- Share via

Filmmaker Michael Mann is known for his exacting research and exhaustive preparation, work that goes into such moody, existential portraits as “Heat,” “The Insider,” “Ali,” “Miami Vice,” “Blackhat” and the recent “Ferrari.”

Mann is now giving audiences an unprecedented glimpse into his artistic process via the website michaelmannarchives.com. Launching today at noon Pacific time, the website kicks off with a deep dive into the making of “Ferrari,” including 20 video pieces specifically created for the site, previously unseen photographs, annotated script pages and production paperwork including Mann’s working notes, many in his own handwriting.

Access to the “Ferrari” site will cost $65. Following the initial launch, there are plans to eventually continue working through Mann’s filmography, with future pages focused on other films. (Users will need to purchase access to each film’s archive individually.) Fervent online fandom for titles such as “Heat” or “Miami Vice” presumably would generate great interest for this kind of behind-the-scenes exploration.

On a recent afternoon at his longtime offices in West Los Angeles, Mann met with The Times, sitting with the youngest of his four daughters, Becca Mann, who worked closely with her father in organizing the archives.

The director and stars Adam Driver and Penélope Cruz discuss the making of the Italian-shot biopic that revs this year’s Oscar season into the red.

Mann’s notoriously hard-charging demeanor seems softened by the presence of his daughter; he appears energized by their work together. In conversation, Mann recalls — with startling detail — decades-old pieces of research or specific moments from the production of his older films.

The existence of Mann’s extensive personal archive was the initial impulse behind the online project, the simple fact that all this material was there for the posting. From there, though, it began to take on a larger purpose.

“It is a spectacular, rewarding, creative act to direct a motion picture,” says Mann, 81. “It’s a very large endeavor. The movie is two hours — making it is a year and a half. So much goes into deciding, thinking through what you are going to do.”

Continuing, Mann speaks to something deeper. “Directors have no idea how any other director makes a movie,” he says. “And so we each evolve our own particular process. This is an opportunity to pass that on, convey something I’m just very enthusiastic about. I think it is the best work that any man or woman can do, period. And I’ve thought that since I was 20 years old. And my enthusiasm for it is absolutely unwavering and unremitting.”

Clip from a behind-the-scenes website by the filmmaker Michael Mann. (Michael Mann Archives)

“Ferrari,” set in Italy in 1957, tells the story of a turbulent period in the life of Enzo Ferrari, the Italian automaker who created the famed brand. Played by Adam Driver, Ferrari is seen scrambling to keep his business afloat and put together a winning auto racing team all while juggling a personal life that finds him caught between his estranged wife, Laura (Penélope Cruz), still grieving the untimely death of their son Dino, and another woman, Lina Lardi (Shailene Woodley), with whom he secretly has a young son, Piero.

The new website is structured around six scenes in “Ferrari,” including two that Mann describes as the “most pivotal” in the movie, a sequence in which the characters attend an opera performance and a volcanic argument between Enzo and Laura Ferrari at home.

Other sections of the site deal with the re-creation of the Mille Miglia auto race and the horrific, fatal 1957 crash at Guidizzolo, exploring everything from the re-creation of vintage racing cars to the special camera rigs used to capture the stunts.

