- Share via

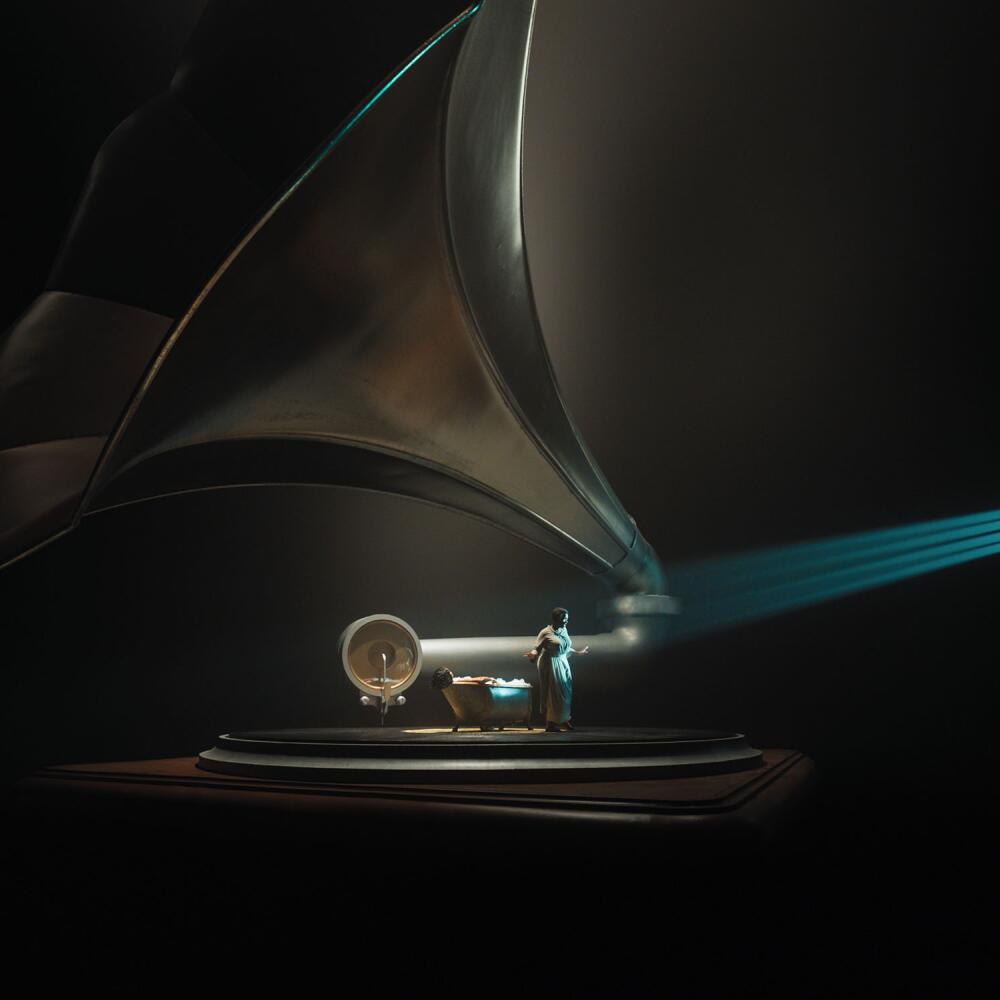

There’s a dazzling moment in the new “The Color Purple” (in theaters Dec. 25) in which Fantasia Barrino sings while walking atop an enormous shellac record spinning on a huge gramophone, all while rotating around Taraji P. Henson soaking in a bathtub.

Maybe that seems incongruent with Alice Walker’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, which recounts the abuse and ascendancy of Celie, a poor Black woman living in the rural South in the early 1900s. But this visual — a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it image in the trailer for the Warner Bros. release — is emblematic of a relatively psychologically unencumbered approach to the revered story that, though already adapted into an Oscar-nominated film and a crowd-pleasing Broadway musical, had yet to reveal its depths.

“I didn’t see why it needed to be remade — that was just my honest opinion at first,” admits musician-turned-director Blitz Bazawule. But in revisiting Walker’s deeply moving book (most of which is written as Celie’s letters to God), Bazawule found a different way into the roots of the character’s self-realization.

‘Tis the season for much more than gift exchanges, cocktail parties and cozy sweaters: The holidays bring with them a bumper crop of films and TV shows, and The Times is here as your guide. Through Sunday, we’re covering the key titles to watch this season, from late-breaking Oscar contenders and acclaimed TV dramas to holiday classics old and new. Hot cocoa sold separately.

“Celie had a real imagination, and perhaps that’s how she was able to deal with all the hurt she was going through,” he says of the story’s soft-spoken heroine. “I felt that if I could really lean into that — and be proximate to her joy, her pain, her isolation — it would be a strong and worthwhile contribution to not only the canon of ‘The Color Purple’ but also the medium of musicals.”

Bazawule presented previsuals of his “giant gramophone” scene — a snippet of his storyboarding of the entire movie, complete with sound effects and voice-overs from the script — to whoever was on the fence about yet another adaptation.

“Anyone who saw it immediately knew that, no, we are not making ‘The Color Purple’ that you think you know,” he says. Exploring interiority by way of magical realism was a storytelling strategy that Bazawule had already harnessed in his 2018 Ghanaian-set feature “The Burial of Kojo,” which he wrote, directed and scored.

