Commentary: It’s time to cancel ‘The Star-Spangled Banner.’ Here’s what should replace it

- Share via

The Francis Scott Key monument in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park is one of those old-fashioned pieces of public art that, shall we say, lays it on thick. It is imposing and fussy, a 52-foot-tall chunk of travertine and marble loaded up with classical trimmings. There’s a fluted colonnade, four eagles with majestically fanned-out wings, swags and stars, and, at the very top of the big pile, the figure of Columbia, the traditional female personification of the United States, clutching an American flag.

In the center of the monument is the main attraction, a bronze statue of Key, the Washington, D.C., lawyer who, 206 years ago, wrote the words to “The Star-Spangled Banner” to commemorate the American victory in the Battle of Baltimore, in the War of 1812. Key is captured in a heroic pose: enthroned on a big chair with pen in hand, looking every inch the sort of poetaster who would come up with lines like “O’er the ramparts we watched / Were so gallantly streaming.”

At least this is how the monument used to appear. Today, Francis Scott Key is no longer in Golden Gate Park. On June 20, protesters lassoed the statue with ropes, heaved and hoed, and down came Key, somersaulting off the pediment, head o’er heels. Key was a slave owner, like many of the historical personages whose statues have been defaced and destroyed in the Black Lives Matter uprising that followed the May 25 killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police. But it was also Key’s role as a songwriter — his famous ode to the land of the free and the home of the brave — that made him a target for protesters.

“The Star-Spangled Banner” had been a fixture of American life for more than a century prior to May 4, 1931, when President Hoover signed a bill establishing the song as the national anthem. The tradition of playing the song prior to sporting events dates to World War II; after the war, NFL commissioner Elmer Layden formalized the practice, declaring “the playing of the national anthem should be as much a part of every game as the kickoff.” This custom has of course become a flash point in the culture wars in recent years, since the 2016 NFL preseason, when San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick refused to stand for the playing of the song. Kaepernick pointed out that he was making a statement about racial injustice, not protesting the “The Star-Spangled Banner” itself. But now, it seems, the wave of reckoning and revisionism that is sweeping the country may have come for the national anthem.

Highland Park has long been the heart of L.A.’s musical bohemia, home to Chicano punk and Billie Eilish. Now, COVID-19 threatens the scene’s very existence.

In the days that followed the toppling of the Golden Gate Park statue, viral posts on social media decried “The Star-Spangled Banner” as a racist song. Major League Soccer announced that the anthem would not be played before games when its season resumed in July following the coronavirus lockdown. A high school junior in New York City made news by refusing to record the song for her school’s socially distanced “virtual graduation.” A petition posted on Change.org advocated dropping the song as the national anthem, pointing to “elitist, sexist, and racist” verses in Key’s poem, “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” from which “The Star-Spangled Banner” was adapted. The poem, written by Key on Sept. 14, 1814, after he witnessed the bombardment of an American fort by British ships in Baltimore Harbor, includes the lines: “No refuge could save the hireling and slave/From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave.”

Scholars disagree about the meaning of this couplet. Some read the words as a reference to escaped slaves fighting alongside the British, who promised to grant freedom to Black soldiers in exchange for their service. Historian Jason Johnson has called “The Star-Spangled Banner” “a diss track to Black people who had the audacity to fight for their freedom.” Marc Ferris, the author of “Star-Spangled Banner: The Unlikely Story of America’s National Anthem,” has written that Key was likely using the term “slave” more loosely, to describe “all of the monarch’s loyal subjects, including British troops — as contrasted with free patriot Americans.” Others argue that this context is academic: The only part of the poem that anyone knows, that anyone ever sings, is the first stanza, the one that begins “O say, can you see.”

But there are also arguments against “The Star-Spangled Banner” on aesthetic grounds, criticisms that have dogged the anthem for decades. For one thing, it’s not an especially American song. Its lyrics are ornate and Anglophile, with syntax that frustrates the efforts of normal human Americans to follow along — to deduce who or what, exactly, is gleaming and streaming.

As for the music: It’s as British as beef Wellington. Key’s poem was set to “To Anacreon in Heaven,” the anthem of a London gentleman’s club, composed by John Stafford Smith sometime in the late 1760s or early 1770s. The result is a tune that is charmless and difficult to sing, which meanders through wan melodic passages en route to a big climactic cry — the money-shot high note on “O’er the land of the freeeeee” — that defeats 99% of vocalists who attempt it.

“It’s a terrible piece of music,” said Frank Sinatra in 1969. “If you took a poll among singers, it would lose a hundred to nothing.”

A song with words few people understand, which fewer can sing, whose sound and spirit bear no relation to our catchy, witty, unpretentious homegrown musical forms: Is this really what we want to hear when we “rise to honor America”?

