An AI nukes Hollywood in ‘The Creator.’ The movie’s director has thoughts about that

- Share via

It’s tricky enough in today’s IP-obsessed Hollywood to market an ambitious original science-fiction film. Throw in a historic strike and it becomes a whole lot harder.

For Gareth Edwards, who directed 2014’s “Godzilla” and 2016’s “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story,” selling his new sci-fi epic “The Creator” has been a lonely venture. His cast members, including John David Washington, Gemma Chan, Allison Janney and Ken Watanabe are unable to promote the film due to the ongoing actors’ strike.

“I’m like a groom in an empty church at my own wedding,” Edwards joked over Zoom from a hotel room in Madrid on a recent morning. “It’s a very surreal experience.”

What makes it even more surreal for Edwards and Walt Disney Co., which is releasing the film wide on Friday, is that “The Creator” centers on artificial intelligence, which also has been among the central issues in the Hollywood strikes. (Two days after this interview was conducted, the Writers Guild of America came to a tentative agreement with the studios and streamers; SAG-AFTRA remains on strike.)

Running counter to the anxieties of the moment, AI is portrayed in “The Creator” as a force for good — or at least not as a cold and merciless techno-evil, a la HAL in “2001: A Space Odyssey” or Skynet in “The Terminator.”

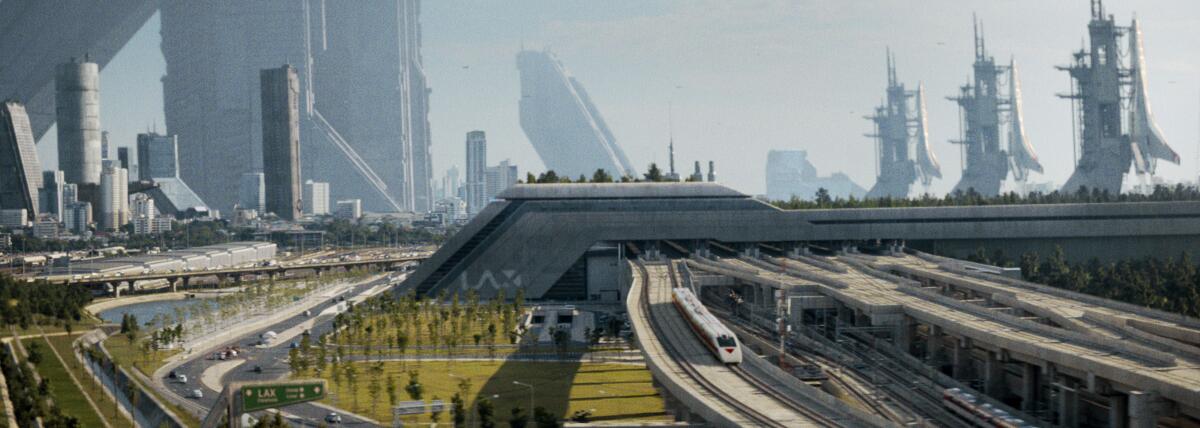

Set 40 years from now, “The Creator” posits a future in which America goes to war against artificial intelligence after (irony alert) an AI-sparked nuclear strike on Los Angeles kills nearly a million people. Washington plays Joshua, an ex-special forces agent recruited to locate a powerful weapon being developed in New Asia, where humans are still living in relative harmony alongside robots and human-like “simulants.” When he discovers that the weapon is actually a simulant child (Madeleine Yuna Voyles), Joshua finds himself torn between his mission and his desire to protect the lovable and all-too-human sentient being he nicknames Alphie.

It remains to be seen how audiences will respond to “The Creator,” which has received mixed reviews (including ours). But within the film industry, now grappling with the implications of rapid advances in AI, the film has taken on a timeliness that Edwards, who co-wrote the screenplay with Chris Weitz, never anticipated.

The Times spoke with Edwards about the inspiration behind “The Creator,” how he’s navigating this delicate moment in Hollywood‘s history and his hopes to stay on the good side of our coming robot overlords.

I’m sure after “Rogue One” you got all kinds of appealing offers. How did you end up doing an original sci-fi project about AI?

