20 years later, we look back at a cringeworthy Oscars for the ages

- Share via

Twenty years ago, Rob Marshall’s “Chicago” won six Academy Awards, including best picture, beating out Martin Scorsese’s “Gangs of New York,” Stephen Daldry’s “The Hours,” Peter Jackson’s “The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers” and Roman Polanski’s “The Pianist.” The triumph of “Chicago” — one of several contenders backed by Harvey Weinstein, then at the peak of his power — had been widely expected; so were the wins for lead actress Nicole Kidman (“The Hours”), supporting actor Chris Cooper (“Adaptation”) and supporting actress Catherine Zeta-Jones (“Chicago”).

Less expected: a startling late surge for “The Pianist,” which scored upset victories for lead actor Adrien Brody and director Polanski, whose 1977 rape scandal had resurfaced in awards-season headlines. Elsewhere, Hayao Miyazaki’s “Spirited Away” was named best animated feature, Caroline Link’s “Nowhere in Africa” won foreign-language film and — in one of the evening’s most explosive acceptance speeches — Michael Moore took the stage to receive his documentary feature Oscar for “Bowling for Columbine.”

Times film critic Justin Chang and columnist Glenn Whipp sat down to discuss one of the most cringeworthy Oscars ever and what it portended for the movie industry more than a decade before #MeToo.

Times film critic Justin Chang and columnist Glenn Whipp discuss why the motion picture academy’s choices 20 years ago were far from heavenly.

JUSTIN CHANG: Not to start off on a completely repugnant note, Glenn, but the Oscarcast of March 23, 2003, is forever cemented in my brain as “the Harvey Weinstein Oscars.” That might seem an odd thing to say, since it was hardly the first or last time that Weinstein dominated the Academy Awards race — a race whose over-spending, opponent-smearing, for-your-consideration-or-else modern template he more or less invented. He’d already enjoyed big awards hauls with “The English Patient” (1996) and “Shakespeare in Love” (1998), and he would enjoy them again with “The King’s Speech” (2010) and “The Artist” (2011). But never again would a single awards season feel quite so overstacked with his movies, or — in retrospect — so queasily emblematic of his chokehold on the industry that he bullied, manipulated and abused for decades.

