Review: The spirit is thrilling, but ‘The Flash’ is weak

- Share via

“The Flash” is a time-travel story and a cautionary tale, a warning of how dangerous it can be to change the past or mess around with alternate realities. There’s some irony in that message, considering the many, many would-be iterations that this superhero saga — a very slow-gestating movie about a very fast man — has cycled through over the past few decades. And now, as this initially enjoyable, increasingly sloppy megabucks mess at last stumbles across the finish line, one has to wonder: Do the decision makers at Warner Bros. and DC Comics secretly wish they could turn back the clock and butterfly-effect one of those earlier versions into existence? Preferably with a different choice of star?

In invoking the much-publicized scandals of Ezra Miller — who anchors nearly every one of “The Flash’s” 144 minutes but has kept a low profile during the publicity tour — I don’t mean to fuel another cancel-culture debate, or to speculate about the convergence of a toxic celebrity and a historically toxic fan base. (Miller has apologized for their actions, citing mental health issues.) Nor do I mean to qualify my admiration for the actor’s witty, fully engaged, nimble-in-every-sense performance. This is hardly the first time a movie’s major PR liability has also turned out to be its greatest creative asset.

None of this will come as a surprise to those who saw the actor’s earlier incarnations of this role in both cuts of “Justice League.” As Barry Allen, a.k.a. the Flash, the calorie-inhaling speed demon in a bright red super-suit, Miller made a divertingly genial goofball — a welcome distraction from some of the hotter tempers and bigger egos of the DC Extended Universe, but also, in a pinch, a handy world-saving ally.

“The Flash,” directed by Andy Muschietti from a script by Christina Hodson, shrewdly keeps Barry in don’t-get-no-respect mode even as it moves this self-deprecating second banana front and center. It begins on a typically thankless morning as Barry, dashing off to work as a forensic scientist at his local police department, is suddenly pressed into top-secret superhero duty. On goes the red suit and off goes the Flash, the world around him slowing to a motion-blurred crawl as he races to handle a crisis in nearby Gotham City that Batman (Ben Affleck), Superman and other Justice Leaguers are too busy, absent or existentially burdened to deal with.

The death-defying, gravity-flouting rescue that follows — involving a crumbling skyscraper, reckless infant endangerment and some awfully dodgy-looking CGI — is something to see, if neither as fun nor as amusing as it fancies itself. As in his recent two-part adaptation of Stephen King’s “It,” Muschietti adopts an exuberantly maximalist approach that’s stronger on energy than finesse. Still, his clever use of ultra-ultra-slow-motion does allow us to experience the ticklish temporal frisson of being the Flash, of moving so swiftly that a split second can stretch out to a leisurely minute. His skills have their charms, too: When potential romance comes a-knocking in the form of a journalist, Iris West (Kiersey Clemons), Barry can tidy up his bachelor pad (but also mess it up again) in record time.

In a sufficiently determined mood, Barry can run so fast that he can reverse the order of time (shades of 1978’s “Superman”). And so he does, returning to a fateful moment from his childhood and — with one tiny course correction — managing to save his beloved parents (Maribel Verdú and Ron Livingston) from a grim, traumatizing fate. Naturally, the laws of cinematic time travel, referenced here in a pretty good “Back to the Future” joke, mandate that Barry’s actions have some undesired consequences. He gets stuck in the past and, clearly not having brushed up on his Robert Heinlein, winds up unwisely joining forces with a teenage version of himself (also Miller, with floppier hair), who’s had a much happier childhood but doesn’t (yet) have the Flash’s superheroic powers.

There’s some cleverness to this gimmickry. It allows “The Flash” to function as a kind of stealthily reverse-engineered origin story, in which Barry effectively shows us — and his younger self — how he gained his powers in the first place. It also allows Miller to give the kind of showily effective double-trouble performance that, whatever you think of it, resists the generally flattening, blandifying effects of the superhero template. Before you can say “grandfather paradox,” the two Flashes are playing a wildly improvisatory game of damage control — one that will send them skittering hither and yon, running through (and sometimes crashing into) walls and pushing the story in bizarre new directions.

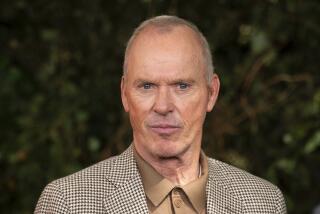

But by new, of course, I actually mean old. In time Barry will seek out the help of his buddy Batman/Bruce Wayne, only to find himself staring into the weary, bedraggled countenance of Michael Keaton. Yes, Michael Keaton, who starred in “Batman” and “Batman Returns” more than 30 years ago, now reemerging from the shadows and into the bright, glaring light of this movie’s alternate timeline. I suppose I could have prefaced that with a spoiler warning, but really, at this stage in the frenzied cycle of superhero-movie overhype, who are we kidding? To hear that Keaton’s Batman appears in “The Flash” is no more a surprise than to hear that the movie was shot in color, encrusted with digital effects and affixed with a useless end-credits teaser.

Keaton’s performance — sly, affectionately cranky, subtly reverberant — is certainly one of “The Flash’s” highlights. But it also reveals, with depressing clarity, the imaginative poverty of the movie’s design. That design will come as no surprise to anyone who saw the recent “Spider-Man: No Way Home,” which brought the series’ past and present superhero incarnations to a point of Marvel multiverse-rupturing convergence. The rival DC multiverse arguably lends itself well to this kind of endlessly self-referential self-revisionism, given all the various incarnations of Batman and Superman, the misfired reboots and flat-out bad movies it’s given us. The dividends are obvious, at least on paper: You the viewer get a nice little jolt of rug-pulling audacity, chased by a satisfying hit of nostalgia.

Really, though, is nostalgia that satisfying anymore? What are the creative gains, exactly, of a sequence that expertly mimics the darkly moody sheen of Tim Burton’s Gotham City, right down to the busy-broody notes of Danny Elfman’s score? Is it worth applauding, as many at my screening did, when actors from earlier DC comic-book epics get dragged into the frame for a few would-be valedictory moments? Does anyone really want to spend more time with General Zod, Michael Shannon’s megalomaniacal dullard from the dreary-ass “Man of Steel”? (To judge by a recent interview, even Shannon himself would say no.)

Zod comes blasting and scowling his way into “The Flash” relatively late, around the same time a somber Sasha Calle soars into the frame as Kara Zor-El, a.k.a. Supergirl. Both Flashes are still there, too, though by that point, even Miller’s light-speed ingenuity has been reduced to just one more element amid a blur of noisy, obliterating action. The most compelling question “The Flash” poses, in the end, has little to do with separating the art from the artist; it’s about whether we can separate the film from the fan service. Lost in an endless game of IP-reshuffling musical chairs, Barry realizes, possibly too late, the futility of dwelling on the past — a fatuous lesson from a movie that can’t stop doing the same.

‘The Flash’

Rating: PG-13, for sequences of violence and action, some strong language and partial nudity

Running time: 2 hours, 24 minutes

Playing: Starts June 16 in general release

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.