- Share via

For 50 years, Haile Gerima has been a beacon for genuine independence, free both from the strictures of the film industry and the constraints of conventional storytelling.

The Ethiopian-born, Washington D.C.-based director emerged in the early 1970s as part of a group of filmmakers from UCLA who would come to be known as the “L.A. Rebellion” movement, including Charles Burnett, Jamaa Fanaka, Larry Clark and Julie Dash. Gerima would go on to distribute his movies himself.

This weekend marks the beginning of a series of tributes and celebrations for Gerima, including the Netflix debut of a new 4K restoration of his 1993 film “Sankofa,” a time-traveling story of Black resistance during the era of American slavery, which begins streaming Friday. “Sankofa” will also screen for free Friday at Ava DuVernay’s Array Creative Campus in Los Angeles, with Gerima’s 1982 movie “Ashes and Embers” playing there Saturday.

Also Saturday, Gerima, 75, will receive the inaugural Vantage Award at the opening gala for the new Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, honored alongside Sophia Loren, recipient of the Visionary Award. (DuVernay, an academy governor, is also a co-chair of the gala.)

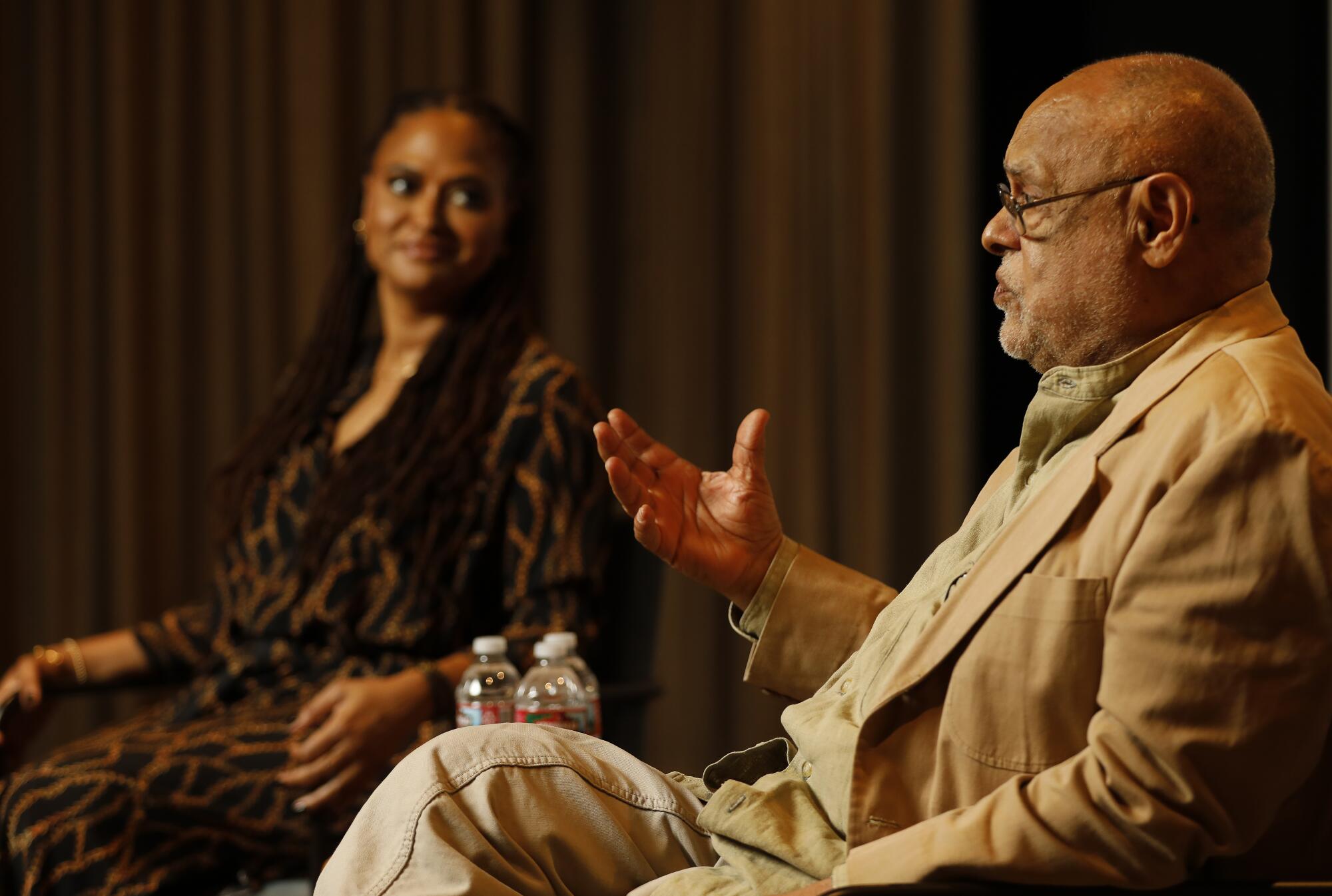

The museum will host the screening series “Imperfect Journey: Haile Gerima and His Comrades,” through Nov. 14, which will spotlight his work along with that of colleagues and former students. Gerima will attend the series launch Oct. 2 with a screening of “Sankofa” and a panel discussion moderated by DuVernay and also including Bradford Young, Raafi Rivero, Daniel E. Williams and Gerima’s wife and collaborator, Shirikiana Aina.