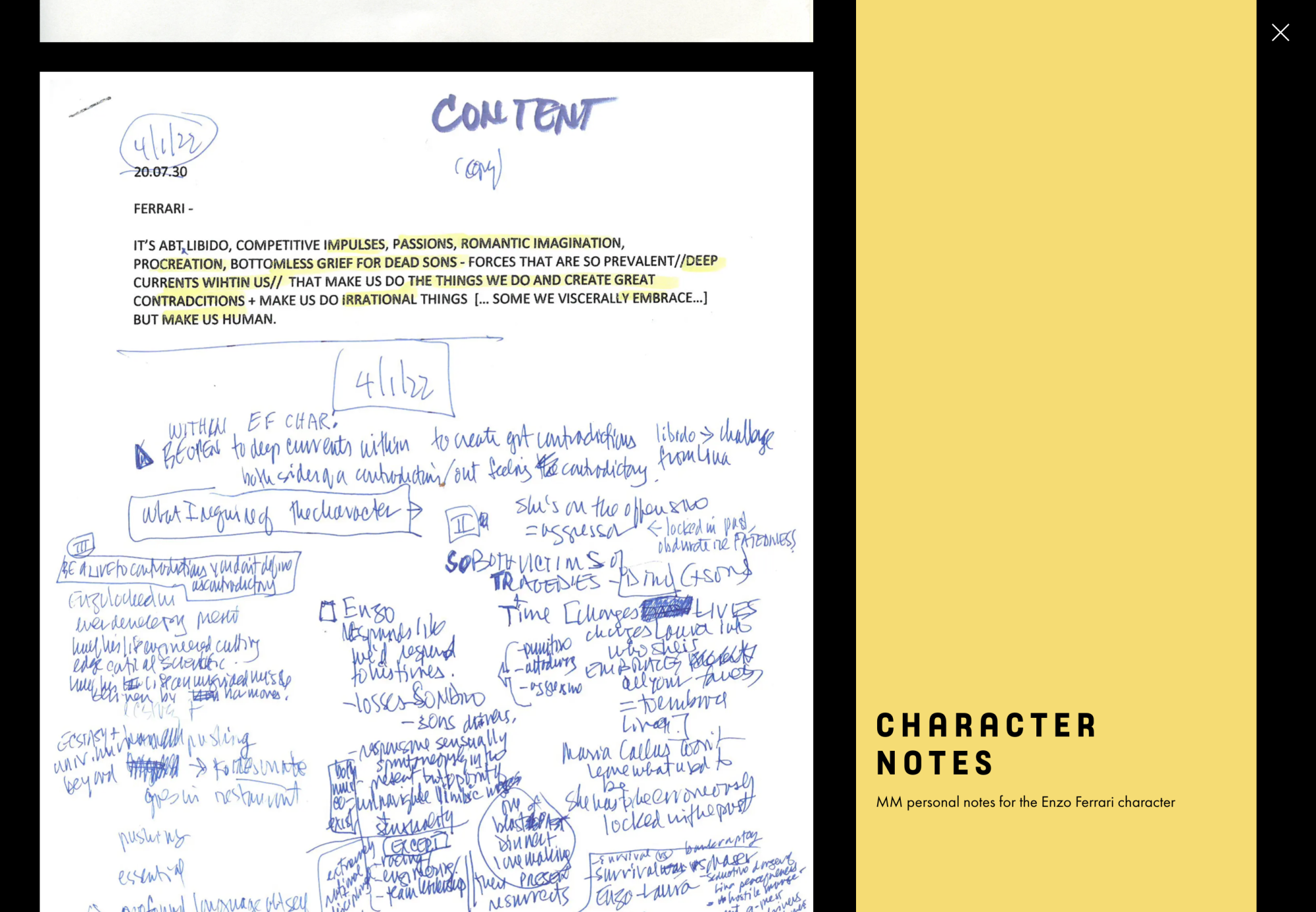

Some of the most remarkable documents on the site are Mann’s personal handwritten notes, in which he can be seen working through layer upon layer of meaning and intention. “The most critical person for me to direct is myself,” he says.

Those free-flowing comments are then filtered into more formal documents for distribution to other people in the production, as ideas are refined and honed. The continuity of the process is all the more noteworthy in that the date from one page to the next can sometimes jump a number of years. (Mann’s interest in “Ferrari” dates back to the 1990s.)

The site’s video pieces are more extensive and in-depth than those that typically accompany a movie’s promotion. They may toggle between rehearsal footage of Driver and Woodley and the final filmed version of the same scene. Audio sources come from Mann’s rough preproduction recordings, such as when he and Cruz discuss Laura and Enzo’s relationship long before the film’s shoot. (Mann’s preproduction photographs of Cruz in the Ferrari family’s actual apartment may be among the most striking imagery on the entire site.)

