How to watch every best picture winner from 1960 through 1969

- Share via

The best picture Oscar winners of the 1960s were an eclectic bunch. They consisted of two risqué comedies, “The Apartment” (1960) and “Tom Jones” (1963); four adaptations of musicals, “West Side Story” (1961), “My Fair Lady” (1964), “The Sound of Music” (1965) and “Oliver!” (1968); two historical biographies, “Lawrence of Arabia” (1962) and “A Man for All Seasons” (1966); and one social drama, “In the Heat of the Night” (1967). Also, “Midnight Cowboy” (1969), whatever category that would be in.

How to watch Oscar Best Picture winners through the decades

Intro and 1920s | 1930s | 1940s | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | 2020s (and 2020 nominees)

1960: ‘The Apartment’

33rd Academy Awards — April 1961

Running time: 2 hours 5 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

By playing the most risqué situations with an air of innocent wonderment, writer-director Billy Wilder (“Love in the Afternoon,” “Witness for the Prosecution,” “Some Like It Hot”) gets away with just about everything but murder.

“The Apartment” is a comedy, though it is also, once you scratch the surface, a drama, as any such frank and searching commentary on the morals, or lack of them, in our time would almost have to be. For “The Apartment” is preoccupied with sex and it takes all the boyish charm that Jack Lemmon can summon — and he can summon plenty — to keep us from turning against him.

For Jack, an ambitious clerk with a giant New York insurance firm, “earns” his promotions from the 19th to the 27th floor by lending his walk-up apartment in the West 60s to his bosses for their dates with their “office wives.” He doesn’t quite remember how he got into it — but there it is.

“That,” he shrugs helplessly, “is the way it crumbles, cookie-wise.”

Now, Jack has a crush on Shirley MacLaine, the girl who runs the elevator that takes him to the 19th (et seq.) floor. She is a nice girl and he worships the ground she so seldom walks on. The fifth executive to whom he supplies a key is a top — or at any rate 27th floor — executive. This is Fred MacMurray. (Read more) — Philip K. Scheuer

1961: ‘West Side Story’

34th Academy Awards — April 1962

Running time: 2 hours 33 minutes.

Streaming: HBO Max: Included | Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

“West, Side Story” will be the American picture to watch at Oscar time, for it restores something of the glory that was Hollywood — and Academy voters are a chauvinistic bunch. And glory is the word, even though all of the story takes place amid the bricks and pavements of a New York slum — shot partly “on location,” but mostly in a slum city virtually re-created at Goldwyn studio by Boris Leven.

“West Side Story’s” impact as a stage play was as disturbing as it was shattering, and now everything has been magnified count less times in Panavision 70 and Technicolor on the big screen.

The first impression one gets is that it is all too self-conscious to be real — as, in an astonishing series of views of its skyline from a helicopter, Daniel Fapp’s camera makes all of Manhattan serve as its opening set before zooming down on the school playground where the Jets and Sharks, the “heroes” of our tale, are just beginning to strut their sinister stuff.

As one who had seen the play, I experienced, again, all my original amazement at the intricacy and artfulness of Jerome Robbins’ gravity-defying choreography — but this was still “theater.” Just where I became personally involved is hard to say, but it was probably during the Dance at the Gym, at which Tony and Maria (George Chakiris, Natalie Wood), the Romeo and Juliet of the tragedy, first meet. (Read more) — Philip K. Scheuer