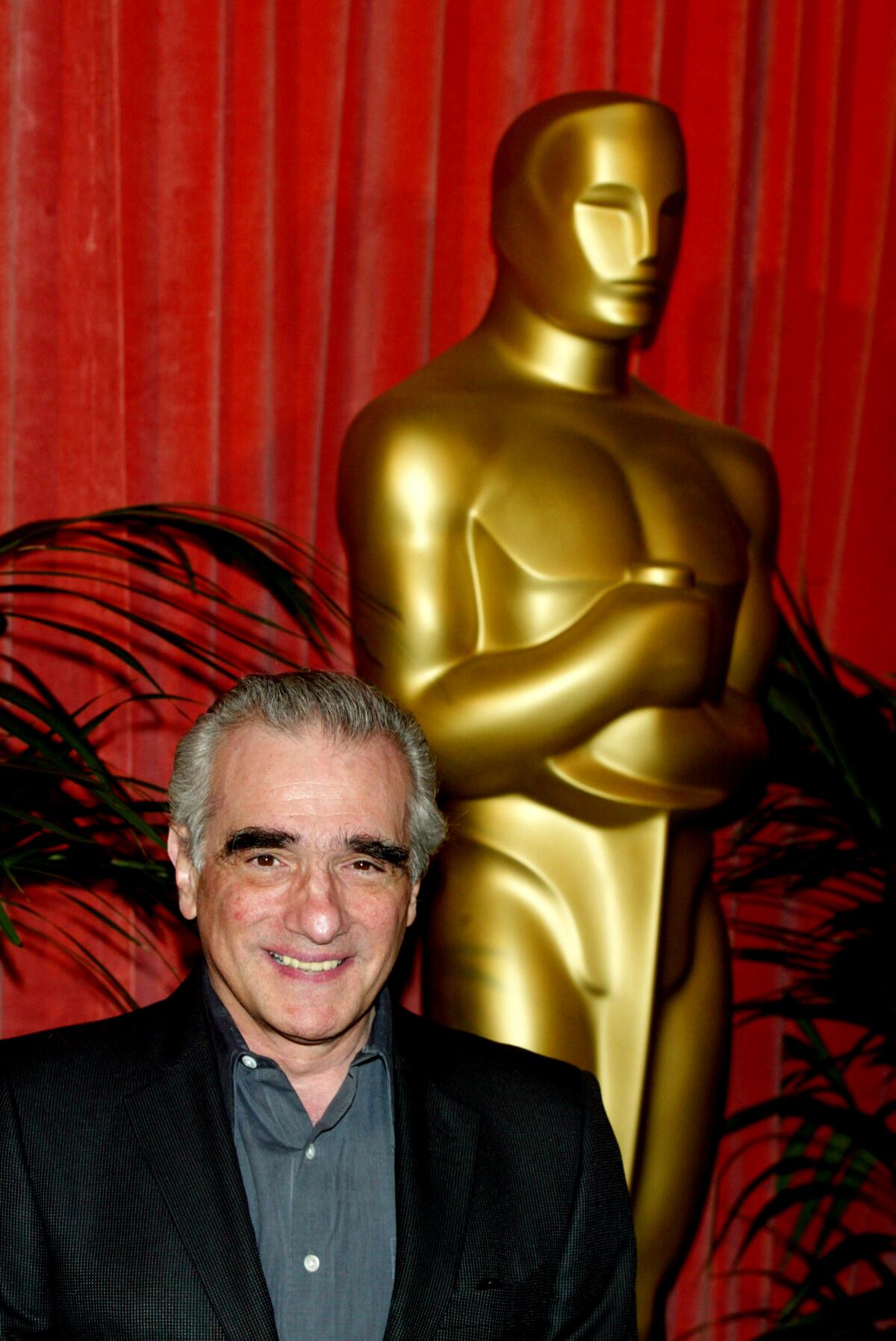

Three of the five best picture nominees — “Chicago,” “Gangs of New York” and “The Hours” — were released by the Disney-owned, Weinstein-run Miramax Films. Of those three, “Chicago” was the dominant favorite all season long. No one was remotely surprised when Rob Marshall’s flashily entertaining Broadway-to-Hollywood adaptation won six Oscars, including best picture and best supporting actress for Catherine Zeta-Jones, so riveting as the murderous chorine Velma Kelly. At the same time, Miramax’s dominance clearly backfired in some respects, suggesting that not even as savvy an awards campaigner as Weinstein could juggle so many favorites. How do you convince voters that “Chicago” is the year’s best movie but also persuade them to cast their director votes for Scorsese — who, at that point, had famously never won a directing Oscar — for the wildly polarizing “Gangs of New York”?

You can’t, and he couldn’t. Once it became clear that this was not going to be Scorsese’s year, nearly everyone assumed the beneficiary would be Marshall, especially after he won the Directors Guild of America’s top prize in early March. But the academy went its own way: In one of the most remarkable single-film upsets in recent Oscar history, Roman Polanski’s “The Pianist” won three Oscars no one was expecting it to win: adapted screenplay for Ronald Harwood, lead actor for Adrien Brody and directing for Polanski himself. That last award was presented by Harrison Ford, who smiled a little smile when he read the name of the filmmaker who’d directed him in “Frantic” (1988). (He certainly looked happier than he did the last time he‘d dropped an Oscar-night bombshell, presenting best picture to “Shakespeare in Love.”)