The pitch convinced Barrino, who was hesitant about returning to Celie after playing the emotionally onerous role on Broadway. “She saw that my intent was to do something radically different and take some real chances,” recalls Bazawule.

The idea to revisit Celie’s journey onscreen — this time, as a musical — was prompted by the runaway success of the 2015 Broadway revival, which reconceived Walker’s narrative “as a communal meditation on a modern American myth,” wrote Times theater critic Charles McNulty at the time. With minimalist sets and powerful performances by Cynthia Erivo and Danielle Brooks, the stripped-down production won two Tony awards; its cast recording won a Grammy.

“Alice Walker has essentially written a Black Shakespearean story, and Shakespeare has been interpreted a thousand different ways over the years,” says Scott Sanders, a producer on the new film as well as the stage musical. “It was clear that ‘The Color Purple’ was relevant, important, and had joined the canon of great musical theater.”

After wrapping the Broadway run, Sanders began talks with key players on the 1985 film: director Steven Spielberg, who still held the title’s film rights, and star Oprah Winfrey and producer Quincy Jones, both of whom also produced the Broadway musical. (Spielberg’s movie, though lauded for bringing Walker’s story to a wider audience, was criticized for its lack of nuance and for promoting stereotypes about Black men.)

“We wanted to be honest about how Celie suffered, but at the same time, we didn’t want the film to feel like a slog,” says playwright and poet Marcus Gardley, who adapted the script. The new movie sporadically escapes into joy with its musical numbers, which allow the viewer to track Celie’s emotional journey without being overwhelmed by her horrific traumas, including being raped by her father, abused by her husband and separated from her sister and children.

“Anytime we felt like the film was plunging too long into tragedy, we wanted to do something organic to lift the audience up,” adds Gardley. “And how did these people get through it? They used humor, laughter, music, imagination and the beauty of the land. Everything we were pulling up to bring levity to this story was already there in Celie’s world.”

There was also latitude in the character of Celie herself. “She doesn’t talk that much to people at first,” says choreographer Fatima Robinson, “but quiet people observe everything. They take in so much when people think they aren’t even paying attention. That gave us the creative license to go anywhere.”

The film’s most ornate dream sequence — even more so than the giant gramophone — sees Henson’s enigmatic jazz singer Shug Avery taking Celie on a date to the movies. Suddenly, “The Color Purple” transports us to a sumptuous Art Deco concert stage, complete with an all-Black orchestra that plays “What About Love?,” the tender duet in which Shug and Celie contemplate their budding romance.

Each of these fantastical leaps into Celie’s mind never feels too far from her reality, and that’s by design.

“[Cinematographer] Dan Laustsen and I were very adamant about not doing what a lot of musicals do,” recalls Bazawule, “which is creating these incredibly inventive camera movements for the big musical scenes, and then when it comes to the more ‘mundane’ narrative scenes, it just becomes quite basic, and it ends up looking like two different movies. We agreed early that, whether photographing large-scale choreography or intimate scenes, we were going to invest in long takes, and let the camera move as a living, breathing organism.”

Other musical moments are more subtle. For instance, the movie opens with an aerial shot of “Mister” (Colman Domingo) plucking a banjo. The horse he rides is accompanying him like a percussionist, hoof by hoof. “We rehearsed the hell out of that and, as you can imagine, that horse is not easy to keep on beat,” says Bazawule with a laugh.

“Especially when the circumstances are ugly, your worlds have to be beautiful,” says the director, who spent months scouting (“driving the length and breadth of Georgia,” he remembers) to find striking locations. Those include a waterfall for the ethereal “She Be Mine” number (cut from the original musical but here restored), plus sprawling Spanish-moss-draped oak trees and a swamp that the production could drain to build Harpo’s juke joint and then refill for Shug Avery’s grand entrance. And because Spielberg shared regrets that the antebellum-style house in his film “misrepresented” Mister, Bazawule opted for a more humble home, built by architect Horace King.

The ambitious shoot was delayed a year by the pandemic, which turned out to be a blessing. Coming off Beyoncé’s visual album “Black Is King,” Bazawule was grateful for the extra-long preproduction period to fine-tune every element.

“The beautiful thing about working with Beyoncé is the detail-orientedness she brings,” he says. “She’s Beyoncé because she has her eye on every tiny detail. Coming into a film this expansive and with this many brilliant artisans, I definitely learned from her to be informed about what everyone is bringing to the sandbox we’re playing in, and to understand how it functions as part of the storytelling.”

Says screenwriter Gardley, “My mother teasingly says to me, ‘If you mess up this movie, don’t come home.’” He found comfort in a piece of wisdom from novelist Walker decades ago, one he’s happy to relate: “If you get hired to be involved in any shape or form of ‘The Color Purple,’ my ancestors have chosen you. And you can do no wrong, because they’re very picky.’”

Though the movie-musical is set for a theatrical release on Christmas Day, Bazawule won’t have to wait for the reaction that matters most to him.

“Alice Walker visited us on the set and asked to see what we had been shooting,” he recalls. After showing her a take, “I heard this loud sobbing and felt hands hugging me from behind,” he says. “She laid her head on me and kept saying the same thing over again: ‘This is what I always hoped it would be.’”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.