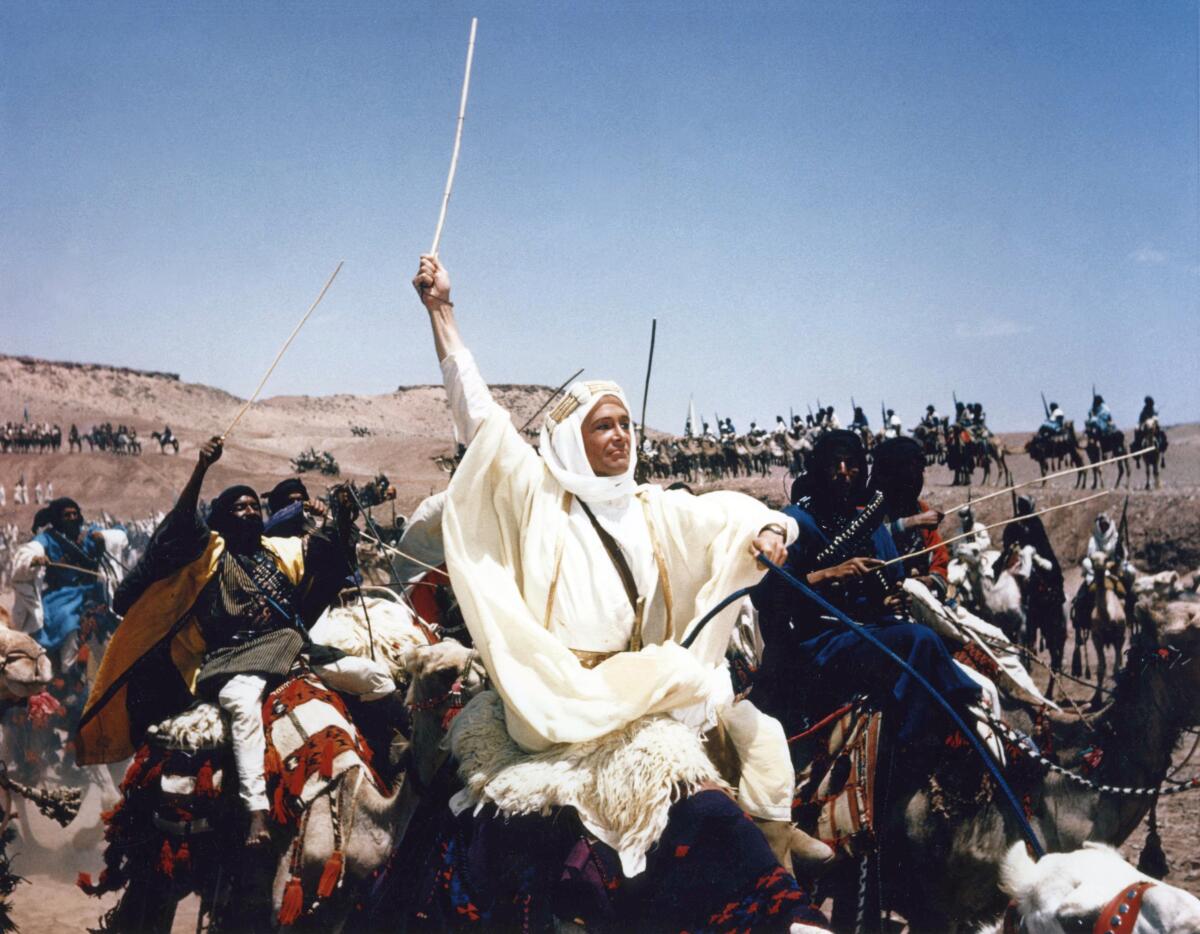

1962: ‘Lawrence of Arabia’

35th Academy Awards — April 1963

Rating: PG (1988 reissue).

Running time: 3 hours 47 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

“Lawrence of Arabia” is the longest picture I have ever sat through if not in temporal time, then in my time. It lasts four hours, counting an intermission. It is also one of the most magnificent pictures, if not the most magnificent, and one of the most exasperating.

You begin to perceive I am filled with contradictions, but in this I have nothing on T. E. Lawrence, the central protagonist of this story, who was known everything from lieutenant to colonel in the British army of World War I and to his Arab friends, of whom there were many, as “El Aurens.”

A Columbia release, it was produced by Sam Spiegel and David Lean (Lean also directed) as a follow-up to their “Bridge on the River Kwai.” This time they sought a fellow who would be at least as “eccentric” as their Col. Nicholson, and found him, beyond their wildest dreams, in Col. Lawrence. Curiously, their version of the Lawrence legend reveals some of the same strengths and weaknesses of “Kwai” — except that it runs at least an hour longer and is infinitely more complex.