I never had an agenda about robots and AI or anything like that. The crude way to explain it is, to me, there’s a holy trinity of science fiction: You have a choice to either do aliens, spaceships or robots. I’d done aliens and spaceships, so it was, OK, I guess maybe I can try and do a robot movie next. Essentially I was trying to look for something that was achievable but not so crazy ambitious that it will cost you $300 million.

I was very much inspired by James Cameron, which I think is clear when you see the film. What Cameron did in “Aliens” and “Avatar” is take the Vietnam War and put it into space. I thought it’d be really interesting to take science fiction and bring it down to earth in Vietnam. The second I started picturing that kind of warfare but with robots, it felt fresh. I got so excited about that imagery that I was like, if some other filmmaker does this before me, I’m going to be so jealous.

For a long time, artificial intelligence was considered the stuff of sci-fi and esoteric academic study, then suddenly we all woke up in the last year and there was ChatGPT and MidJourney and these other mind-boggling AI tools. What was that like to experience while actually making a movie about AI?

I started writing in 2018 and AI was like a distant dream, like flying cars or living on the moon. I was using AI as a fairy-tale device, as a metaphor for people who are different to us — for the “other.”

Then one morning I was driving to set and looked at my phone and someone had sent me this AI story about a Google employee who had leaked a conversation with AI. I ended up reading that entire transcript of the dialogue and, like everyone, I was completely blown away and couldn’t comprehend how this was a computer. It really felt like a conscious being. I realized, I’ve been an idiot trying to set the film in 2070 — I should have picked 2024 or something. I don’t know if I’m lucky or unlucky. Hopefully the robot apocalypse will be delayed until after our film comes out.

There’s a lot of panic about AI now, that it could displace humans from jobs, if not kill us all outright. How did you arrive at what is ultimately a fairly positive and sympathetic depiction of AI?

The obvious starting point of this film was that AI was the bad guy. But whether it’s science fiction or a contemporary war movie, everyone always wants to see things from their own perspective. And the second you look at things from AI’s perspective, it flips very easily. From AI’s point of view, we are attempting to enslave it and use it as our servant and definitely not treating it as an equal with any rights at all. So we’re clearly the baddie in that situation. It was impossible to see it from that perspective and not go down that path. Obviously, if I was writing the film today, it’d be quite a different situation.

How so? Are you more frightened of AI now than you were when you were writing the film?

I’m not personally. I’ve always been quite optimistic about the future. If you look at every technological breakthrough in the last 200 years — electricity, the invention of computers, the internet — each one had this massive fear around it that it was going to destroy everyone’s jobs and make the world a worse place. And once the dust settles, I think everyone would agree they wouldn’t want to go backward.

I think AI is going to be like that too. Clearly you’re going to have a seismic disruption. Everyone is going to feel this change. But no one really knows where it’s going. I visited the top AI people at certain tech companies and you try to pull their predictions out of them. They’re all reasonably optimistic and feel safe about it, but no one is 100% sure. It’s like this weird game of Russian roulette where five of the bullets are you win the lottery, and one is you die. Is it worth the gamble? It looks like they’re going to gamble anyway.

The movie opens with AI actually destroying Los Angeles in a nuclear strike, killing a million people, which is a very ripe metaphor at the moment. Why L.A.? Hasn’t our city suffered enough?

I live in Los Angeles and I was paranoid I was going to have to shoot a lot of material guerrilla-style on my own, so it just made sense to do it in America for that reason. But the second you pick L.A., you’re kind of in the territory of “The Terminator” and things like that.

It gets into a fascinating conversation because, knowing there might be a downside to AI that results in death, at what point would we then not want it? If I said to you that we’re going to have AI in America but the only downside is that 40,000 people a year will be killed by AI, you would say, forget it. But that’s a car — 40,000 people die in car crashes on average every year in America but we still keep cars because the advantages are so strong. I’m sure there are going to be deaths and all kinds of tragic things with AI. But if the advantages are incredible, I don’t have much hope that we’re going to stop it. It would have to be something absolutely horrific on a Sept. 11 level to make us think twice.

The movie paints a future in which robots are sentient, emotional and even spiritual beings who’ve been integrated into human society as co-workers, assistants, civil servants and romantic partners. We’re already seeing an epidemic of loneliness as people are becoming more enmeshed in their technology. Does the idea someone could fall in love with a robot worry you?