Polanski wasn’t in attendance, of course, having been a fugitive from American justice since 1978, when he pleaded guilty to having unlawful sex with a 13-year-old girl. Those headlines resurfaced often during that whole awful awards season, and quite a few people, including Polanski himself, decried what they perceived as a Weinstein-backed smear campaign. I suspect Polanski won partly due to a collective backlash against that campaign, and also because of deep admiration for his career in general — like Scorsese, he’d never won an Oscar — and for “The Pianist” in particular. Twenty years later, all this seems both insignificant and momentous: Weinstein is in prison for rape and, having just been given an extra 16 years on top of his existing 23-year sentence, will likely, hopefully die there. His public downfall spurred the rise of the #MeToo movement, and in the wake of that movement, Polanski, still a fugitive, was stripped of his academy membership — though not of his Oscar.

GLENN WHIPP: When we looked back at the 2002 Oscars, Justin, I labeled that campaign season “the absolute worst” and wrote that its “vicious backbiting has not been equaled.” This year, we have the sequel, a sadder and even more sordid season dominated by Weinstein’s obsession with getting Scorsese an Oscar and the ultimate victory for Polanski, a man who, according to that 13-year girl’s testimony, drugged and raped her. He then fled the country, fearful that he’d have to serve additional time beyond the 42 days he had already spent in jail.

The ovation Polanski received that night remains Exhibit A for haters who view Hollywood as a place where morals go to die. It’s a bit more complicated. For one thing, not everyone stood — or even applauded. From the moment “The Pianist” won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, I spoke with plenty of academy members who loathed the idea of rewarding Polanski. The notion that this stance originated as a smear campaign and not a simple declaration of principle is understandable. Weinstein was involved, after all. But it’s also deeply cynical and doesn’t recognize the range of opinions people held.

There were also many who, quite simply, didn’t know (or bother to learn) the facts of the case, and believed, as Weinstein wrote in the Independent, that “whatever you think about the so-called crime, Polanski has served his time.” And, with “The Pianist,” Polanski had just made this shocking, authoritative movie about a Polish Jew surviving the Warsaw Ghetto, guided by his own unflinching memories of enduring the Krakow Ghetto as a child. Should you separate the artist from the art? Some Oscar voters, enough Oscar voters, believed that you should. But that opinion was far from universal.

The motion picture academy’s annual Oscars ceremony worked its way though venue after venue before settling on its current Hollywood home in 2002.

The impulse to give Scorsese the Oscar he should have won for “Raging Bull” and “Goodfellas” wasn’t unanimous either. It’s the exception rather than the rule when people win an Oscar for their best work, unless you think “Scent of a Woman” is peak Pacino. You’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who counts “Gangs of New York” as their favorite Scorsese movie, though I’ll admit to loving its brawls, its spectacle and Daniel Day-Lewis’ fuming brilliance. I could — and did — get behind the idea that it was Scorsese’s time. Looking back, I feel like I became too deeply invested in the “Marty’s due” narrative.

But then, Scorsese did too, turning up at countless events concocted by Weinstein and his campaigners to put him in front of voters. I caught up with Scorsese for a long interview about a month before the Oscars. He sounded tired and ready for the whole thing to be over. After voting began, he endured one last ignominy when it was revealed that a testimonial — one that Miramax was touting in campaign ads for “Gangs” — had been written by an in-house publicist and not legendary director Robert Wise. Academy President Frank Pierson noted that many members asked for their ballots to be returned so they could strike Scorsese’s name.

The ballots weren’t returned. It didn’t matter. Scorsese would have to wait another four years to win that Oscar for the twisty crime drama “The Departed,” a sensational movie that, unlike “Gangs,” would make most fans’ lists of Top 10 Scorsese movies. But just barely.

CHANG: Whichever film(s) you think Scorsese deserved to win for — and I’ll pause to register my displeasure that he wasn’t even nominated for “Taxi Driver” — it’s hard not to feel a certain satisfaction that he won it for a movie that Weinstein didn’t back.