Lean has coaxed generally superb performances from his actors and a startlingly versatile one, his first on the screen, from young Peter O’Toole as Lawrence. He is a cross between Alan Ladd and the late Errol Flynn and more striking than either. (Read more) — Philip K. Scheuer

1963: ‘Tom Jones’

36th Academy Awards — April 1964

Running time: 2 hours 1 minute.

Streaming: HBO Max: Included | Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

Astonishingly faithful to Henry Fielding’s classic, the British-made “Tom Jones” was adapted by a not-quite-so-angry John Osborne and directed by that hitherto modern realist Tony Richardson. Even so, it is bawdy, bellicose, sprintingly acted and photographically arresting. An ever-increasing band of devotees is, equally loudly, already proclaiming it a masterpiece. Unquestionably, it is 1963’s dark horse.

“Tom Jones” wallows in the lowest instincts of its people — instincts that are hysterically emotional and unfailingly gross and brutalizing when they are not simply carnal. And Tom — as portrayed with an irresistible joy of living by Albert Finney — makes him as much rogue as saint, as much devil as blond angel. It is a narrow tightrope he walks indeed.

“Tom Jones” re-creates its period magnificently. It is all the best and the worst of British humor, from Chaucer to Coward — with excursions that suggest Shakespeare, Chaplin, Hogarth, “Oliver Twist,” “The Threepenny Opera,” “Jules et Jim” and what-have-you. Richardson and his associates have superimposed on it just about every trick of the trade since the flickers began — silent technique, complete with subtitles; images speeded up by undercranking; stop motion; spoken asides to the audiences; irises and wipes, and everything from hand-held cameras to helicopters. (Read more) — Philip K. Scheuer

1964: ‘My Fair Lady’

37th Academy Awards — April 1965

Rating: G (1970 reissue).

Running time: 2 hours 53 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

Following some beautifully flowered titles, “My Fair Lady” went into the opening action in Convent Garden as raucously as the stage play does, and I had some misgivings about it since all this seemed even more hopped up in stereophonic sound than in person. But after a few more sequences I told myself that this $17-million movie decidedly deserves a yes verdict.

In the delicacy of George Cukor’s direction and the playing of Miss Hepburn as Eliza and Rex Harrison as Prof. Higgins, I felt a more cutting poignancy, something closer to the original “Pygmalion,” than in the theater.

Then, later still — I think it was the expression of touchingly desperate defiance on the face of Audrey Hepburn as she finally enunciated “The Rain in Spain Stays: Mainly in the Plain” — my estimation jumped to “great.” And when the curtains came together at the finish of just three hours, three hours of Technicolored enchantment, I heard myself all but echoing Col. Pickering’s proud summation of Eliza Doolittle’s performance as a duchess at the Embassy Ball, “a total triumph.” (Read more) — Philip K. Scheuer

1965: ‘The Sound of Music’

38th Academy Awards — April 1966

Rating: G (1969 reissue).

Running time: 2 hours 54 minutes.

Streaming: Disney+: Included | Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

“The hills are alive with the sound of music ... “

Piercing the rolling mists, the camera enters a Grimms’ fairyland of jutting peaks, verdant valleys and castled lakes, floating down and down and stopping at last only when it catches up with Maria, in the spritely, sprightly person of Julie Andrews, dancing and singing her heart out and indeed bringing the hills alive.

It is in this magical manner that Robert Wise’s airborne camera approaches fabled Salzburg, just as it descended on the skyscraping jungles of Manhattan — and another Maria — in “West Side Story.” It is an auspicious, thrilling introduction to “The Sound of Music,” the motion picture, which Wise has adapted to the medium from the last of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s stage musicals, taking this sweet, sometimes saccharine and structurally slight story of the Von Trapp Family Singers and transforming it into close to three hours of visual and vocal brilliance, all in the universal terms of cinema. (Read more) — Philip K. Scheuer

1966: ‘A Man for All Seasons’

39th Academy Awards — April 1967

Rating: G (1971 reissue).

