Review: ‘Sidney’ celebrates Poitier’s legacy, but does not go deep enough

- Share via

Sidney Poitier, who died in January at age 94, shouldn’t have been the only Black leading man of his talent, magnetism and stature in his Hollywood heyday, when all the firsts were his. But with the civil rights struggle and his hard-won stardom amplifying each other, he damn sure showed what the solo version of such breakthrough greatness could do.

At one point in “Sidney,” Reginald Hudlin’s documentary about the groundbreaking actor-director-activist, we see him in a later-days interview admit to having felt lonely at his top. The wealth of feeling that one moment hints at is something you wish were more richly explored in a bio-doc about someone whose history-chiseled impact is as complex as they come. But an Oprah Winfrey-produced movie celebrating the icon who meant the most to her — and showing her breaking down on camera as she expresses that — is not likely to be the venue for more rigorous contemplation.

For your safety

The Times is committed to reviewing theatrical film releases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because moviegoing carries risks during this time, we remind readers to follow health and safety guidelines as outlined by the CDC and local health officials.

At first, however, it’s Poitier himself talking to us through Hudlin’s camera, and it’s mesmerizing. His memories of being a Bahamian farm boy unfamiliar with cars or mirrors, of first facing American racism as a Miami teen, and of battling illiteracy and poverty to get into New York’s American Negro Theatre, are told with such snap, care and detail he becomes his younger, discovering self all over again. We’re reminded that the acting greats never seem to lose their storytelling power.

When Hollywood called (starting with “No Way Out” in 1950), the dignity, strength and charm of his roles uplifted Black moviegoers, while never threatening whites. Poitier still had to sacrifice freedom to save a racist (“The Defiant Ones”) and help German nuns to secure a historic Oscar (“Lilies of the Field”), but he frequently broke barriers in on-screen representation and off-screen power.

In his biggest movie year, 1967, he memorably slapped a supremacist in “In the Heat of the Night” — a moment rightly relished on-screen by interviewees Spike Lee, Morgan Freeman and Louis Gossett Jr. But a more militant Black citizenry was already labeling Poitier an Uncle Tom, even with his noteworthy and, we learn from one activist, personally endangering commitment to the civil rights movement. As Lee puts it, Poitier suffered the “slings and arrows” Denzel Washington didn’t have to, but thankfully he had the shoulders for it.

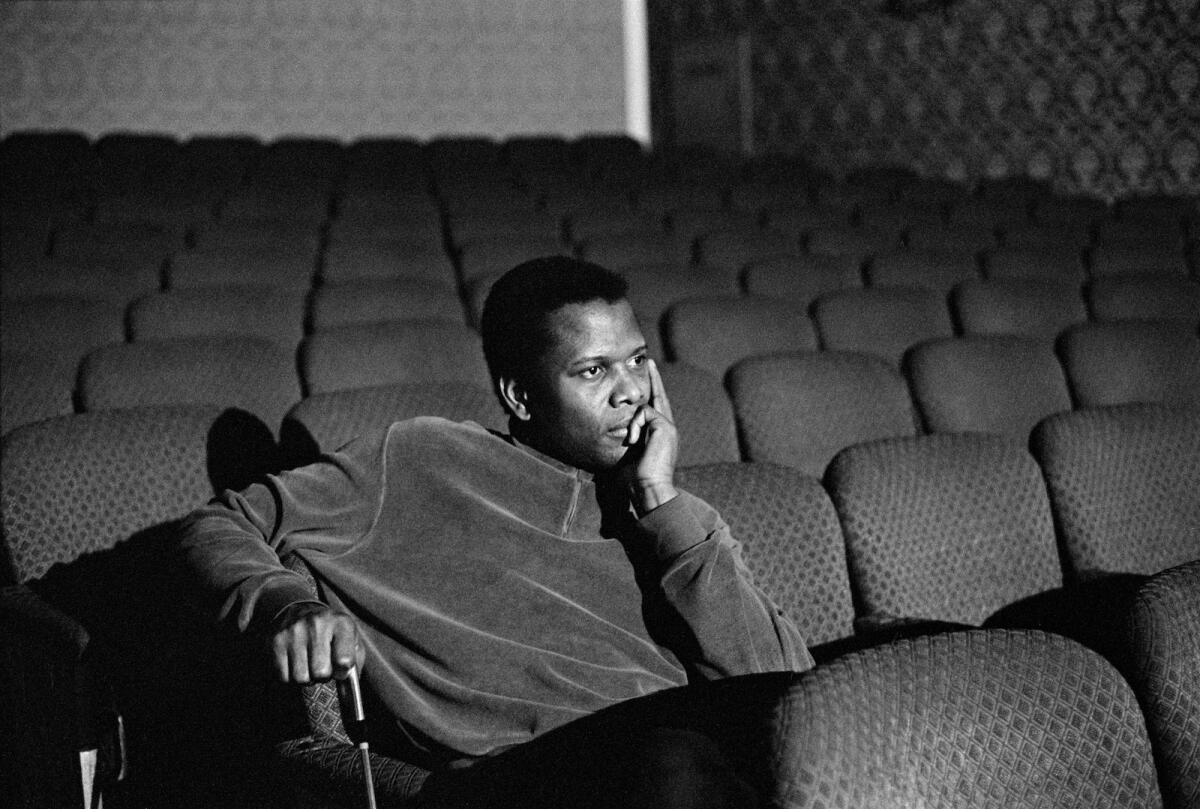

A tribute to Sidney Poitier, with love.

Though his turbulent affair with Diahann Carroll (his “Paris Blues” co-star) is addressed — including recollections from his first wife, Juanita Hardy — the bulk of coverage of Poitier’s family life is devoted to how he cherished the example of his parents, and how he committed to responsible fatherhood, eliciting warm memories from all six daughters and widow Joanna.

Much of “Sidney” plays like an Intro to Poitier class or a slick tribute for fans. The greatest-hits approach sometimes disappoints, though, when we know how artful and challenging the nonfiction form can be since James Baldwin came alive in “I Am Not Your Negro,” and the docu-series “The Last Movie Stars” revealed an achingly human Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward.

Here, the rhythm is of talking heads and archival footage in respectful harmony, balancing spirited A-list salutes (including Washington, Quincy Jones, Barbra Streisand and Halle Berry) with cultural insights offered up by writers Nelson George and the late Greg Tate, who speak to the hoped-for and never-enough contours in Poitier’s career, which was be-all when it counted most, as when he hired majority Black crews for his directing projects.

There is surely more to be mined from this extraordinary, complicated trailblazer’s life than one suitably enjoyable love letter to his brilliance and bravery. The story of his lively, passionate friendship with Harry Belafonte — this movie’s richest personal vein, spanning theater, politics and movies (all hail “Buck and the Preacher”) — could be its own documentary. So here’s hoping “Sidney” sparks deeper looks, rather than sealing the life off from further reflection. There’s plenty of time, after all, because while we may have lost the man this year, his towering legacy “carrying other people’s dreams” — how he once described it to Winfrey — will endure on as few others can.

‘Sidney’

Rated: PG-13, for some language including racial slurs, and some smoking

Running time: 1 hour, 46 minutes

Playing: Starts Set. 23, Laemmle Royal, West L.A.; also available on Apple TV+

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.