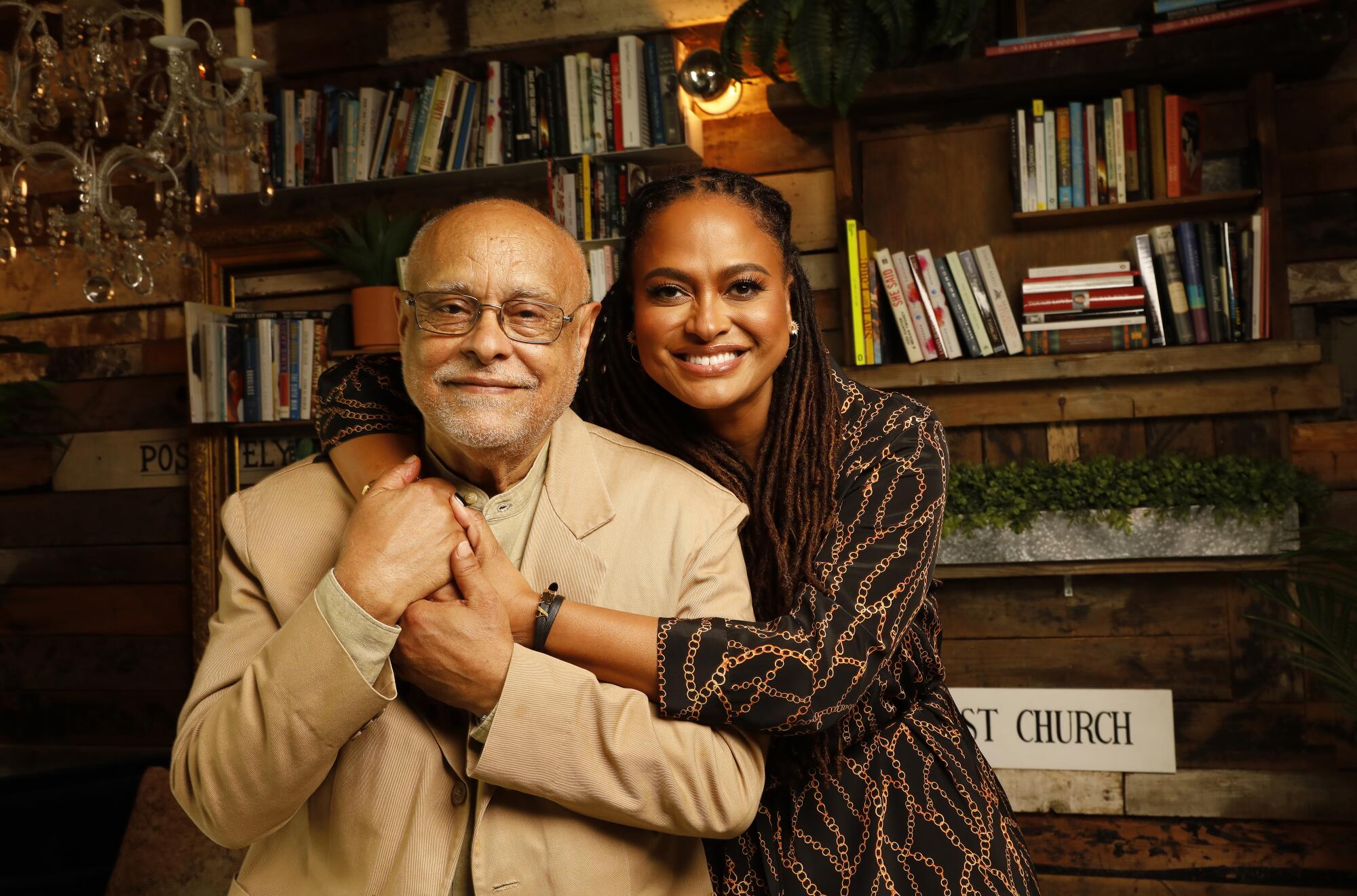

This week, Gerima and DuVernay sat for an interview in the theater of DuVernay’s Array Creative Campus, the compound in Los Angeles’ Historic Filipinotown that functions as the center of operations for her production company, distribution collective, nonprofit work and other endeavors. It was directly inspired by Gerima’s own Sankofa bookstore in Washington, D.C., where he was a longtime teacher at Howard University.

The two have a warm rapport of mutual admiration, with DuVernay affectionately referring to Gerima as “Maestro.” Fitting, since he’ll teach the first-ever master class at the Array campus, with 15 students selected from more than 500 applicants participating over five days.

“It’s so important, because he could have just come and done the academy thing,” DuVernay said of the master class. “I just think it’s really telling for him at this point to continue to be teaching and continue to be trying to build perspectives outside the norm.”

What does it mean to be getting this recognition from the academy, with the award and retrospective?

Haile Gerima: For me, it’s the work of people I feel sincerely respect what I attempted in my whole imperfect expressions in film. At the same time, I think Ava is key in this whole thing. In fact, that’s why I’m accepting it. She knows to this day, I have a lump in my throat, because I’m fundamentally against Hollywood; anything coming near it gives me a heart attack because it’s over 100 and something years of a history of exclusion. It has excluded Native Americans, yet it demonized them. Africans demonized by them. Every attempt by African American filmmakers that tried — they were invalidated by this white supremacist judgment and judication of racism. And so I come with this whole history in me, and I always kept away from it.

So the issue now, and I think the struggle too, is — is it sustainable? Ava unconditionally embraced me for a long time. I have a second life as a filmmaker because of her. I’m very energized thinking about how she respects me and how she honors me. But is it sustainable? Is it going to be another [example] of white Americans’ fragility and guilt and then suddenly we are dropped? Every 20, 30 years, these things occur. And so that’s my only concern...

Ava was saying to me, the idea is to create inclusionary film preservation that democratizes the idea of cinematic expressions globally. Not only for white Americans but globally.

As the Academy Museum’s chief artistic officer, Jacqueline Stewart will be in charge of screenings and events, giving the past relevance in the present.

Ava DuVernay: The Academy Museum feels independent of the academy itself ... the academy is self-described trying to shake off some old stuff, based on pressure, and that privilege and the ways in which they’ve operated before. But the Academy Museum was always a separate group of people that had a mandate to go just do the best you can.

