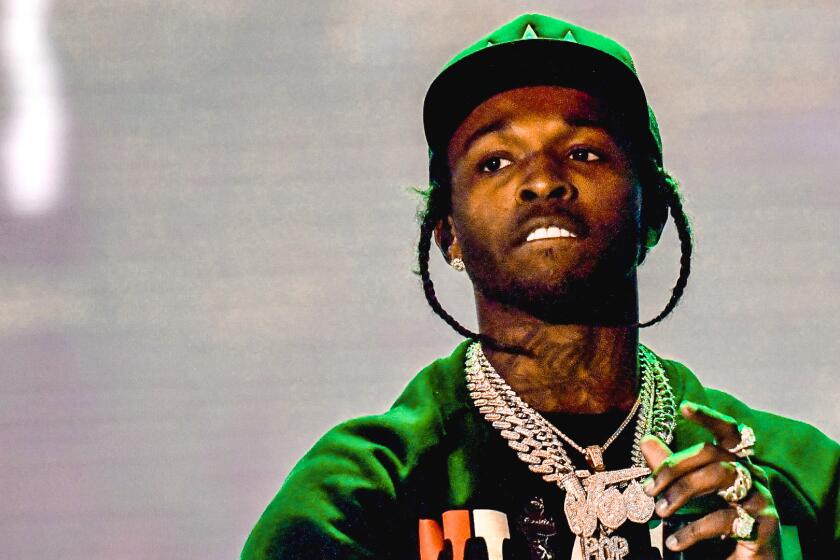

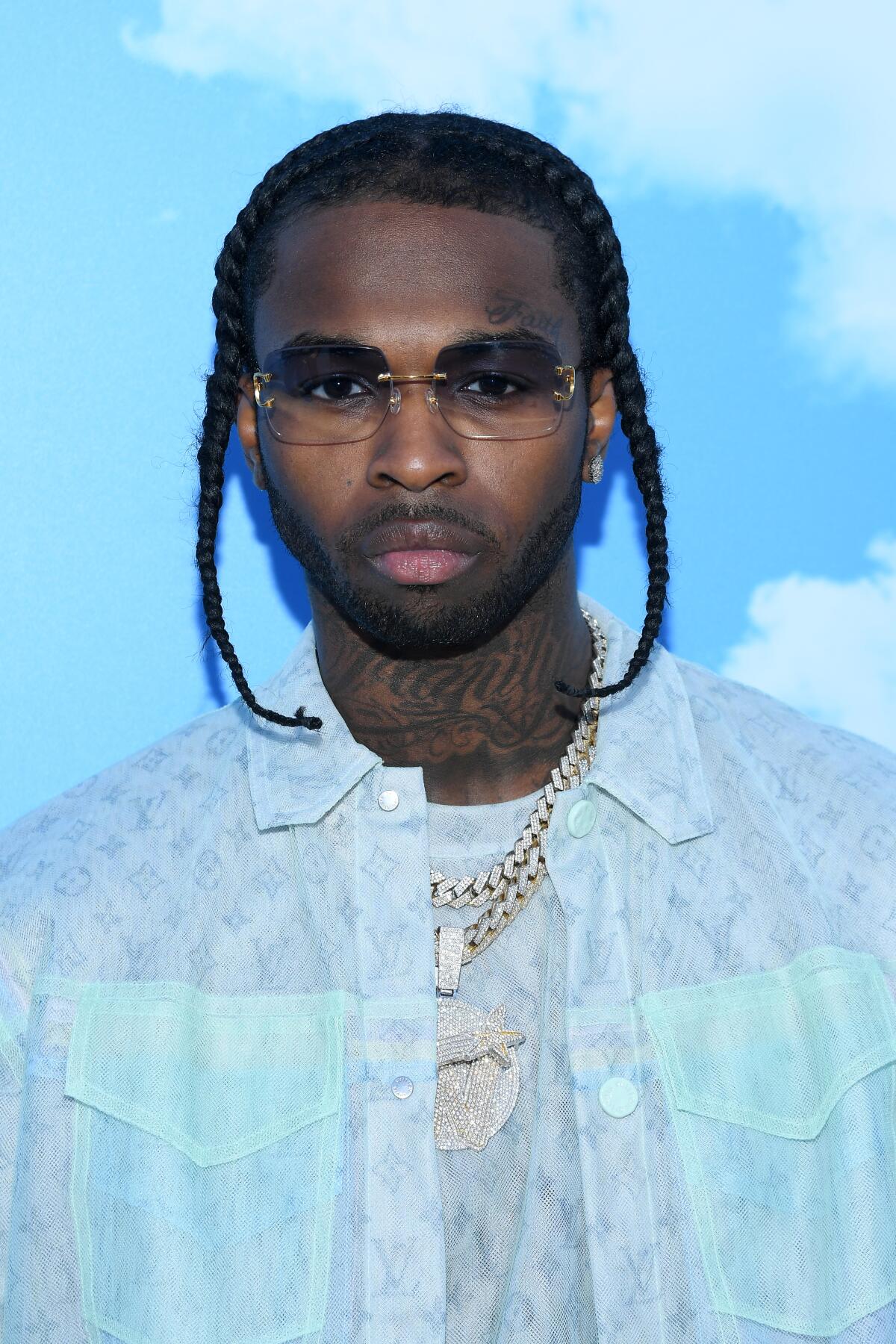

In a too-brief life, Brooklyn rapper Pop Smoke had already recast the sound, and center, of hip-hop

- Share via

It would be all too easy to simply add the killing of 20-year-old New York rapper Pop Smoke to the litany of tragedies that have plagued hip-hop recently. Nipsey Hussle at 33, Mac Miller at 26, Juice Wrld and Lil Peep at 21, XXXTentacion at 20 — it’s starting to feel like a curse.