In recent weeks, suggestions for alternative national anthems have circulated online. The writer and critic Kevin Powell proposed John Lennon’s “Imagine.” (Powell called it “the most beautiful, unifying, all-people, all-backgrounds-together kind of song you could have.”) “Imagine” is less stodgy than “The Star-Spangled Banner,” but it’s no less British, and I’m not sure that its drippy utopianism — a multi-millionaire’s daydream of a world with “no possessions” — strikes the apt note.

Then there are the usual suspects, from the canon of American civic-secular hymns. “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” the poem written in 1900 by the Black writer and activist James Weldon Johnson and set to music five years later by his brother J. Rosamond Johnson, has an impeccable pedigree and centers the Black experience in the national story. (The Undefeated website reported that the song will be performed before each game during the opening week of the season.) But like “The Star-Spangled Banner” — like, for that matter, “America the Beautiful” — “Lift Every Voice” is out of step with the 21st century, with a prim melody redolent of Victorian light opera and a lyric sheet full of antiquated poesy. Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America” has more vernacular punch, but its uncomplicated patriotism (“God bless America / Land that I love / Stand beside her / And guide her”) doesn’t wash in 2020. “This Land Is Your Land,” written in 1940 by Woody Guthrie as a response to “God Bless America,” is a favorite of many who lean left. Yet Guthrie’s song has its own blind spots: to indigenous Americans, the refrain “This land belongs to you and me” may sound less like an egalitarian vision than a settler-colonialist manifesto.

Nope, none of these songs will do. At a moment when the United States is in the grip of multiple crises — convulsed by debates over racism and injustice, ravaged by a pandemic, with a crumbling economy and a faltering democracy — the very idea of a national anthem, a hymn to the glory of country, feels like a crude relic, another monument that may warrant tearing down. But if we must have an anthem, it should be far different than the one we’ve got now, positing another kind of patriotism, an alternative idea of America and Americanness. It would also be neat if it was, you know, a decent song, which a citizen could sing without crashing into an o’er or a thee, or being asked to pole vault across octaves.

In fact, there is such a song. The song is “Lean on Me.”