And [museum Director] Bill Kramer, I think he turned the thing around, because it’s very intentional about making sure that museum was inclusive of more views of the world than is the Hollywood view. So when that was the conversation and they were talking about honorees, I was like, “Well, this is not a conversation unless you’re talking about Haile Gerima.” “Who?” Not Bill Kramer, but many other people [asked], “Who?” Well, then I was like, “The fact that you’re asking ‘who?’ is the answer to why he should be there.”

I just began educating people to who he was and why it was so important. If the Academy Museum is saying this is what we stand for — not necessarily voices that have been authenticated and validated by the Hollywood studio system, but everyone — then you need to start with an artist who strikes against the very heart of the Hollywood system. So they really embraced it. It was not a hard sell.

As a shrine to the Oscars and, more important, a tribute to the movies, the new museum is at its best when it sidesteps the obvious.

Ava, when did you first encounter his movies, and what have they come to mean to you?

DuVernay: I went to UCLA. And there’s a cadre of filmmakers that came out of UCLA that are often spoken about in the Black student community there. That’s when I first saw “Sankofa.” My cinematographer at the time, Bradford Young, who was actually a student of Mr. Gerima, gave me a more up-close view of Mr. Gerima — and his teaching and his personality and what he believed in — that went beyond just me seeing the films.

Eventually, I met him, and I met him again until he remembered me. And would always carry him with me as I made my work. But the biggest piece of it — the films are gems, who he is is singular — but for me, the transformative piece of his journey was his distribution and management of his films. That has changed my career path from being someone who was at the mercy of studios and distributors to someone who very early on said, “Oh, I actually don’t have to do that. There’s another model. I’ve seen it. It’s been done.”

I stand on his shoulders. He did it. That’s what AFFRM [the African-American Film Festival Releasing Movement] was early on — which is now Array — which was the idea that you could self-determine what happens to your film.

Even further to when I first visited Sankofa bookstore, I thought, “I want this.” I want what he calls “liberated territory,” his own space to show what he wants, play what he wants, say what he wants, read what he wants. And you can come there and do that. And that’s where we’re sitting, right?

[The Array campus] is an extension of seeing ... “We can have our own space? Oh, I want that too.” And so, thank you. Thank you so much.

Gerima: She’s trying to make me cry. I’m trying to stay no-crying Haile.

Tell me about taking that step in particular. What was it like realizing you had to take back the distribution apparatus and put the films out yourself?

Gerima: For Black filmmakers, Chicano and Native American filmmakers, you have no choice. It’s all hostility you meet. Finishing a film is a war. When you finish a film, the next war is the neglect, the uninterested, the so-called industry that tells you your mother’s story is invalid, it’s not a story. And that’s where we come from. So nobody should have the illusion of thinking that’s also not our responsibility.

When I finished UCLA, I just wanted to be a filmmaker. But I realized we graduated into a desert and white kids graduated into an industry. Even if they all didn’t make it, there was an industry for them to go to. For me, Charles Burnett, Larry Clark, all of us coming out, we were in a desert. Literally. That’s the only image I can tell you.

So when I went to Howard, my partner, my wife and me decided to distribute African and African American filmmakers. At that time, I even had an independent distribution company who took my films, but it was a very unfair distribution. So we started distributing. [It was like], “Let’s experiment and see what we could do.”

Out to prove that Black film before Spike Lee is not a monolith, Maya Cade’s platform showcases more than 250 movies by Black creators and where to watch them.

When people talk about your work, a phrase that comes up often is “decolonizing cinema.” I think that really comes through in “Sankofa,” with its matter-of-fact mysticism and time travel. It’s not typical cinematic storytelling. Is that idea of decolonizing cinema something that exists both in the storytelling, in the movies themselves and in the way you get them out to the audiences?

Gerima: You see what happened especially in Hollywood and the over 100-years history of Hollywood — the white supremacist grammar of aesthetics of storytelling is the dominant factor. It’s amplified by the three-act play itself, that formality itself coined by teachers. When I was at UCLA, it was just something convenient for producers, but it has nothing to do with the art of storytelling.

