My journey to the heart of Andrew Haigh, the director behind the year’s best film

- Share via

You might say I knew Andrew Haigh before I knew myself.

Strange, perhaps, since I haven’t met him until now, ensconced in the corner of a banquette at a Beverly Hills hotel restaurant. But through Russell (Tom Cullen), the uncertain protagonist of Haigh’s breakthrough 2011 feature, “Weekend,” and Patrick (Jonathan Groff), the hapless striver at the center of his HBO series “Looking,” I not only developed my voice as a proponent, and occasionally a critic, of LGBTQ images in popular culture, I also came to understand that representation — or, more precisely, self-identification — is most potent when the mirror shows you your flaws.

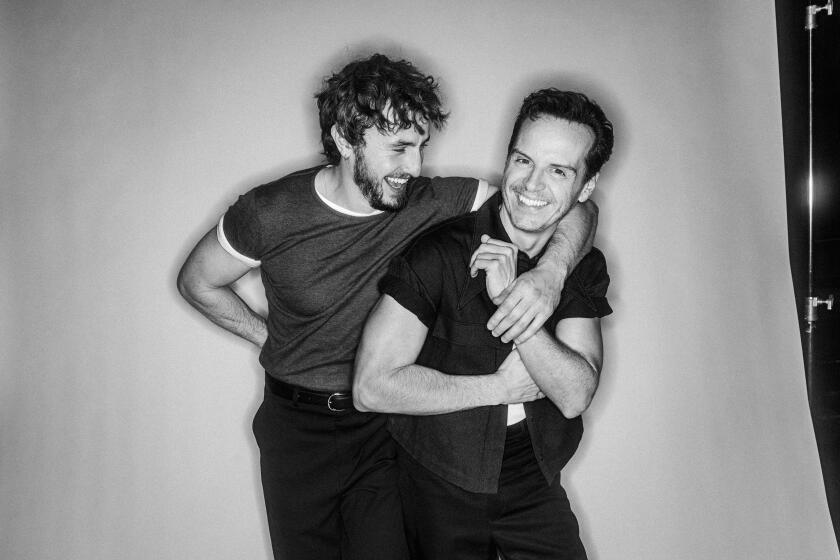

With “All of Us Strangers,” the most nakedly emotional film in Haigh’s oeuvre and his first explicitly queer project since 2016, he’s made that mirror a guiding principle. Adapting Taichi Yamada’s 1987 novel “Strangers” to his own sensibilities, the writer-director turns his focus on a lonely, middle-aged screenwriter named Adam (“Fleabag’s” Andrew Scott), who returns to his childhood home in search of inspiration for a new, deeply personal script. In the process, he steps through the looking glass, reconnecting with his parents (Claire Foy and Jamie Bell), who died in a car accident when he was about 12, and sparking an intense affair with Harry (Paul Mescal), seemingly the only other tenant in his high-rise apartment building.

Even if one hasn’t experienced Adam’s particular brand of grief, though, the film — part family melodrama, part intergenerational gay romance, part ghost story — remains acutely heartbreaking. For many gay men of Haigh’s generation (and my own), “All of Us Strangers” expresses the inexpressible: all we didn’t say and still haven’t, and maybe can’t and probably won’t.

“It’s something I’ve wanted to tell a story about for quite a long time,” Haigh says of the film, in theaters Friday. “How different and how complicated it is within a family when you’re gay.”

Though he spent his early childhood near Croydon, south of London (in the same home where he filmed the family scenes in “All of Us Strangers”), Haigh, 50, was born in his parents’ native northern England. His mother, an Irish Catholic, was a stay-at-home mom and secretary, among other jobs; his father worked in sales for the U.K. soft drinks company Britvic.

It was not, Haigh says, a “culturally engaged” household. “When you grow up in that environment, you don’t have access to the films that I now love,” he recalls. Instead, like many budding LGBTQ cinephiles in the suburbs before the advent of streaming, he clung to a handful of readily available titles that could pass for mainstream while sustaining a queer subtext. “I would literally watch ‘9 to 5’ almost every day in the summer holidays,” he says with a laugh.

The best movies of 2023 include ‘Oppenheimer,’ ‘Past Lives’ and ‘Poor Things,’ according to our critic Justin Chang.

Around the age of 15, Haigh, propelled by word of its notoriously lifelike sex scene between Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland, rented Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 horror classic “Don’t Look Now” and began a fascination with onscreen intimacy that would come to define his work. Since his first feature, “Greek Pete,” a sexually frank 2009 docudrama about a London rentboy, Haigh’s unabashedly erotic interest in our flirtation, our foreplay, our bare, bouncing asses and semen-slicked chests, has distinguished him as a perceptive chronicler of gay sexual mores — in part because he has always treated the subject without the hand-wringing that often accompanies it.

“There has been so much shame put around the idea of sex, especially for a queer person, and I think what I’m trying to do is take that shame out of it,” he says of his approach, which creates images — a nose exploring a leather boot, frosted white wetness pooling in a navel — that would be inconceivable from a straight filmmaker. Yet Haigh, who “can’t imagine movies without sex scenes,” remains sympathetic to viewers critical of them.

“Audiences have been burnt by seeing sex scenes in cinema and on TV that are just there for titillation and nothing else,” he says. “There’s not necessarily a place for that — although, you know what? Even that can be fun sometimes too.”

