Coachella was supposed to start on Friday. How crazy is that?

- Share via

In any other year, Erick Martell would be slathering on the sunscreen and combing Spotify for DJs to see at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival this weekend.

For the last five Aprils, the 34-year-old Harvard Heights resident has hauled across the 10 Freeway from L.A. to Indio, staying with a big group of friends at a vacation house near the Empire Polo Club.

But as with most everything else in life right now, the novel coronavirus has demolished those plans.

“It sucks for all the people who were looking forward to it, but it was the responsible call to cancel the fest early,” Martell said.

The public should realize that COVID-19 cases are likely to rise when stay-at-home orders are eased, officials said.

Coachella’s absence isn’t the first thing on anyone’s mind right now. But just one month ago, it was front-page news when, on March 9, promoters AEG and Goldenvoice ended weeks of speculation and announced that the festival, originally scheduled for the weekends of April 10-12 and 17-19, would be postponed to Oct. 9-11 and 16-18, to be followed by the country music festival Stagecoach the next weekend. (There has been no announcement on who will be performing at the rescheduled festivals.)

Coachella’s cancellation was one of the first big signs that the virus would shatter the entertainment and hospitality industries for the year, along with almost everything else in the Before Times, pre-COVID-19. In Indio, the eerie stillness of the sculptures and white tents at the half-built festival site is a monument to Southern California life on pause.

Coachella is like nothing else in the American live music business. It’s the most profitable festival in the country, netting, as one insider familiar with its finances said recently, $75 million to $100 million annually. “Everybody we talked to — agents, promoters, managers — expected this would have been a record-setting year,” said Andy Gensler, editor of the concert-industry trade publication Pollstar.

It’s also the most culturally significant event in the annual touring calendar. Marquee acts like Beyoncé and the late Prince have used the festival to play perhaps the best shows of their lives (Beyoncé turned hers into a Netflix documentary). Breakthrough performances at Coachella have helped propel rising artists like Billie Eilish into arena stars and the festival has provided lucrative reunion settings for hallowed acts like Guns N’ Roses and OutKast.

“It’s the centerpiece to the U.S. festival season, and the fact that it’s not happening this week is very surreal,” said Mookie Singerman, a manager for indie acts Purity Ring and Caroline Polachek.

Some L.A. staging and event-production firms have, in a matter of days, remade their companies to build a first line of defense against the coronavirus.

Many acts booked for Coachella plan their record-release and touring calendars around their dates in the desert. A slot on the Coachella poster in any font size means you can market yourself as a globally important artist. Absent that, artists don’t just lose income but also momentum.

“Touring and festivals account for a huge percentage of most professional musicians’ income, like 70% to 80%,” Singerman said. “When touring is off the table indefinitely, you also lose one of the main ways to promote your album.”

He’s telling artists to focus on reaching fans online for now, because even after any stay-at-home orders subside, “it’s going to be very logistically complicated to get a weeks-long tour together.”

The Coachella Valley, whose economy relies on the festival as much as its famous sunshine and Midcentury Modern architecture, could face its most brutal tourist season yet.

There are no broad estimates yet for the total loss of all the hotels and rental homes unfilled, the restaurants gone dark and the ticket revenue vaporized (until October, at the most optimistic). Indio nets $3.5 million of its annual $81-million budget from Coachella ticket revenue alone. One recent estimate from the Greater Palm Springs Convention & Visitors Bureau pegged the fest’s economic impact at $700 million in 2016.

“Tourism is the number one industry in the Coachella Valley, supporting over 53,000 jobs,” Scott White, president and chief executive of the bureau, said in an email to The Times. “The unprecedented public health crisis we are experiencing has paralyzed our local economy with canceled leisure travel, meetings, festivals and events. The devastating impact of COVID-19 has many in our tourism community facing extreme financial hardship.”

He’s holding out hope for a fall festival season redo. “As we look forward to fall and beyond, we are optimistic that the rescheduling of the Coachella Music and Arts Festival and Stagecoach will be a significant boost to our economy and lead the recovery going into 2021.”

The music industry is staring down the previously unthinkable wholesale loss of its live-show sector for months at least. A new study from Pollstar estimates that the live business could lose $2 billion to $9 billion, depending on how long government-mandated closures and safer-at-home orders are enforced.

Meanwhile, as fans like Martell try to stay sane in home confinement, many acts scheduled to perform or help build Coachella’s fantasia of sculptures and art are warily watching the calendar, hoping that their big moments still come through.