When I first came to the film school, I’m surrounded by the upheavals of Black people, the Black Power movement, the Black Panther Party, the African liberation movement, Latin America. But in that I noticed the battleground was story. Everybody’s war and conflict begins from story. Who owns your story? Who tells your story? And then to tell your story — you can tell it the uniform way, in the dominant way of what a movie is, but you could also liberate yourself from that paradigm and say, “What would my cinematic accent be?”

To tell you the truth, the first revolution I waged was against my own colonization. It started colonizing me in Ethiopia — Tarzan movies, John Wayne movies. This is at home, a small town. I was confronted by everything. Even your idea of desiring a girlfriend is contaminated by these movies’ empowering of blond hair, blue-eyed women. It affects all over the world. So I made a film called “The Death of Tarzan.” Since I worshiped Tarzan, for me to begin to liberate my vocabulary, my accent, I have to kill Tarzan in my head.

I realized we were all there in that film school — Black folks from America, from Africa, Latin America, South Americans and also Chicanos, Native Americans who dared to be in a film school in a world that made them so nonexistent in their own land. We all responded to African films. We responded to Latin American films, because Latin Americans are the first to say cinema is for them the new hydrogen bomb ... it erases ideas and implants new ones. It doesn’t only erase, it implants.

Ava, in thinking about the influence of Mr. Gerima on you in particular, you’ve recently moved away from cinema into more television work — is that because you felt excluded from moviemaking in these same ways?

DuVernay: Oh, no. No. I don’t feel like I was excluded. I mean, I’m included as much as is palatable for the current structure. I just found more freedom in television ... I saw my heroes having many years between their films and saw that television allowed for the building of a muscularity, just with pace. I could keep practicing, keep telling stories, keep writing, keep going. If I’m making 12 episodes of “Queen Sugar” — or right now we have eight shows, it’s a little too much — but to be constantly on set, constantly on the floor, I feel like I’m getting better. And I’m writing a film right now. I’ll be making a film next year.

But what does it take — two, three years just to see how it feels to be every month on the floor with various projects? And right now, television and streaming allows for creators like me to be able to do that ... And in terms of the telling of story on set, command of the crew, all of those things — with “Wrinkle in Time,” where I lost my way with that, I was working with a very big studio, really nice people, but it was making film by committee and I decided, “No, I need to go away to a place where I can just do my own thing for awhile.” That was television.

And Mr. Gerima, your 1975 movie “Bush Mama” is playing as part of the retrospective, and as it opens, you and the film crew are being harassed by the Los Angeles police at gunpoint. How did you come to get that footage and what made you include it? It’s outside the story of the movie, but it so clearly conveys the world the film is depicting. It’s an astonishing moment that is frequently written about, but I’ve never heard you address it.

Gerima: Sometimes there are accidental gifts. We were shooting. We rented a police car, fake guns, etc. My cameraman is in the character’s apartment, in the window with the camera. And suddenly, police surrounded us. We could have died. There’s a short policeman behind me with a gun straight on my back and one on the driver of the car. And then this guy coming with a gun out does not see the short policeman behind me.

The short policeman says to me, “Get your permit.” I said, “Sir, don’t create confusion, please. We have a permit.” And I went to my pocket and that other guy says, “Take your hand out of your pocket.” [It] almost created a confusion of disaster. Five, six people were about to die, guns pointed at them.

My film is really about the police state creeping into Los Angeles ... and police crime is not really taken seriously. The police come seemingly to protect you, but it’s really empowering itself. And so I said, “This is how the film should start.” It’s like there’s not even a freedom to be filmmakers ... Not free to even be storytellers. There’s a lot of connotations to be read in it. I felt it’s a gift the L.A. police gave us.

A filmmaker, playwright and novelist, Melvin Van Peebles was an influence on generations of artists with audacious, rebellious movies such as “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” and “Watermelon Man”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.