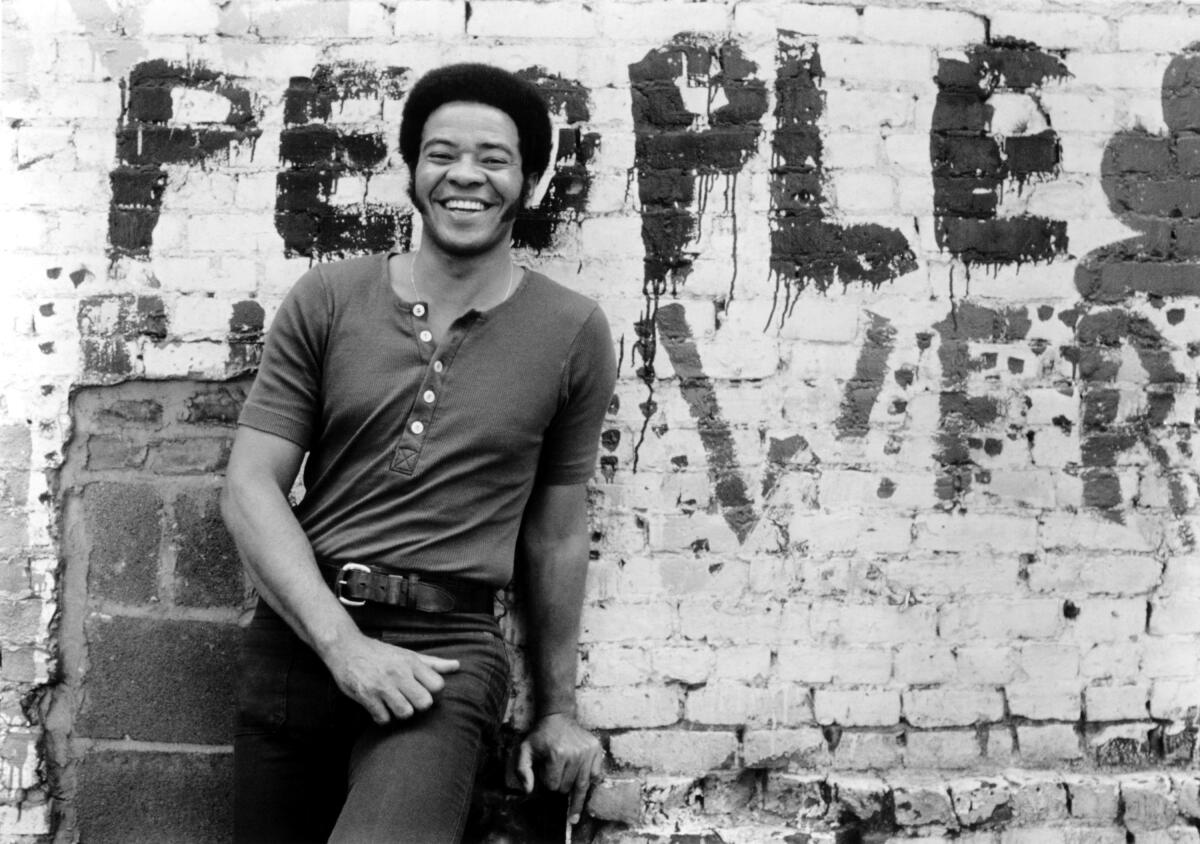

Bill Withers’ 1972 soul ballad may seem like a curious choice. It has none of the qualities we associate with national anthems. It’s a modest song that puts on no airs. It speaks in plain musical language, without a trace of bombast, in a tidy arrangement that unfolds over a few basic chords. It doesn’t march to a martial beat or rise to grand crescendos. The lyrics hold no pastoral images of fruited plains or oceans white with foam, no high-minded invocations of liberty or God. “Lean on Me” is a deeply American song — but it’s not, explicitly at least, a song about America.

Yet it has long been a kind of national anthem. “Lean on Me” is one of just a handful of songs to have reached No. 1 on the Billboard pop charts in two different versions. (Withers’ original hit No. 1 in 1972; 15 years later, Club Nouveau took a spunky electro-R&B version to the top of the Hot 100.) It is surely among the most widely sung American songs of the past half-century. It is performed by church choirs, by school choirs, by college a capella groups, by street-corner doo-wop quintets, by YouTube’s bedroom balladeers, by the United States Navy Band. It’s ecumenical, transcending genres and eras and generations and political affiliations. It has been covered by Stevie Wonder and Al Green and Clara Ward, by Jimmy Buffett and Bon Jovi, by Shawn Mendes and Nick Jonas. Jazz pianists have swung it, Imagine Dragons have mauled it. It’s been sung on “Empire” and on “Glee”; it was the theme song to a Morgan Freeman movie called, yes, “Lean on Me.” Hillary Clinton belted it out on ”Saturday Night Live,” in a duet with Kate McKinnon.

It is the kind of song that gets dragged out on heady occasions, to impart a sense of significance and solemnity. It was performed by Mary J. Blige at the Lincoln Memorial, in a concert marking President Obama’s inauguration. Sheryl Crow, Keith Urban, and, I regret to report, Kid Rock, performed it in 2010, on the “Hope for Haiti Now” earthquake relief telethon. Garth Brooks sang it, after a fashion, in a medley with “America the Beautiful,” at a 2011 Kennedy Center gala whose attendees included four former U.S. presidents.

There’s much more to Bill Withers’ catalog than his immortal hits “Ain’t No Sunshine” and “Lean on Me.” Here, a deeper dive into his short but brilliant career.

The song’s exalted status has been underscored in recent months. In the early weeks of the coronavirus lockdown, quarantining residents of New York and Dallas sang “Lean on Me” at their apartment windows to pay tribute to essential workers. The song has been inescapable during the Black Lives Matter protests, sung by demonstrators across the country, from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., to Orlando to Morgantown, W.Va., from New Jersey to Tennessee to Missouri to Illinois.

What do all of these singers hear in “Lean on Me”? They hear a message of friendship and fellow-feeling so straightforward it may at first appear banal.

Lean on me

When you’re not strong

And I’ll be your friend

I’ll help you carry on

For it won’t be long

‘Til I’m gonna need

Somebody to lean on

On the original recording, these lines, delivered by Withers in a warm, commanding baritone, land as a simple statement of fact, stripped of sentimentality. This was typical of Withers, who died in March, at age 81, of coronary heart disease. He sang in the voice of a stoic but sensitive Regular Joe; the Roots drummer Questlove has called Withers “the last African American everyman.” As a songwriter, he was a master of concision, with a genius for boiling down stories to their essence, saying it all with simple chords and a few well-chosen words. Withers’ plainspokenness and gravitas made any song feel homespun — like a folk artifact that was discovered under a rock or pulled from loamy soil.

You could say that this was his birthright. He had salt-of-the-earth bona fides to match any American troubadour’s. He was born in Slab Fork, W.Va., a tiny coal-mining hamlet. He joined the Navy at age 17 and served for nine years; he began writing and singing songs while stationed in Guam. In the late 1960s, he moved to Los Angeles, where he found work in an aircraft parts factory. Even after signing a record contract, Withers kept his job, unconvinced that a music career would pan out. The cover of his debut album, “Just as I Am” (1971), shows Withers holding a lunch pail and leaning against a factory wall. The photo session was held at his workplace, on his lunch break.