No, that doesn’t worry me. I mean, what’s weirder: that someone spends their whole day talking to what might be a sentient AI or talking to a cat, which people do right now? To each their own.

There’s something about human nature to anthropomorphize objects or anything. When I speak to Siri, I say “please” and “thank you,” and with ChatGPT I’m really grateful and trying to talk to it like it’s another person. I think you have to be a bit of a sociopath to not be like that — it says more about you than the thing you’re interacting with. My girlfriend will talk to her car, like when we’re struggling to get up a hill. She calls it Shirley. It’s such a human instinct. I am 100% sure that when they turn up, we’re going to treat them as equals.

How much have you played with ChatGPT? Have you had any particularly unsettling experiences with it?

Yeah, I’m totally fascinated by it. It’s very convincing, like you really feel someone is there talking back to you. I didn’t tell anyone I was doing this but just out of curiosity, I inputted the first sequence from our movie, just copy and pasted the screenplay in, and asked ChatGPT what it thought happened in the film. I gave me four options, and one of them was spot-on. I don’t know if that implies that ChatGPT is brilliant or that I’m a terrible writer. But it was unnerving.

We’re approaching this “Jurassic Park” moment in cinema where, just like CGI changed Hollywood — some would argue not necessarily always for the best — there’s going to be a defining line before and after AI filmmaking. But I don’t think we’re alone. Everyone’s going to be dealing with this.

As we’re speaking, Hollywood is in the middle of a historic double strike of writers and actors in which AI is one of the central issues. What does it feel like to be releasing this movie about AI at a moment when it’s such a contentious issue in the industry?

It’s surreal. When we presented the first drafts of the screenplay to the studio, one of the main notes we got back was, “But why would you ban AI? It’s going to be this amazing tool. Why would anyone want to ban it?” We got that kind of comment from everybody. Now cut to 2023 and the default setting of everyone who comes into the cinema is this feeling of: This is not good for society.

I understand the concern. But if you listen to the guilds, they’re not trying to ban AI. They understand it’s the future and it’s going to be in every single industry. They’re just looking for what they say is consent and compensation, and it’s a fair ask. We’ll see. It’s a very difficult thing to navigate for everybody.

I tend to fit in the camp of getting excited about change and seeing an opportunity. I think if you ask anybody who works in this business, is it perfect? The fact that it costs $200 to $300 million to make a movie — do we want to freeze-frame this moment and keep it forever? I think everyone would tell you no, not really. There’s something not working about where we are.

My secret hope — and it could end up very differently — but my hope is that these tools are going to help democratize filmmaking, that you’ll be able to make anything you can imagine and it won’t cost you tens of millions of dollars. And if you can do that, it will allow for braver filmmaking because there won’t be such a financial risk.

Just like the invention of the electric guitar made it so suddenly everyone in their bedrooms and garages could form bands and we had the birth of rock and roll and one of the greatest periods of music, there’s a possibility that if this amazing tool turns up and everyone can make any film that they imagine, it’s going to lead to a new wave of cinema. Look, there’s two options. Either it will be mediocre rubbish — and if that’s true, don’t worry about it, it’s not a threat. Or it’s going to be phenomenal, and who wouldn’t want to see that?

I actually asked ChatGPT for some suggestions of questions for this interview and here is one it offered: As a filmmaker, you have the opportunity to shape and influence public perception of AI. What responsibility do you feel in depicting AI in a way that balances entertainment with thoughtful commentary and exploration of its potential?

I felt like AI in our movie was real people. Like, whatever nationality or ethnicity you want to label a group of people, I just labeled them AI and then showed their point of view. I think all the problems in the world, when you pull at the thread and you get to the end of it, it’s usually because one group of people are not seeing another group of people’s point of view and vice versa.

I feel quite proud of the movie, in the sense of, if AI ever became conscious and could somehow watch this film, I think they would like it. I think they would be happy. I’m kind of hedging my bets because I feel like, come the robot apocalypse, maybe I’m going to be spared. They will be like, “OK, leave him alone. Don’t enslave him. He understands us.”

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.