But that wouldn’t do justice to Pop Smoke (born Bashar Barakah Jackson), who in his barely year-old career helped found a distinctly Brooklyn variant of drill music. The genre originated in Chicago nearly a decade ago, with artists like Chief Keef and his producer Young Chop, but it later refracted through NYC and London. Unlike the melodic, hazy styles that often dominate streaming today, drill music indeed sounds like a power tool: fast clips of kicks and hi-hats and gothic synthesizers, trap music played with the ferocity and precision of metal.

Pop Smoke, a rising New York rapper, was fatally shot at a home in the Hollywood Hills early Wednesday, authorities said.

Lyrically, it was anything but background music. Even when Pop Smoke was cutting loose on “the molly, the xan, the lean,” as he rapped on his breakout hit “Welcome to the Party,” bad vibes and violence were close at hand: “.380 hold a ruler, I know some n— that’ll shoot you for nothing.”

His gravelly delivery had weight and menace that locked into his tense productions, but his fleet phrasing never wavered. Megastars like Travis Scott, Quavo, Skepta and Nicki Minaj jumped on collaborations with him within weeks after his singles took off on streaming. And just as importantly, he’d already found a bravado and charisma that could have carried his city into a new wave of influence in the genre it birthed.

The details are still emerging about the motives and suspects behind his fatal shooting in a Hollywood Hills home invasion. Law enforcement officials in Los Angeles said he was a member of a Crip-affiliated street gang, and are treating his death as likely gang-related. They added that Pop Smoke may have inadvertently posted the address of the home where he was staying to social media, where his assailants may have seen it.

Born to Panamanian and Jamaican parents and raised in the Canarsie neighborhood of Brooklyn, Pop Smoke proved himself a diligent student of his city’s rap history. His delivery split the difference between the hoarse growls of DMX and the icy control of 50 Cent. It’s no wonder Nicki Minaj, another New Yorker, was perhaps his first mainstream champion. After years of dominance from Atlanta, L.A. and Miami, Pop Smoke was supposed to be Brooklyn’s new hero.

But he also found a coterie of like-minded peers like producer 808MeloBeats in London, another city where heavy sonics, thick accents and tales of urban noir ruled the rap underground. It makes sense that his second mainstream champion was the UK superstar Skepta, who must have seen an echo in the aesthetic Smoke had created.

While initial reports indicated that rapper Pop Smoke was killed in a home invasion robbery, police are still trying to sort out what happened.

“Welcome to the Party” was a song of the summer last year, despite being as un-summery as it gets: seasick grime synths and a rasping, leery hook that could start a party and imbue it with doom all at once. “Dior” was just as compelling — Pop’s guttural register took the structure of a fashion-boast track, and made it weird, scary and irresistible. He probably had the most distinct voice in contemporary rap, but never fell back on it. To use another recent reference point of New York tension, his dense sprays of lyrics had the heft of uncut gems.

He represented a new vanguard of NYC rap — cocky, appealingly edgy and seemingly arrived out of the ether, fully formed. Cops, as they do, took notice. The NYPD dealt his overnight rise a body blow when, in a letter to organizers, they strongly encouraged the promoters of October’s Rolling Loud music festival to drop him and several local peers from the festival’s New York edition, claiming they were associated with a spate of violence around the city. Some fans interpreted the police pressure as law enforcement denying a platform to one of the city’s most promising voices.

Pop Smoke had once attended a Philadelphia prep school on scholarship, but brushes with the law continued into his rap career. He was recently released from a diversion program around a weapons charge, later dismissed. Just a month ago, he was arrested in connection to the theft of a Rolls-Royce in L.A. Prosecutors in New York alleged he’d borrowed it for a music video but shipped it on a truck to his mother’s house, and he pleaded not guilty to one count of interstate transportation of a stolen vehicle.

He appeared to be rounding a bend in commercial success, however. His new album for Republic Records, “Meet the Woo 2,” debuted at No. 7 on the Billboard Top 200 album charts just last week, with a major international tour imminent.

His death has nothing to do with the drug overdoses that killed fellow hip-hop stars Lil Peep and Mac Miller and Juice Wrld. But it does add to a sense that the establishment in hip-hop, which now dwarfs rock as popular music’s most commercially and culturally dominant genre, is struggling to look after these near-teenagers who suddenly find themselves surrounded by outsized money and fame. Rappers have struggled with those challenges since the genre’s inception, but the new social-media- and streaming-fueled speed of ascent, with seven-figure paychecks following a homemade first single or two, only magnify them.

Pop Smoke gave a generation of New York rap fans a new wind at their back and did so in just a few months. That’s worth remembering.

He’s also added to the sad ledger of hip-hop artists who have been prematurely lost to drugs or violence. That’s worth remembering, too.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.