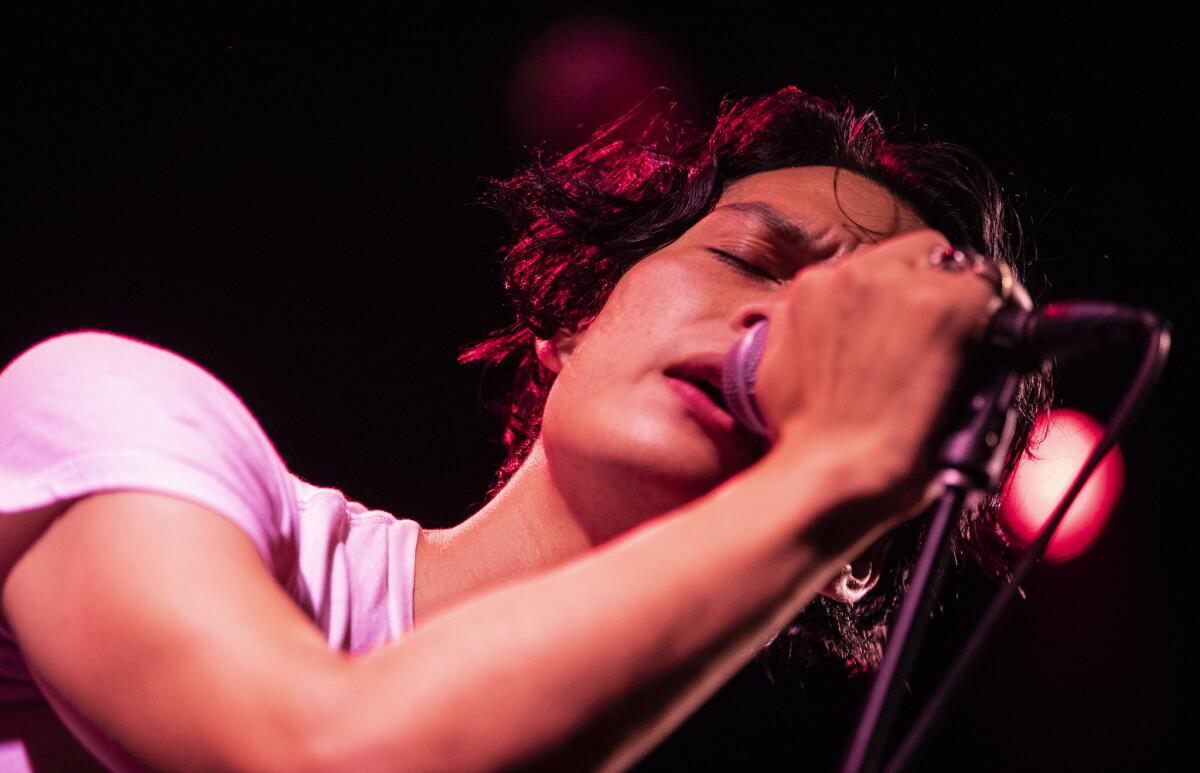

The Inglewood band Inner Wave has helped lead a renaissance of Latin indie rock influenced by oldies and the internet alike. Its debut Coachella performance, scheduled for Saturday, was supposed to be a hometown triumph for the act’s influential scene and spur some momentum for a new EP and national headline tour.

Instead, band members are stuck at home watching comfort-food comedies and enjoying other diversions like the rest of us.

“It’s hit or miss. Some days I’ll wake up and cook a healthy meal and help my parents out. But other days I wake up at 3 p.m., smoke weed and watch ‘Anchorman’ again,” said Pablo Sotelo, 25, lead singer of Inner Wave.

Band members understand the inevitability of Coachella’s postponement, though they’re a bit nervous about what the cessation of all live shows for now means for their careers. But they’re much more afraid of the irreparable damage that a recession would inflict on their already-precarious music community and neighbors around South L.A.

“Over the course of us being in this band, we’re used to stuff going south. But it’s not just happening to us, it’s been tough on everybody and especially on small business and DIY spots,” Sotelo said.

The city and state need to act much faster if they want to preserve the cultural life that makes L.A. worth the struggle, band members said.

“The first thing is they’ve got to freeze rent,” added bassist and singer Jean Pierre Narvaez, 25. “It sounds like such a nightmare to have the world ending, but you’ve still gotta send rent.”

Some Coachella artists are still making the most of it, even finding inspiration in the psychedelic boredom of quarantine.

The L.A. video-artist collective Strangeloop Studios is a Coachella veteran, creating live tour backdrops and animations for headlining acts like Kendrick Lamar, the Weeknd and DJ Snake. This year, the collective was slotted to build and run the visuals for composer Danny Elfman’s much-anticipated set and for acclaimed L.A. electronic producer Tokimonsta.

But with the collapse of the live industry, members of the collective have redoubled their efforts building a virtual artist project (akin to Hatsune Miku, the Japanese anime hologram also booked to play at Coachella this year) and a dystopian short feature film about, of all things, an apocalyptic viral pandemic that they had planned to debut between Coachella weekends.

“The grinding to a halt of live concerts accelerated our interest in spaces where you didn’t have to get together physically, but we didn’t really have a choice,” said David Wexler, Strangeloop’s cofounder and creative director. “We’ve all stepped into a sci-fi plot, but it isn’t necessarily one we want to be in.”

None of that can replace the camaraderie of hitting the field with your friends, though, and everyone in Southern California — from fans to artists to concert promoters to hoteliers to mayors — is hoping against hope that the damage done by the novel coronavirus is temporary.

“Most people’s lives will not be the same after this first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Brandon Brown, an epidemiologist at the UC Riverside School of Medicine and its Center for Healthy Communities. Brown added that it will be a slow, uncertain process determining when it’s safe to go to concerts but that big events like Coachella should be last in line to reopen. “I imagine it will be a tiered process, starting with smaller events and then much larger events like Coachella,” he said.

“Unless the number of infections is zero, there is always a risk of a second wave of infections.”

When the music does come back, amid all the new hand-washing stations and front-gate temperature checks and the fever-dream reminders of our spring and summer stuck inside, maybe festivals will feel a little more liberating again.

“People are going to be so thirsty for that,” Sotelo said. “I’m not very extroverted or social, but right now, I just wish I could see everybody, to have any reason to get together.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.