‘He’s our Satan’: Mega music manager Irving Azoff, still feared, still fighting

- Share via

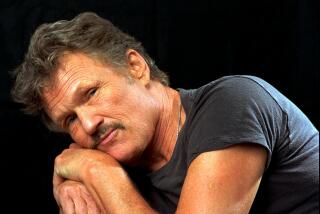

PEBBLE BEACH, Calif. — This is not Irving Azoff’s house. Irving and his wife Shelli own houses all over, from Beverly Hills to Cabo San Lucas, but right now in the last week of October it’s too cold at the ranch in Idaho and too hot at the spread in La Quinta, so he’s renting this place — a modest midcentury six-bedroom that sold for $5 million back in 2016.

From the front door you can see all the way out, to where Arrowhead Point juts like the tail of a comma into the calm afternoon waters of Carmel Bay. More importantly, the house is literally across the street from the Pebble Beach Golf Links, where Azoff likes to play with his college buddy John Baruck, who started out in the music business around the same time Azoff did, in the late ’60s, and just retired after managing Journey through 20 years and two or three lead singers, depending how you count.

For the record:

11:29 a.m. Nov. 6, 2020An earlier version of this post said Irving Azoff and Jon Landau are the first living managers inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. They are the first active managers so honored.

Azoff is 72, and this weekend he’ll be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame alongside Bruce Springsteen’s longtime manager Jon Landau. Beatles manager Brian Epstein and Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham are already in, but Azoff and Landau are the first active managers thus honored. As a partner in Full Stop Management — alongside Jeffrey Azoff, his oldest son and the third of his four children — he steers the careers of clients like the Eagles, Steely Dan, Bon Jovi and comedian Chelsea Handler, and consults when needed on the business of Harry Styles, Lizzo, John Mayer, Roddy Ricch, Anderson .Paak and Maroon 5. Azoff has Zoom calls at 7, 8 and 9 tomorrow morning, and only after that will he squeeze in a round.

The work never stops when you view the job the way Azoff does, as falling somewhere between consigliere and concierge. “My calls can be everything from ‘My knee buckled, I need a doctor’ to ‘My kid’s in jail,’” Azoff says. “I mean, you have no idea. The ‘My kid’s in jail’ one was a funny one, because the artist then said to me, ‘Y’know, I’ve thought about this. Maybe we should leave him there for a while.’”

Whether Trump or Biden wins, difficult repair works lies ahead after election 2020. Can we bridge our cultural divide?

Golf entered Azoff’s life the way a lot of things have — via the Eagles, whom Azoff has managed since the early ’70s. Specifically, Azoff took up golf in the company of the late Glenn Frey, the jockiest Eagle, the one the other Eagles used to call “Sportacus.” By the time the Eagles returned to the road in the ’90s they’d left their debauched ’70s lifestyles largely behind, but Azoff and Frey got hooked on the little white ball.

“Frey would insist on booking the tour around where he wanted to play golf,” Azoff says. “We made Henley crazy. Henley would call me in my room and he’d go, ‘Why the f— are we in a hotel in Hilton Head North Carolina and starting a tour in Charlotte? Is this a f— golf tour?’”

