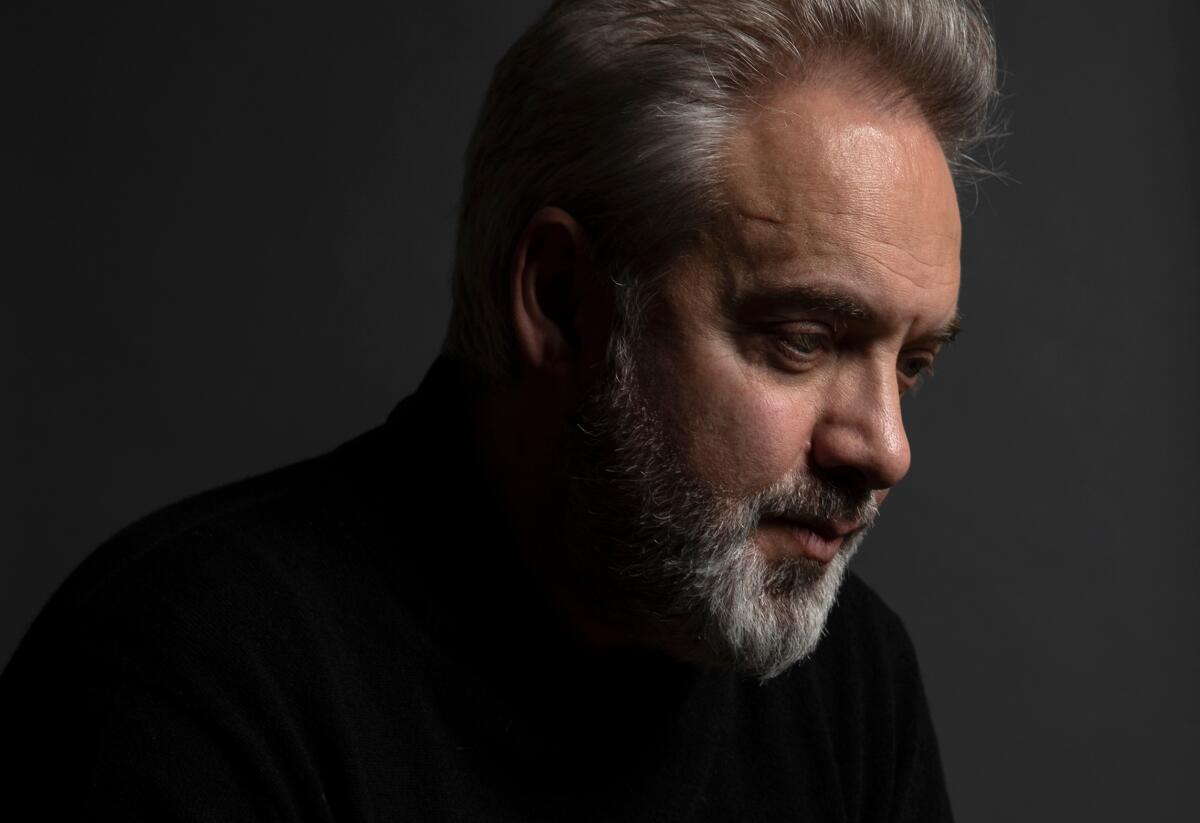

Hollywood doesn’t often make films about World War I. Sam Mendes’ ‘1917’ is a rare exception

- Share via

Growing up in England, Sam Mendes always wondered why his grandfather Alfred seemed to be constantly washing his hands. One day he finally asked his father, “Why does Granddad do that silly thing with his hands?”

Mendes’ dad explained that, having served as a young soldier in the First World War, Alfred could still vividly recall the terrible muck and mire of the trenches. Even after all those years, he still felt a compulsive need to try to get himself clean.

“I remember that shocking me then, that 70 years later, he would be unable to forget,” Mendes, 54, said on a recent afternoon in Los Angeles. “And it still does in a way now.”

Mendes’ new film, the World War I epic “1917,” is dedicated to his grandfather and the millions of men like him who fought in the Great War, both those who died and those who could never wash away the memories. Opening in limited release on Christmas, smack in the heart of awards season, before going wide in January, the movie follows a pair of British soldiers, played by relative newcomers George MacKay and Dean-Charles Chapman, as they attempt to deliver a message across enemy territory to stop an attack that is sure to end in disaster.

Both in style and substance, “1917” is perhaps the boldest gamble yet for Mendes, who made his feature filmmaking debut 20 years ago with “American Beauty,” which won five Oscars including best picture and director, and who most recently directed the James Bond films “Skyfall” and “Spectre.” Made to look as if it were filmed in a single, unbroken take, “1917” attempts to blow the dust off a chapter in history that feels remote to most moviegoers, telling a universal story of sacrifice and heroism through the experience of two brave soldiers on a deadly mission.

“I’ve made this movie for as big an audience as possible, not for people who understand history,” Mendes said. “It’s not a history lesson or ‘Eat your peas and cabbage.’ You’re trying to articulate some larger truth. It’s when human beings are pushed to their absolute limit that you begin to understand a bit more about the human experience: what it is to walk hand-in-hand with death, to not know whether you’re ever going to see your family again, to have your friend die in your arms.”