You’re right to note, Glenn, that Polanski’s Oscar win, although widely applauded at the time, hardly amounted to unanimous industry vindication. And yet there’s no denying the heightened #MeToo-era outcry over Polanski’s crimes, especially since several other women have come forward alleging that Polanski sexually assaulted them, in most cases when they were minors. Attitudes have shifted in the U.S., where Polanski was expelled from the academy, and in France, where protests erupted after he won the best director César for his 2019 movie, “An Officer and a Spy.” And this isn’t going away: It’s likely to haunt the reception for Polanski’s new movie, “The Palace,” which might play a major European festival this year, even if it seems unlikely ever to be shown in the U.S.

Separate the art from the artist? We’re not going to settle that debate here, Glenn, but I will note that to try and separate the two would deny the haunting power of “The Pianist” itself. This could be Polanski’s most personal film, a stealth cine-memoir in which his Holocaust survival story merges with that of his real-life subject, the Polish classical pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman. You can’t separate Polanski from it, any more than you could disentangle “The Pianist,” with its galvanizing portrait of German-occupied Poland, from the early Iraq war headlines that were emerging as that year’s Oscars got underway.

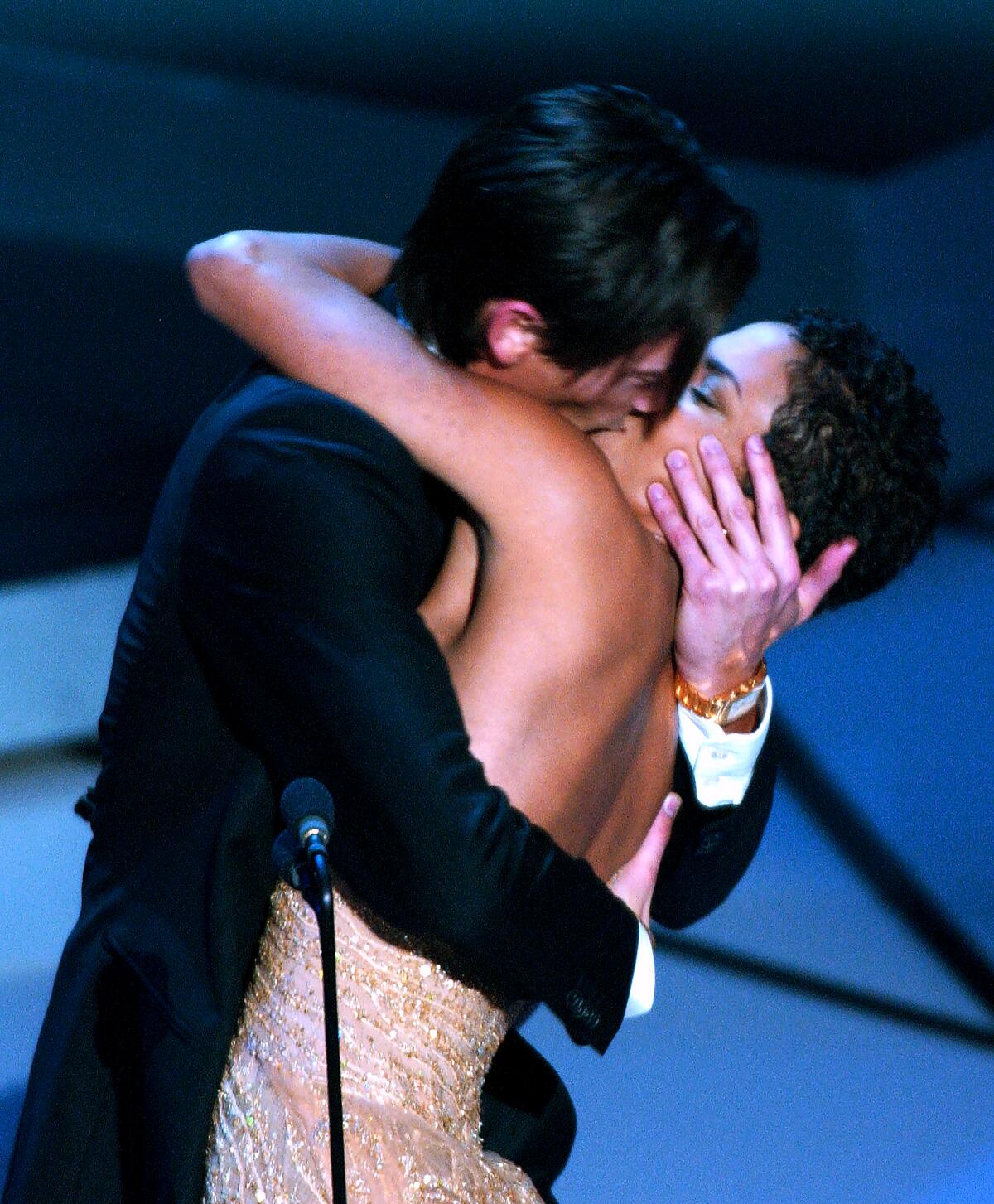

Adrien Brody referenced this in his best actor speech, noting that the film had brought him new awareness of “the sadness and dehumanization of people at times of war” and calling “for a peaceful and swift resolution.” (Brody’s acceptance remains memorable for many reasons, including that infamous kiss he forced on presenter Halle Berry — a moment that drew a lot of cheers and laughs but, to continue with the theme, plays a lot cringier today.) And of course, who could forget the most overtly political moment of the night, when Michael Moore — winner of the documentary feature Oscar for his gun-control polemic, “Bowling for Columbine” — dragged his fellow nominees with him up to the stage and denounced George W. Bush as “a fictitious president” who had led the U.S. into war for “fictitious reasons.” Moore’s speech drew some applause, but mostly a lot of boos, bemused expressions and crossed arms. Unlike some other things from Oscar night 2003, it’s aged pretty well!

