a problem. Curious kids who in previous generations would get lost in collecting and documenting the past are more likely spending off-hours building virtual spaces in “Minecraft” than tinkering with anachronistic tech or wondering how songs such as R.I. Jose’s “Poor Blind Boy” or Dan Quinn’s “Still His Whiskers Grew” came to be.

Unlike the online realm, there aren’t any backups of the brown wax cylinders dotting flea markets, antique malls and old storage sheds across America. Each is its own would-be Rembrandt.

“I just try to sweep the stuff up,” Levin says.

He has cylinders that he’s never heard because they’re too fragile for playback. “They need a kind of treatment that hasn’t been developed yet,” he said. “But it’s astonishing how much this early technology captured that we can still go in there and get.”

The problem now is one of attention, adds Levin, “and that is what we are in danger of losing as all of these old analog guys time out.” As the phonograph collecting community dwindles and interest wanes, who continues the search?

What good’s a rescued cylinder, after all, if no one can conjure the magic within it?

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.