With a $90-million production budget and the marketing muscle of Universal Pictures behind it, “1917” is aiming to follow a similar path to that of Christopher Nolan’s World War II picture “Dunkirk,” which became a somewhat unlikely box office smash in 2017, earning $525 million worldwide and scoring a best picture nod.

“Sam and I are both huge fans of ‘Dunkirk,’” said Pippa Harris, Mendes’ producing partner. “Sam had already been thinking of doing this movie for years. But it certainly gave us confidence in terms of knowing there was an audience out there for a more thoughtful war film that was thrilling but also had something to say.”

Although “Dunkirk” is just the latest in a long line of successful Hollywood films about World War II, “1917” is charting a lonelier path. World War I casts a significantly smaller shadow in American culture than the Second World War, which claimed the lives of four times as many U.S. soldiers. Comparatively few movies about the Great War — 1957’s “Paths of Glory,” 1981’s “Gallipoli,” 2011’s “War Horse” — have broken through with audiences in a major way since the 1930s.

To filmmakers, World War I also presents particular difficulties in dramatic terms, from the lack of an enemy as clear-cut as the Nazis to the very nature of the fighting.

“It’s a war of paralysis and it’s very static,” said screenwriter Krysty Wilson-Cairns, who cowrote “1917” with Mendes. “It’s three years of sinking in the mud 300 yards from the enemy. There’s mud, there’s trenches, there’s blood — and that’s kind of it.”

In the stories his grandfather Alfred had told him about carrying messages through no man’s land on the Western front, Mendes saw a way to make a different kind of World War I movie. Drawing on first-person narratives, diaries and letters, Mendes and Wilson-Cairns drafted a script that they then took around to the major studios.

Mendes knew that in today’s risk-averse Hollywood, a large-scale period movie set more than a century ago with no American actors, no pre-sold awareness and no franchise potential was not exactly a slam-dunk. “We’re in this weird place now where movies are either $250 million or $20 million or below — and the movies like this and the movies that I’ve made before, with the exception of the Bond movies, don’t really get made,” Mendes said.

Throw in that war movies aren’t generally considered appealing to women and often don’t perform strongly overseas and the pitch was that much tougher. But Steven Spielberg — who produced Mendes’ “American Beauty” and “Road to Perdition” and made his own World War I film, “War Horse,” in 2011 — saw the movie’s potential, and his Amblin Partners signed on to make it.

“Steven said, ‘This is going to work — you’ve got to do it in the way you want to do it and just go,’ ” Mendes said. “There was no pressure of ‘You’ve got to cast stars.’ ” He chuckled. “They did say at one point, slightly nervously, ‘It would be nice to have a few faces in the movie we recognize, just for audience comfort level.’ ” (Colin Firth, Benedict Cumberbatch and Mark Strong were cast in supporting roles as military leaders. “Game of Thrones” veteran Richard Madden and “Fleabag” breakout Andrew Scott pop up too.)

Constructing a film that would play as a single, unbroken, real-time shot required a monumental amount of planning and precise choreography for Mendes, cinematographer Roger Deakins and the rest of the cast and crew. “Very few sequences were shorter than five minutes,” Mendes said. “I think we went to 10 minutes at one point, which is pretty long. There was one eight-minute take that we did 56 times. Those were the moments you just thought, ‘Oh, God. Why am I doing this to myself?’ ”

Despite the pressure of being front and center in his first big movie, MacKay quickly learned how to navigate the production’s high-wire act. “All that technicality became muscle memory more than anything,” said the actor, who had a supporting role in the 2016 dramedy “Captain Fantastic.” “Of course, there were some takes where in the last 30 seconds the rifle slips off your shoulder and it nullifies the rest of it. But we’re all human and we all had those moments, so we all understood it when it happened.”

For Mendes, the goal was less to wow the audience with the film’s formal audacity than to deliver an immersive, visceral cinematic experience. “I didn’t want it to feel ostentatious or gimmicky,” he said. “We decided we never wanted the camera to go through a keyhole or follow the path of a moving bullet or pass through a wall or fly 2,000 feet in the air. I didn’t want the camera to draw attention to itself.”

Mendes knows that for audiences, “1917” is a far different sort of proposition than, say, a Bond film. There will be no action figures or video game tie-ins. There will be no “1918” sequel.

Whether or not the film earns critical plaudits or racks up year-end awards is secondary to Mendes. (“I haven’t read reviews since before ‘American Beauty,’ ” he said.) In the end, all he really hopes is that moviegoers will take a chance on a story that for a couple of hours rescues men like his grandfather from the sepia tones of history books and places them up on the big screen alongside superheroes and “Star Wars” characters.

“There aren’t many of us who have the energy to push this ... thing up the hill, but I think that for those of us who can, it’s important that we do,” Mendes said. “You know, we’ve built these palaces for ourselves. They’re comfortable, the sound is unbelievable, you’ve got huge screens and bells and whistles: IMAX, Dolby Vision, Dolby Atmos. Let’s use the damn things.”

Sam Mendes’ harrowing long-take thriller “1917” follows two young British soldiers through the trenches of World War I.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.