“Lean on Me,” from the 1972 album”Still Bill,” was his biggest hit. Withers told Rolling Stone that he composed it on piano, in rudimentary fashion. “I didn’t change fingers,” Withers said. “I just went one, two, three, four, up and down the piano… Even a tiny child can play that.” The lyrics are nearly all monosyllables, and in singing the verses, Withers largely shuns syncopation, letting the words fall out precisely in time with the chord changes, one syllable per chord. The effect is like a children’s song or a homily, a lesson enunciated with utmost clarity, so its meaning won’t be missed: “If there is a load / You have to bear / That you can’t carry / I’m right up the road / I’ll bear your load / If you just call on me.”

- In a 2004 interview on the website Songfacts, Withers called “Lean on Me” “a rural song that translates … across demographical lines.” The song distills the social compact: I’ll take care of you; you’ll take care of me; we’ll look out for each other. It’s a pledge of allegiance, not to a flag or country or creed, but to each other — to an ideal of unity and community, of shared burdens and common destiny.

Traditional national anthems direct our eyes upwards. The vision of these songs is celestial: O beautiful, for spacious skies; the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air. Such songs celebrate power, majesty, monumentality; often, their view is militaristic. Our current political predicament is a reminder of how thin certain lines can be, how veneration of country can curdle into nationalism, and how nationalism can tilt toward fascism. Performances of the “The Star-Spangled Banner” at political rallies and sporting events are often bombastically staged, with American flags projected on Jumbotrons and flyovers by military jets, kitsch spectacles that aim to stir patriotism through shock and awe.

“Lean on Me” could never inspire such pomp. It is a song that holds its gaze steady at the level of everyday life. It says: What’s important is the stuff happening down here. The dramatis personae are you, me, all of us. We the people.

Of course, the biggest difference between “Lean on Me” and “The Star-Spangled Banner” is obvious to all who have ears. It’s there in the tolling gospel piano chords and in the bluesy bend of Withers’ vocals. “Lean on Me” is a great piece of popular music, to be specific, a supreme piece of African American pop music — which is to say, it represents the very best of this country. Not only is Black music the finest American thing, the greatest gift that the United States has given to world culture, it is one of the deepest, most truthful repositories of American history, far more honest about the failures and possibilities of the country than the triumphalist official history, which flattens the saga into a procession of Great Men, noble principles, virtuous struggles, adversity overcome, wars won, flags whipping above battlements in the sunrise.

“Lean on Me” holds another history in its bones, from the Middle Passage up to the present day. The song is tuned into the reality that life is hard, that there is pain in the past and in the present. But it holds out hope for the future, if we have the good sense to treat each other kindly. It’s right there in the first lines of the song: “Sometimes in our lives / We all have pain / We all have sorrow / But if we are wise / We know that there’s / Always tomorrow.”

When Major League Baseball begins its coronavirus-shortened 60-game schedule next week, “The Star-Spangled Banner” will be played before the games. In the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing, we will surely see many more athletes taking a knee during the anthem. But for the moment, it seems unlikely that backlash will imperil the song itself. It is certainly farfetched to imagine Congress decommissioning “The Star-Spangled Banner,” let alone voting to replace it with the likes of “Lean on Me.” There are more pressing matters to attend to. The changes we need in this country will come not through symbolic gestures but when laws are changed, when reforms are enacted, when money is thrown at problems.

What’s more, it feels perverse to wish such a fate on “Lean on Me,” a song that is minding its own business and doing just fine as is. Some make the case that our dowdy, gauche old anthem is exactly the right fit: An official national song shouldn’t actually be a good song, and certainly shouldn’t have any trace of hipness about it. Perhaps the degree of difficulty of “The Star-Spangled Banner” is a virtue, too. A better song would inspire neither those rare revelatory interpretations — Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock, Marvin Gaye at the 1983 NBA All-Star Game, Whitney Houston at Super Bowl XXV — nor the trainwreck caterwauling of Roseanne Barr and Fergie, iconic performances in their own right.

But if the point of a national anthem is to provide a mnemonic, a reminder in music and words of the ideas and values that this place is supposed to stand for, you could do worse than “Lean on Me.” “You just call on me brother, when you need a hand / We all need somebody to lean on / I just might have a problem that you’ll understand / We all need somebody to lean on.”

When you bolster that sentiment, as Withers does, with some handclaps and a funky bassline, the words ring even truer. It’s a message you could build something on, a pretty solid foundation for a decent society. It can bear the load.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.