Running time: 2 hours.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

If only because it expands the audience from hundreds of thousands to millions, the motion picture of “A Man for All Seasons” would be an occasion for rejoicing. Here, surely, is the finest “classic” play — certainly the finest in the English language — bestowed on the world in the 1960s.

The film comes to us under equally fine auguries — and auspices. Robert Bolt made his own adaptation, Fred Zinnemann directed it and the English-American cast, headed by Paul Scofield in the role he originated, that of Sir Thomas More, has been impeccably chosen.

The motion picture is so professional, so brilliant an intellectual exercise and so moving an emotional one, so superior to the average “special” that it seems almost crippling to state that I believe Bolt and Zinnemann could have made it greater than it is. I have the feeling that Bolt was almost too severe with himself as a writer, even though he has come up with a completely no-waste screenplay of two hours. (Read more) — Philip K. Scheuer

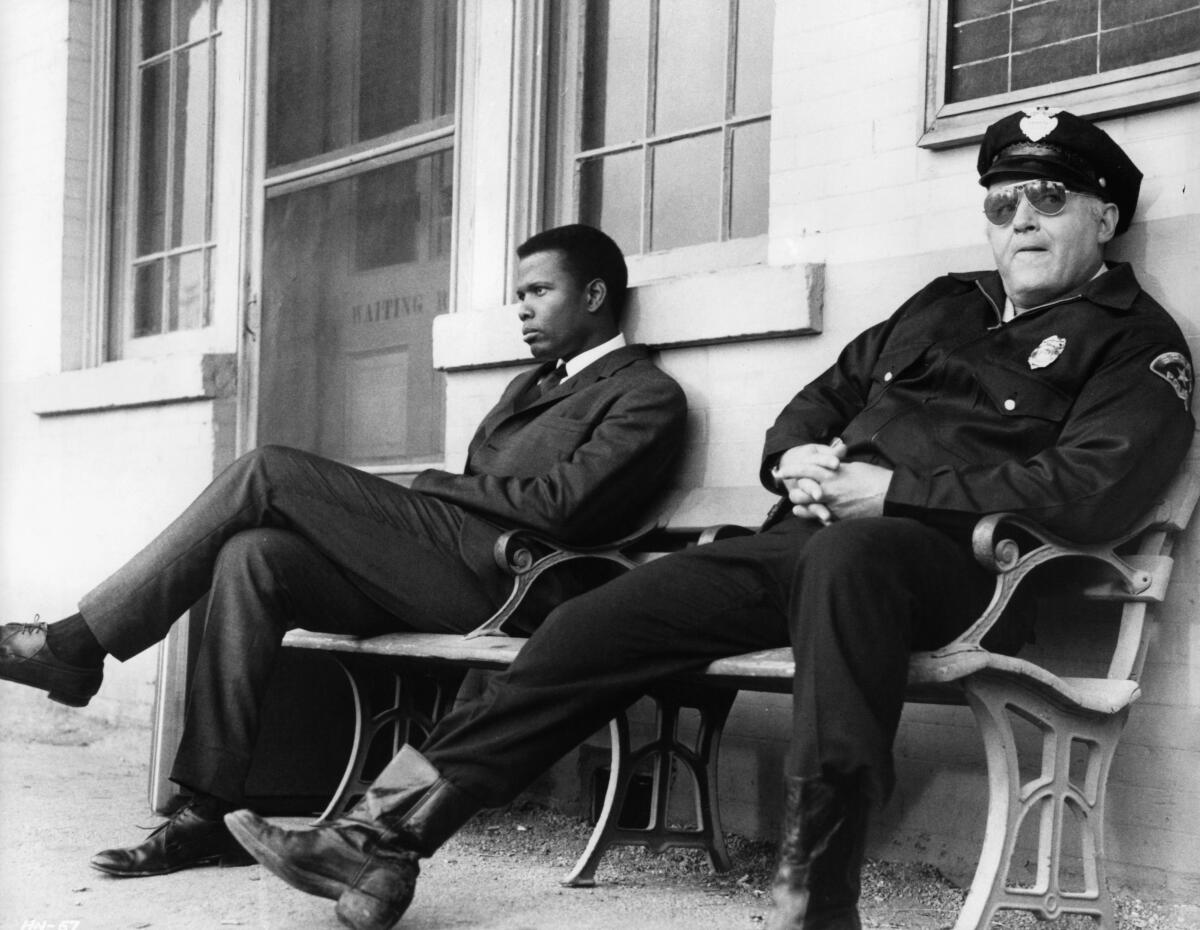

1967: ‘In the Heat of the Night’

40th Academy Awards — April 1968

Rating: PG.

Running time: 1 hr 50 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

Sydney Poitier stars as a Philadelphian visiting his mother in the old hometown of Sparta, Miss. There’s an important murder. He’s an early suspect, only because he’s wearing money and a suit in a region where Negroes presumably do without either.

The confrontation with Rod Steiger as a potbelly, gum-chewing tough sheriff is cruel and funny. The lovely surprise is that Poitier is a homicide dick, and a good one, persuaded to, dissuaded from and re-persuaded to help the sheriff (who wouldn’t know a bruise from a .45 exit wound) solve the crime.

But what we’re after is the confrontation of Negro detective with a southern town reluctant (defiantly) to believe that any Negroes anywhere have stopped saying yassuh boss and shufflin’ along. They have, and the confrontation is often marvelous. (Read more) — Charles Champlin