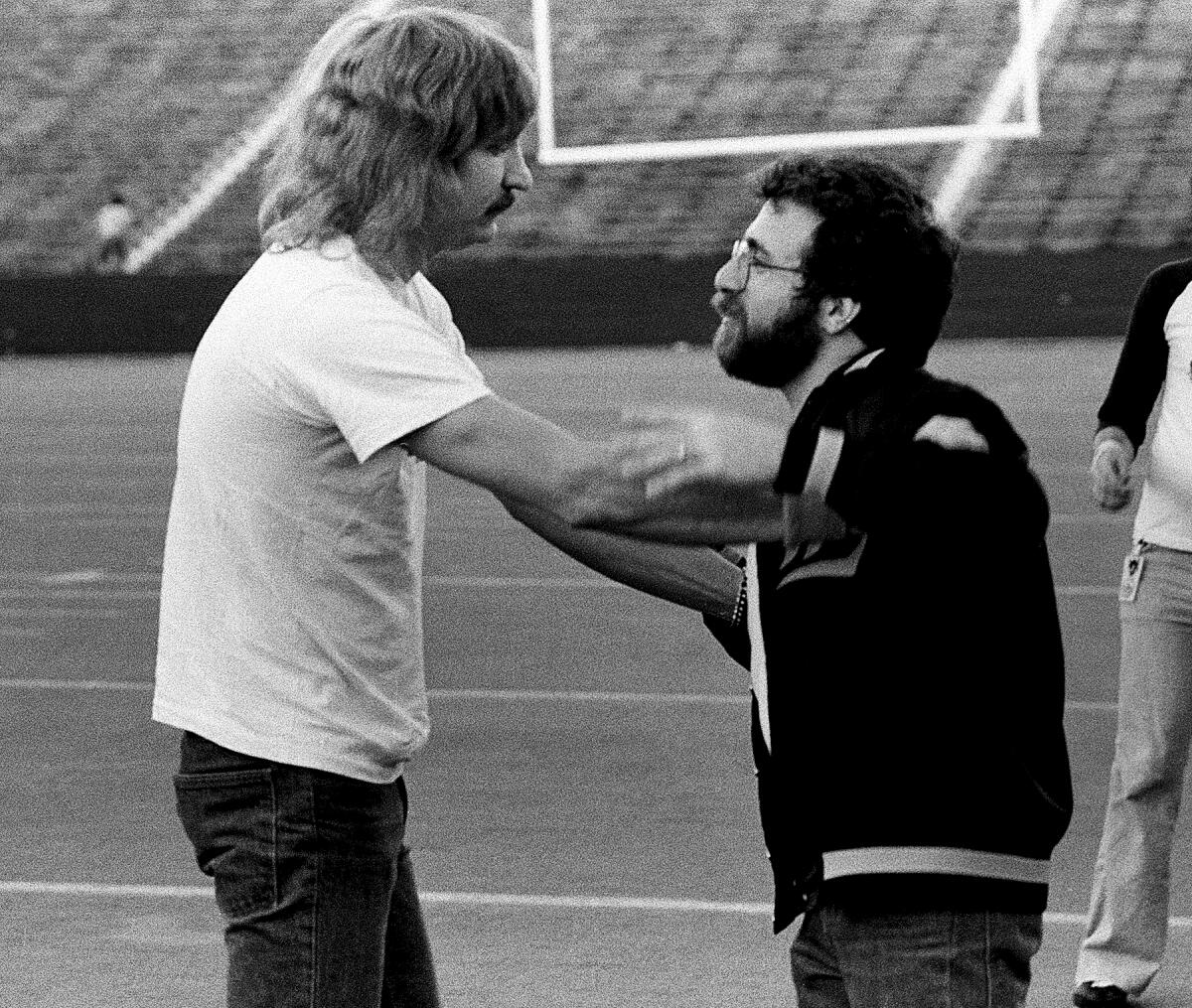

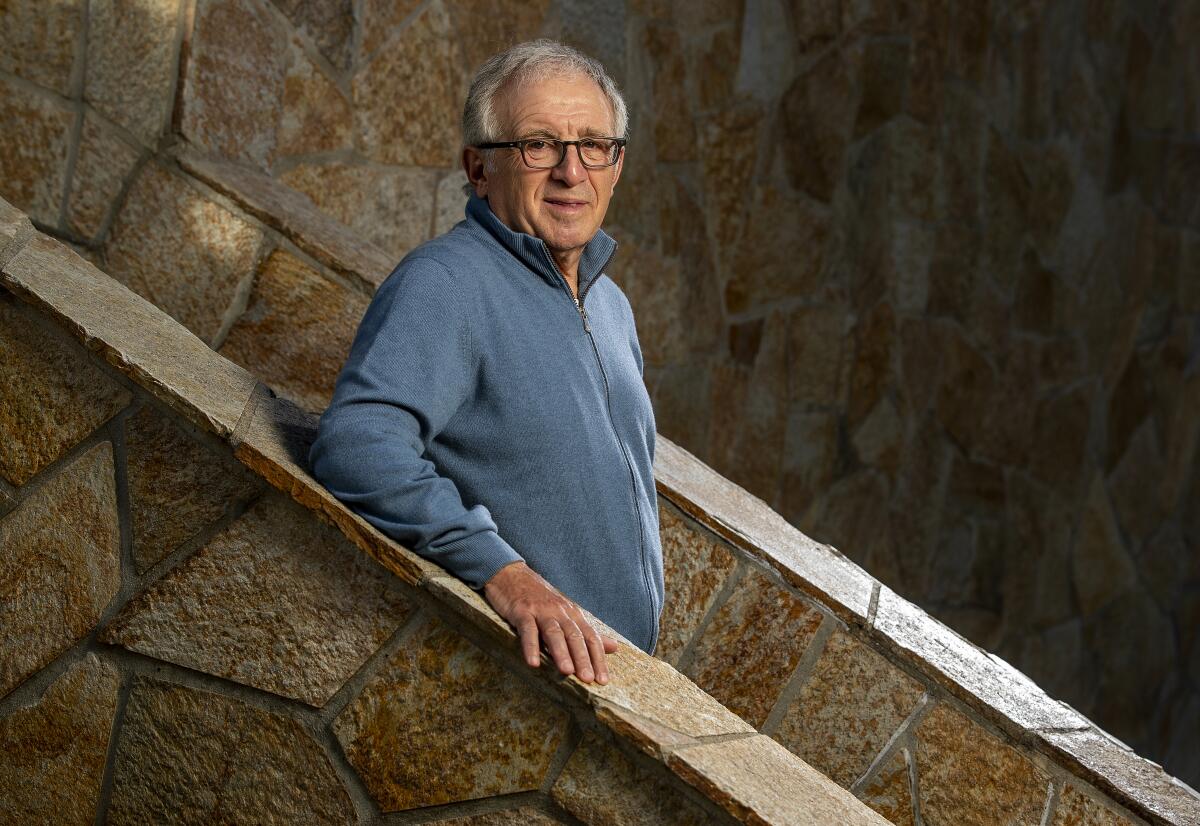

Trailed by Larry Solters, the Eagles’ preternaturally dour minister of information, Azoff makes his way down the hill from the house for dinner at the golf club’s restaurant. He’s only 5 feet, 3 inches, a diminutive Sydney Pollack in jeans and a zip-up sweater. In photos from the ’70s — when he was considerably less professorial in comportment, a hipster exec with a spring-loaded middle finger — he sports a beard and a helmet of curly hair and mischievous eyes behind his shades, and looks a little like a Muppet who might scream at Kermit over Dr. Teeth’s appearance fee.

His father was a pharmacist and his mother was a bookkeeper. He grew up in Danville, Ill., booked his first shows in high school to pay for college, dropped out of college to run a small Midwestern concert-booking empire and manage local acts such as folk singer Dan Fogelberg and heartland rock band REO Speedwagon. Los Angeles soon beckoned. He met the Eagles while working for David Geffen and Elliot Roberts’ management company and followed the band out the door when they left the Geffen fold; they became the cornerstone of his empire. “I got my swagger from Glenn Frey and Don Henley,” he says. “No doubt about it.”

Azoff never took to pot or coke. The Eagles lived life in the fast lane; he was the designated driver. “Artists,” he once observed, “like knowing the guy flying the plane is sober.” This didn’t stop him from trashing his share of hotel rooms, frequently with guitarist Joe Walsh — whose solo career Azoff shepherded before Walsh joined the Eagles, and who was very much not sober at this time — as an accomplice.

“This was a different age,” Walsh says of his time as the band’s premier lodging-deconstructionist. “We could do anything we wanted, so we did. And Irving’s role was to keep us out of prison, basically.” He recalls a pleasant evening in Chicago in the company of John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd, which culminated in Walsh laying waste to a suite at the Astor Towers hotel that turned out to be the owner’s private apartment. “We had to check out with a lawyer and a construction foreman,” Walsh remembers. “But Irving took care of it. Without Irving, I’d still be in Chicago.”