Mann‘s archival material has, up to now, been stored in multiple locations, divided among paperwork, film elements and physical objects. Becca Mann began working as an archivist for her father around 10 years ago, at first just to check that the materials were being stored properly, and then saw her involvement grow over time.

“This is what happens if you hang around with him,” Becca Mann, 43, says with an affectionate smile. “I go visit storage to see if it’s dusty and then —”

“In 25 words or less, it turned into this,” adds her father with a laugh.

Becca Mann recalls making discoveries of items that she was personally fascinated by, and knew that other people would appreciate the opportunity to see them too.

“We’d run across some kind of crazy, beautiful document that’s covered in coffee stains and it’s got the whole crux of ‘Heat’ on one page,” she says. “That’s where wheels started turning about how to share it — what’s the best and most appropriate and also most direct thing to do with the stuff.”

Becca Mann notes that, as one goes further back in time, there tends to be less material on each film, which may be challenging for further iterations of the archive website. Mann himself frequently uses his archive for research on projects. For “Ferrari,” Mann’s working process was the same as it has been on previous movies, with the exception that there was even more attention paid to documenting the work along the way.

In explaining his interest in the archives project, he reflected on how other filmmakers have inspired his evolving practice over the years. He cites the deep and ongoing influence of Russian director Sergei Eisenstein, as well as what he learned about storytelling from his friend, filmmaker Sydney Pollack, who collaborated on early versions of the “Ferrari” project.

While working as an assistant to George Cukor in London in the late 1960s on a film that was never made, Mann saw the director of “The Philadelphia Story,” “A Star Is Born” and “My Fair Lady” give an adjustment to an actor during a rehearsal.

“I don’t know what he said, but it lasted about 10 or 15 seconds and he walked away and the performance went from A to Z,” Mann said. “And that instilled in me that if you want to direct, you have to be able to do that. You have to know what to say to get inside a very determined, hardworking actor.”

“Ferrari” was seen as a box office failure, making just over $42 million worldwide on a reported budget of $95 million and earning no major awards recognition. Yet that hasn’t diminished Mann’s feelings toward the decades of work that went into creating it.

“I’m confident in the film’s long-term relevance,” Mann says. “I believe it’s a good film. I think Adam’s work is great. Penélope’s work is great. Shailene. The writing by Troy [Kennedy Martin] is quite terrific. No doubt about that.”

Many of Mann’s films have had a long tail, finding passionate and supportive audiences over time. Just look at recent screenings of “Miami Vice” in New York and Los Angeles or the enthusiasm around a recent 4K disc release of “Blackhat.”

“That’s not a mystery to me,” Mann says of why some of his films take longer to catch on with audiences than others, citing the complex “contrapuntal” ending of “Heat.”

“It’s emotionally conclusive, but it doesn’t leave you with: OK, that’s over, where are we gonna get a pizza?’ It’s not fast food. There are a lot of layers to these things.”

Which Mann classic will the archive explore next? “We don’t know what we want to do next,” Becca Mann says. “We’ll learn a lot about what people respond to. This project has an enormous amount of material in it. The objective is to do something activating and alive with the archive.”

Meanwhile, Mann notes he is deep into writing the screenplay adaptation of his novel “Heat 2,” with a desire to begin shooting at the end of this year or beginning of 2025. On those casting rumors involving the likes of Driver and Austin Butler to step into roles originally played by Robert De Niro and Val Kilmer, Mann says simply, “I can’t talk about that.”

The Michael Mann Archives project provides unique insights into the distinctive working methods of a director who has been at the forefront of Hollywood for more than four decades. Allowing audiences under the hood, as it were, only deepens one’s appreciation for the intensity of work that goes into making one of his films.

“I wouldn’t want to make a movie any other way,” Mann said. “If somebody said, ‘Here’s $20 million, show up three weeks before we start shooting,’ that would not be for me. ‘Make it up as you go’ is not for me.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.