“Don’t Look Now” led Haigh to other Roeg landmarks, such as “Walkabout” and “The Man Who Fell to Earth,” and to an interest in classic and art-house cinema. The passion came into full flower when Haigh, after graduating from Newcastle University with a degree in history in 1995, went to work as an usher at the National Film Theatre in London. “You could watch three films a day sitting in the back of the theater,” he says. “You could watch ‘L’Avventura’ in the morning, and then you’re watching Cassavetes, and then you’re watching something else. It blew my mind.” This informal education continued even as he began to accrue credits as an assistant editor, including a stint in Prague on the 2003 Jackie Chan film “Shanghai Knights” that he remembers mostly for off-hours spent studying the films of Ingmar Bergman.

Haigh, who grew up at the height of the AIDS crisis in Margaret Thatcher’s England, was nearing the end of the “long, long” process of coming to terms with his sexuality. The conversations Adam has with the specters of his parents in “All of Us Strangers” bear the unmistakable imprint of that experience. In one scene, after coming out to his mother, Adam finds himself assuaging her litany of fears about his health, his happiness, his prospects in life; in another, he recalls the indelible mark his father made by telling him “not to cross my legs like a woman.” The film is not autobiographical, exactly — every gay man I know has such stories in his arsenal — but it is profoundly personal.

Haigh, who is now married to the writer Andy Morwood, with whom he shares two children, came out in his mid-20s, and says his parents have always been supportive. Still, he notes, when he calls up memories of the phrase “Andrew’s a pouf” from desktop scrawls and overheard conversations at school, the aftereffects of those painful adolescent experiences linger on into adulthood. “There’s something at work within us which makes us feel separate,” he says. “I’m accepted by my family, but why do I still feel like I’m hovering around the edges of things?”

“All of Us Strangers” is not only an exploration of this distance but also an emblem of it. Haigh hasn’t had the candid conversations with his parents that Adam does on screen, at least not in a direct sense, though the film has sparked some “questions,” and “worries,” from his mother. (His father, who suffers from dementia, has not seen the film.) Instead, Haigh describes the process as a way of having the conversation with himself: “You can come to terms with things internally without necessarily having to do it in your real life,” he says.

The metaphysical chamber drama, starring Andrew Scott, Paul Mescal, Claire Foy and Jamie Bell, is an emotionally overpowering new work from director Andrew Haigh.

The vulnerability that Haigh taps into when telling queer stories is not without risks, especially when the terrain is as well-trod as the coming-out narrative. Among the largely favorable notices for “All of Us Strangers,” the criticisms of the family story line — “disappointingly simple,” “broad and familiar,” marked by “sentimentality and commonplaces” — register most pointedly, perhaps because they are so reminiscent of Haigh’s last foray into the realm of LGBTQ representation. When “Looking” first premiered in 2014, it was pilloried by prominent queer commentators as “boring” and a “mediocrity,” failing to attract enough viewers, straight or gay, to remain on the air for long. It was canceled, after just two seasons, in 2015, and except for a TV movie coda, Haigh has — consciously, he says — not taken on a queer-themed project since.

“When you put something out into the world and then you’re criticized by the community you’re supposed to be a part of, it can be quite bruising,” he explains, likening each negative social media post to “a stab to my heart.” “For a while I felt like, ‘I just don’t know if I want to get back into that arena again.’”

“Looking” at times earned the criticism that it did not capture the diversity and vibrancy of San Francisco’s queer community, and in fact addressed those claims head-on in its sublime second season. But it’s still hard not to see certain complaints about the series — precisely constructed and emotionally astute — or the boldly imagined “All of Us Strangers” as a failure to recognize what makes Haigh tick. He is a filmmaker forever poised on the edge of being misunderstood.

“I feel like I float somewhere in the middle of conventional and subversive, or commercial and art house,” he says of his position, having made peace with it. “And to me, philosophically, that makes sense. I float between desperately wanting stability and wanting glorious freedom. From being at the bosom of my family to being a lone wolf.”

At the heart of my kinship with Haigh is this belief that the “conventional” desire, the “commonplace” hurt, is no less worthy of close examination. After all, what I share with his characters, with his Adams and Harrys, his Russells and Patricks and Petes, is distinctly unremarkable: the same secrets, the same fears, the same joys. The same parents from whom I shield my innermost thoughts, the same lovers to whom I spill them. The same home movies of Christmas morning, the same longing glances across the bar, the same nostalgia, the same heartache. The same pull, at times so strong it feels gravitational, to slip my line from its mooring and drift silently away. The same things I didn’t say and still haven’t, and maybe can’t and probably won’t.

“It’d have devastated me to see somebody else play it. I don’t think I could watch it,” Paul Mescal says, contemplating his reaction if he hadn’t landed a role in the Andrew Haigh film..

Haigh’s work does for me what the filmmaker says a torch song or a tearjerker does for him: “That is the thing that makes me feel less alone,” he says. “Not more alone, less alone. Life is very difficult in big and small ways for absolutely everybody.”

“All of Us Strangers,” down to the seemingly innocuous phrase Haigh appends to the original novel’s title, is ultimately a statement of his conviction that there is something “beautiful and sweet and tender” in our sorrow and disappointment — that grief, for instance, might be understood as photonegative proof of the existence of love. By his own admission, he is a “melancholy” filmmaker, but in the end his drama is built not from loneliness or isolation so much as unbearably intense connection, inevitably severed by circumstance or space or time.

“We go through life hopefully loving people along the way and then, often, losing them,” he says. “Even if you don’t lose them through death. Relationships end, you move on, you meet someone else, that may end. Life is a succession of losses, but love is the thing that remains.”

In this sense, perhaps every Haigh story is a ghost story, and every protagonist a subtle reminder: All of us mean enough to be someone else’s ghost.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.