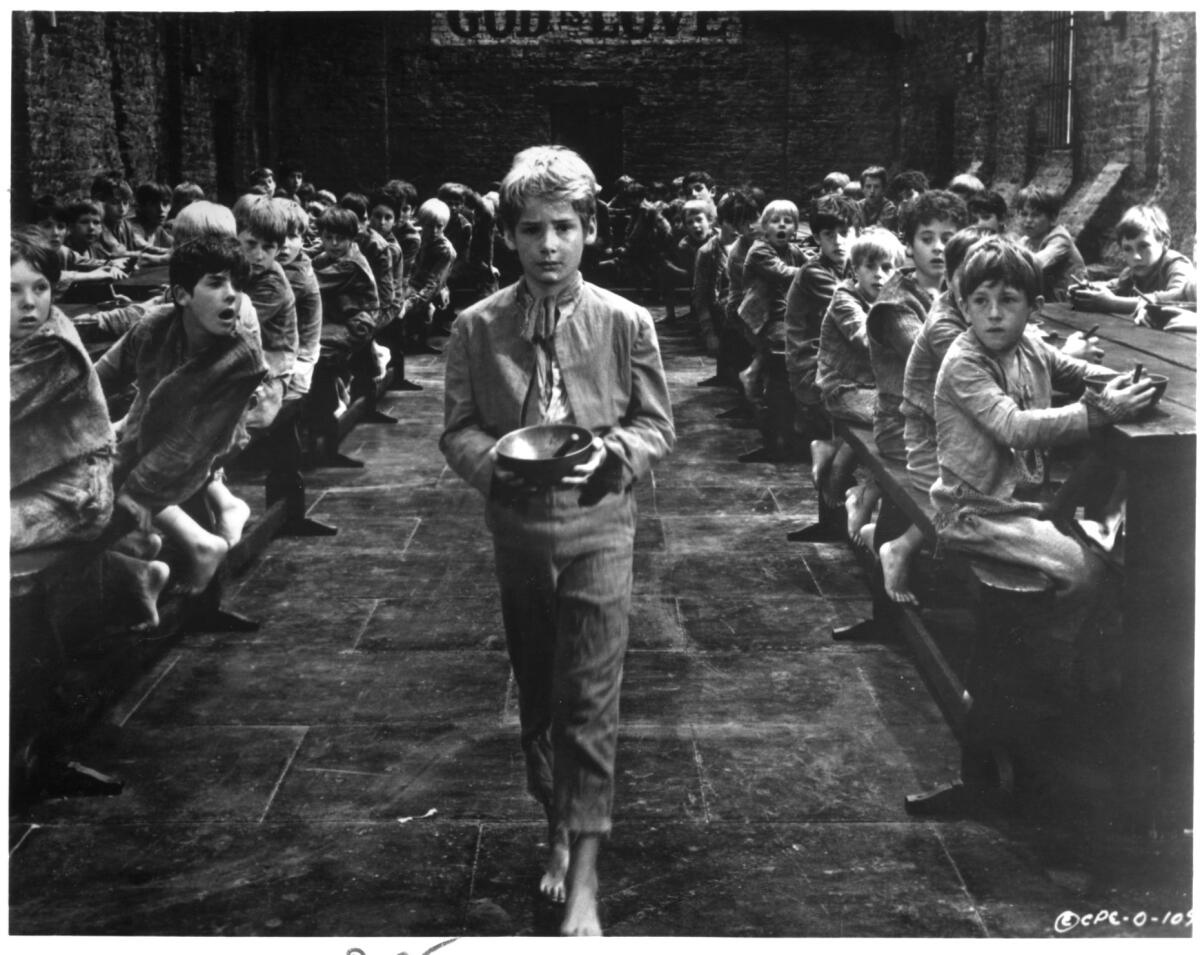

1968: ‘Oliver!’

41st Academy Awards — April 1969

Rating: G.

Running time: 2 hours 30 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

No small part of the bouncy charm of “Oliver!” is that the snakes in the grass have all the lines. Having stolen everything else in sight, the well-known Anglo-Saxon villain, Fagin, and his pint-sized sidekick, the Artful Dodger, also steal the picture. It’s just that all the world loves a rascal, and Ron Moody as Fagin and young Jack Wild as the Artful Dodger are as artful and rascally a pair as you’ll meet in a good while. In their shreds and tatters and patches, they have joie de vivre as well as larceny in their hearts.

Oliver Reed as Bill Sykes is thoroughly malevolent and scary (admirable as an actor, entirely hissable as a villain). And Mark Lester as Oliver Twist is a picture of cherubic and attractive innocence, exuding likability with every quavering line. And Shani Wallis is entirely sympathetic as a fallen good girl who untwists a bad life heroically.

“Lavish” is a lavishly overused word, but there’s no getting away from it in talking about this big, bright, expensive Columbia musical. (Read more) — Charles Champlin