WHIPP: I don’t know if I’d go that far, Justin, though I am down with much of what he bellowed from the stage. But then, perhaps I haven’t aged all that well myself. Because as I totter into antiquity, to borrow the words of Peter O’Toole, winner of an honorary Oscar that year, I find I’ve come to cherish the parts of the ceremony that are now distinctly out of fashion. Like ... O’Toole accepting an Oscar from Meryl Streep and eloquently expressing his gratitude, even though he had initially asked the academy to hold off on the honor because he was “still in the game and might win the lovely bugger outright.”

The honorary Oscars have been moved off the telecast, relegated to a separate ceremony, the Governors Awards, a lovely event that celebrates film history, often including the work of artists not widely known to the general public but supremely vital to cinema. (This year’s mix of honorees was sublime: Michael J. Fox, Martinique-born filmmaker Euzhan Palcy, Australian director Peter Weir and songwriter Diane Warren.) It isn’t televised, which means it isn’t rushed. But that also means that it really isn’t seen, which is a shame because these honorary awards are both a benediction and an introduction. When the academy celebrated Alec Guinness in 1979, it revealed the career of an actor I only knew as Obi-Wan Kenobi. As a young movie fan, I dove in.

So it should come as no surprise that my favorite part of the 2003 ceremony came with the 12-minute Oscar reunion, introduced by Olivia de Havilland, that featured 59 Academy Award acting winners seated in four rows on stage. Their names were read alphabetically, starting with Dame Julie Andrews, and each one smiled or waved or blushed or did all of the above — and it was absolutely amazing. Nicolas Cage and then Michael Caine. Luise Rainer, 93, followed by Julia Roberts. Streisand! Streep! Watching it now, I want to cue up “Celluloid Heroes.” It’s a pageant of “people who worked and suffered and struggled for fame ... some who succeeded and some who suffered in vain.”

How did we go from that to a hashtag-driven Twitter poll for a “fan favorite award” and pre-taped Oscar wins? The new academy leadership knows it needs to do better. Justin, let’s check in 20 years from now and see if it did.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.