Azoff became even more infamous for the pit bull brio he brought to business negotiations on behalf of the Eagles and others, including Stevie Nicks and Boz Scaggs. He didn’t seem to care if people liked him, and his artists loved him for that. Steely Dan co-founder Walter Becker said they’d hired Azoff because he “impressed us with his taste for the jugular … and his bizarre spirit.” Jimmy Buffett’s wife grabbed him outside a show at Madison Square Garden, pushed him into the back of a limo and said, You have to manage Jimmy, although Buffett already had a manager at the time.

His outsized reputation as an advocate not just willing but eager to scorch earth on behalf of his clients became an advertisement for his services, a phenomenon that continues to this day. In August 2018, Azoff’s then-client Travis Scott released “Astroworld,” which debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200 chart, and occupied that slot again the following week, causing Nicki Minaj’s album “Queen” to debut at No. 2. On her Beats One show “Queen Radio,” Minaj accused Scott of gaming Billboard’s chart methodology to keep her out of the top slot and singled his manager out by name: “C—sucker of the Day award,” she said, “goes to Irving Azoff.” Azoff says he reacted as only Azoff would: “I said, ‘I’m really unhappy about that. I want to be c—sucker of the year.’” In 2019, Minaj hired Azoff as her new manager.

Most of the best things anyone’s ever said about Azoff are statements a man of less-bizarre spirit would take as an insult. When the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inducted the Eagles in 1998, Don Henley stood onstage and said of Azoff, “He may be Satan, but he’s our Satan.”

An N95-masked Azoff takes a seat on a patio with a view of hallowed ground — the first hole of the Pebble Beach course, a dogleg-right par 4 with a priceless view of the bay. He cheerfully admits that he and his partners at Full Stop are “obviously, as a management business, kind of losing our ass” this year due to COVID-19. In another reality, the Eagles would have played Wembley Stadium in August before heading off to Australia or the Far East. Styles would have just finished 34 dates in the U.S., Canada and Mexico. As it stands Azoff is hearing encouraging things about treatments and vaccines and new testing machines, and is reasonably confident that technology will soon make it possible for certified-COVID-free fans to again enjoy carefree evenings of live music together; he doesn’t expect much to happen in the meantime.

“What are you gonna do,” Azoff says, “take an act that used to sell 15,000 seats and tell them to play to 4,000 in the [same] arena? The vibe would be horrible, and production costs will stay the same.”

He knows of at least six companies trying to monetize new concert-esque experiences — pay-per-view shows from houses and soundstages, drive-in events and so on. But he’s not convinced anybody wants to sit in their parked car to watch a band play. More to the point, he’s not convinced it’s rock ’n’ roll.

“Fallon and Kimmel, all these virtual performances — people are sick of that,” he says. “Your production values from home aren’t that good. And they’re destroying the mystique. I mean, Justin Bieber jumping around on ‘Saturday Night Live’ the other night without a band, and then he had Chance the Rapper come out? It made him look to me, mortal. I didn’t feel any magic. So we’ve kinda been turning that stuff down to just wait it out.”

In the meantime, he says, Full Stop is picking up new clients during the pandemic. Artists with time on their hands, he believes, “have taken a hard look at their careers— so we’ve grown. No revenues,” he adds with a chuckle, “but people are saying, ‘We need you, we need to plan our lives.’”

“IN HIGH SCHOOL,” Jeffrey Azoff says, “I wanted to be a professional golfer, which has obviously eluded me.” He never expected to take up his father’s profession. “But my dad has always loved his job so much. There’s no way that doesn’t rub off on you.”

The younger Azoff got his first industry job at 21, as a “glorified intern” working for Maroon 5’s then-manager Jordan Feldstein. After a week of filing and fetching coffee, he called his father and complained that he was bored. According to Jeffrey, Irving responded, “Listen carefully, because I’m going to say this one time. You have a phone and you have my last name. If you can’t figure it out, you’re not my son.”