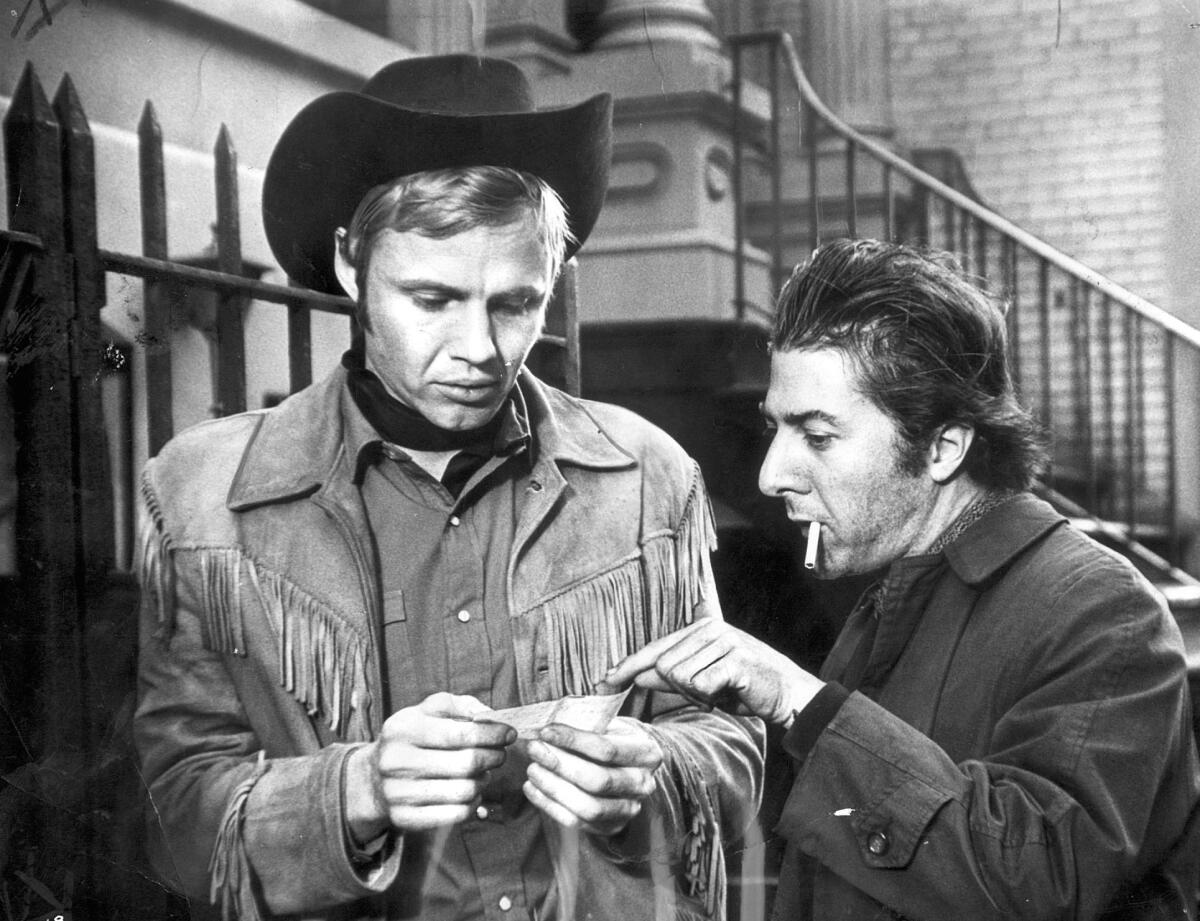

1969: ‘Midnight Cowboy’

42nd Academy Awards — April 1970

Rating: R (1971 reissue).

Running time: 1 hour 53 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

What ought to be said right away, because it’s easy to forget it after the fact, is how radically “Midnight Cowboy” differs from a certain set of expectations we might have had for it. The story of a good-looking blond buck from Texas fired with simpleminded dreams of making it as a stud hustler in Manhattan could easily have become another of the gamy sexual permutations which the screen is so earnestly examining for us these days.

But John Schlesinger’s film is instead an invariably moving study of unlikely (and unsexual) friendship and of collaboration for survival in the sad and greedy shadows cast by the bright lights of Times Square.

Dustin Hoffman as Ratso, a gimpy Bronx Italian who could hardly be further away from the world of “The Graduate,” creates a character so whole, so convincing, so singular, that it takes no little effort to remind ourselves that the same actor was also the collegian in pursuit of Catherine Ross and Mrs. Robinson.

Newcomer Jon Voight as Joe Buck, the refugee dishwasher from a Texas beanery, is so powerfully persuasive in his high pitch drawl and cowboy costume that you read with disbelief he is a product of Yonkers, N.Y., and a Texan only for Schlesinger’s purposes. Voight is in fact a major addition to the family of important American actors and his portrayal of a good-hearted lunk who life has kicked around pretty good and who tries to create one myth so to pursue another, is damn near perfect. He is sensitive and insensitive, childlike and all too adult, comical and pathetic. It seems clear that Voight and Hoffman discovered their characters together, and revealed them through speech which often has a just found, improvisational quality. (Read more) — Charles Champlin

How to watch Oscar Best Picture winners through the decades

Intro and 1920s | 1930s | 1940s | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | 2020s (and 2020 nominees)

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.