Review: In Spainâs âThe Beasts,â brutal instincts flare among small-town residents

You may remember French actor Denis MĂŠnochet as the farmer in the taut opening scene of Quentin Tarantinoâs âInglourious Basterds,â performing opposite Christoph Waltz. Now, after many international roles, including one in Ari Asterâs âBeau Is Afraid,â MĂŠnochet has won a Goya Award â one of the nine that director Rodrigo Sorogoyenâs blood-boiling thriller âThe Beastsâ collected at the Spanish Oscars â for playing a different kind of farmer.

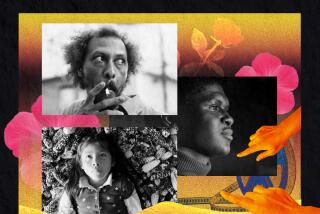

In a desolate Galician town, MĂŠnochetâs Antoine and his wife, Olga (Marina FoĂŻs), grow vegetables to sell and rebuild houses, which they then give away for free to encourage locals to stay, and to entice new people to come. But their efforts go against the longtime residentsâ eagerness to sell their land for incoming wind turbines. Antoine and Olgaâs next-door neighbors, Xan (Luis Zahera), a spiteful drunk who holds court at the areaâs only bar, and his cognitively impaired brother Lorenzo (Diego Anido), are their worst enemies.

Hiding thinly veiled vitriol, the siblings refer to Antoine as âFrenchy,â and invoke Napoleon Bonaparteâs military campaign to conquer Galicia as reason enough to dislike him. Antoineâs mere presence feels humiliating to them: His refusal to sell, preventing everyone else from cashing in, makes him a target.

Acting in two languages, MĂŠnochet initially comes across as a beacon of serenity, his burly build notwithstanding. But that slowly morphs into constant exasperation when the siblings poison Antoineâs crops and taunt him at night. The actor conveys the characterâs growing sense of anger behind a soft expression of masculinity that hopes to protect and do no harm. Heâs at the opposite end of the spectrum from Xan and Lorenzo, ready for a clash.

Still, the Frenchman tries to reason with them over drinks and carries around a small video camera to document his bulliesâ behavior. Olga disapproves of her husbandâs tactics. Whatâs the point of living there if they must do so in fear? Early on, Sorogoyen reveals a frustrating dynamic: The authorities side with the brothers, excusing their behavior as that of simple people who, unlike the worldly Antoine and Olga, have nothing left to lose. The burden of civility, the police claim, falls on the couple.

Thereâs no satisfying resolution in sight for the class conundrum Sorogoyen and his co-writer, Isabel PeĂąa, introduce. Is it fair for these foreigners, well-meaning though they are, to impose their will on several families desperate to escape their miserable circumstances? For those accustomed to abject poverty, even the crumbs being offered the predatory wind-turbine company feel like a life-altering victory.

Antoine and Olga are guilty of gentrifying the place for their loftier dreams of sustainability, yet that still doesnât justify the primal instincts that drive Xan and Lorenzo. As with all great moral dilemmas, Sorogoyen makes it impossible to entirely side with either party without considering that each of them has been victimized by larger social ills.

And thatâs the visceral potency of âThe Beasts,â which suggests that in order to take another personâs life, you have to see them as less than human â or less than yourself. For its second half, in the aftermath of a twist that shouldnât be spoiled, the film takes on an unexpected depth and even a semblance of closure, though it shouldnât be a surprise that no one fully gets what they want.

'The Beasts'

Not rated

In Galician, Spanish and French, with English subtitles

Running time: 2 hours, 17 minutes

Playing: Now at Laemmle Royal, West Los Angeles

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.