“Direct quote,” Jeffrey says. “It’s one of my favorite things he’s ever said to me. And it’s the spirit of the music business, by the way. There are no rules to this. Just figure it out.”

Over dinner I keep asking Irving how he got the temerity, as a kid barely out of college, to plunge into the shark-infested waters of the ‘70s record industry in Los Angeles. He just shrugs.

“I never felt the music business was that competitive,” he says. “It’s just not that f—ing hard. I don’t think there’s that many smart people in our business.”

It’s been written, I say, that once you landed in California and sized up the competition, you called John Baruck back in Illinois and said —

“We can take this town,” Azoff says, finishing the sentence. “Where’d you get that? John told that story to [Apple senior vice president] Eddy Cue on the golf course three days ago. It’s true. I called John up and said, ‘OK, get your ass out here. We can take this town.’”

In the ensuing years, Azoff has occupied nearly every high-level position the music industry has to offer, surfing waves of industry consolidation. He’s been the president of a major label, MCA; the CEO of Ticketmaster; and executive chairman of Live Nation Entertainment, the behemoth formed from Ticketmaster’s merger with Live Nation. In 2013 he and Cablevision Systems Corp. CEO and New York Knicks owner James Dolan formed a partnership, Azoff MSG Entertainment; Azoff ran the Forum in Inglewood for Dolan after MSG purchased it in 2012.

Earlier this year Dolan sold the Forum for $400 million to former Microsoft CEO and Clippers owner Steve Ballmer, who’s since announced plans to build a new stadium on a site just one mile away. Despite the apocalyptic parking scenario that looms for the area — two stadiums and a concert arena on a one-mile stretch of South Prairie Boulevard — Azoff is confident that the Forum will live on as a live-music venue. “People are going, ‘They’re going to tear it down’ — they’re not going to tear it down,” Azoff says. “It’s going to be in great hands. I have many of the artists we represent booked in the Forum, waiting for the restart based on COVID.”

The holdings of the Azoff Co. — formed when Dolan sold his interest in Azoff MSG back to Azoff two years ago — include Full Stop, the performance-rights organization Global Music Rights and the Oak View Group, which is developing arenas in Seattle and Belmont, N.Y., and a 15,000-seat venue on the University of Texas campus in Austin. Azoff describes himself as increasingly focused on “diversification, and building assets for the family that aren’t just dependent on commissions, shall we say.”

But as both a manager and a co-founder of a lobbying group, the Music Artists Coalition, he’s also devoting more time and energy to a broad range of artists’-rights issues, from health insurance to royalty rates to copyright reversion to this year’s Assembly Bill 5, which threatened musicians’ independent-contractor status until it was amended in September. (“That was us,” Azoff says, somewhat grandly. “I got to the governor, the governor signed it — Newsom was great on it.”) He describes his advocacy for artists — even those he doesn’t manage — as a “war on all fronts,” and estimates there are 21 major issues on which “we’ve sort of appointed ourselves as guardians.”

He does not continue to manage artists because he needs the money, he says. (As the singer-songwriter and Azoff client J.D. Souther famously put it, “Irving’s 15% of everybody turned out to be more than everyone’s 85% of themselves.”) Everything he’s doing now — building clout through the Azoff Co., even accepting the Hall of Fame honor — is ultimately about positioning himself to better fight these fights. “I’d rather work on [these things] than anything else,” he says. “But if I didn’t have the power base in the management business, I couldn’t be effective.”

The recorded music industry, having fully transitioned to a digital-first business, is once again making money hand over fist, he points out, but even less of that money is trickling down to artists. That imbalance long predates Big Tech’s involvement in the field, but the failure of music-driven tech companies to properly compensate musicians is clearly the largest burr under Azoff’s saddle.

“These people, when they start out — whether it’s Facebook, Snapchat, TikTok, whatever — they resist paying for music until you go beat the f— out of them. And then of course, none of them pay fair market value and they get away with it. Your company’s worth $30 billion and you can’t spend 20 grand for a song that becomes a phenomenon on your channel? Even when they pay, artists don’t get enough. Writers don’t get enough. Music, as a commodity, is more important than it’s ever been, and more unfairly monetized for the creators. And that’s what creates an opportunity for people like me.”

AZOFF’S FIRM NO longer handles Travis Scott, by the way. “Travis is unmanageable,” Azoff says, nonchalantly and without rancor. “We’re involved in his touring as an advisor to Live Nation, but he’s calling his own shots these days.”

I ask if, in the age of the viral hit and the bedroom producer, he finds himself running into more artists who assume they don’t need a manager. Ehh, Azoff says, like it’s always been that way. “There’s a lot of headstrong artists,” he says. “I haven’t seen one that’s better off without a manager than with,” he says, and laughs a little Dennis the Menace laugh.

We’re back at the house. Azoff takes a seat on the living-room couch; Larry Solters sits across from him, his back to the sea. Azoff recalls another big client. Declines to name him. Says he was never happy, even after Azoff and his people got him everything on his wish list. “He hit me with a couple bad emails. Just really disrespectful s—. I sent him an email back that said, ‘Lucky for me, you need me more than I need you. Goodbye.’”

He will confirm having resigned the accounts of noted divas Mariah Carey and Axl Rose. Reports that he once attempted to manage Kanye West have been greatly exaggerated, he says, although they’ve spoken about business. “Robert [Kardashian] was a good friend of mine. The kids all went to school together,” Azoff says. “What I always said to Kanye was, you’re unmanageable, but we can give you advice.

“A lot of people could have made a dynasty on the people we used to manage,” Azoff says, “let alone the ones we kept.”

In song after song on her very horny new album, “Positions,” Grande exults in the intimate possibilities of a quiet night (or 200) in quarantine.

But he still works with many artists who joined him in the ’70s — with Henley, with Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen and with Joe Walsh. Walsh has been sober for more than 25 years; it was Azoff, along with Henley and Frey, who talked him into rehab before the Eagles’ 1994 reunion tour. “Irving never passed judgment on me,” Walsh says. “And from that meeting on, he made sure I had what I needed to stay sober.” If he hadn’t, Walsh says, there’s no chance we’d be having this conversation. “All the guys I ran with are dead. Keith Moon’s dead. John Entwistle’s dead. Everybody’s dead, and I’m here. That’s profound to me.”

The first client Azoff lost was Minnie Riperton — in 1979, to breast cancer when she was only 31. Then Warren Zevon, to cancer, in 2003. Fogelberg, to cancer, four years later.

“And then Glenn,” says Azoff, referring to the Eagles co-founder who died in 2016. “I miss Glenn a lot. And now Eddie.”

Van Halen, that is. I ask Azoff if he can tell me a story that sums up what kind of guy Eddie Van Halen was; he tells me a beautiful one, then says he’d prefer not to see it in print. It makes perfect Azoffian sense — profane trash talk on the record, tenderness on background.

I ask if he’s been moved to contemplate his own mortality, as his boomer-aged clients approach an actuarial event horizon. Of course the answer turns out to involve keeping pace with an Eagle.

“Henley and I are having a race,” he says. “Neither one of us has given in. Neither one of us is going to retire.”

Henley was born in July 1947; Azoff came along that December. Does Don plan to keep going, I ask, until the wheels fall off?

“I don’t know,” Azoff says.

Do you ever talk about it?

“Yeah! He’ll call me up and he’ll go, ‘I really feel s— today.’ And I say, ‘Well, you should, Grandpa. You’re an old man. You ready to throw in the towel? Nope? OK.’”

Azoff says, “I contend that what keeps us all young is staying in the business. I’ve had more people tell me, ‘My father, he quit working, and then his health started failing,’ and all that. Every single — I mean, every single rock star I know is basically doing it to try and stay young. And I think it works. I really think it works.

“I have this friend,” Azoff says. “Calls me once a week, he’s sending me tapes, it’s his next big record. Paul Anka! He’s 80 years old. OK? And my other friend, Frankie Valli …”

“Do you know how old Frankie Valli is?” Solters says. “Eighty-six. And he still performs.”

“Not during COVID,” Azoff says. “I told the motherf—, ‘You’re not going out.’”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.