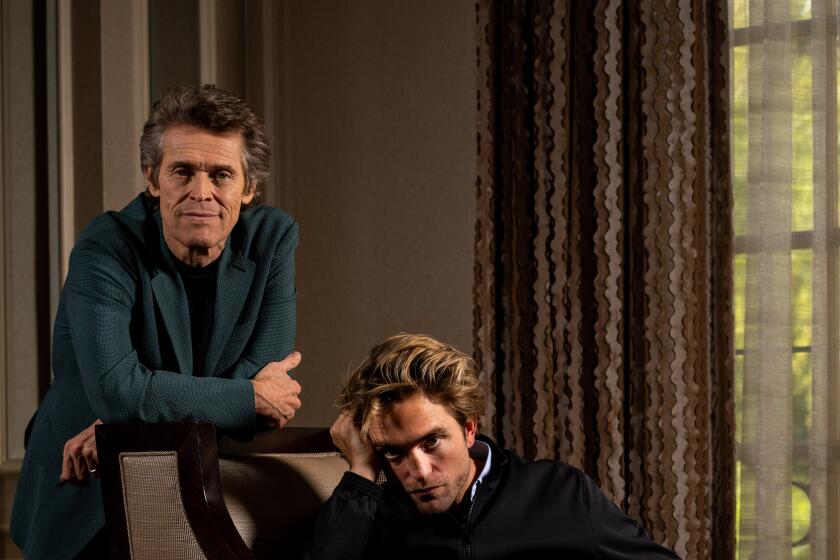

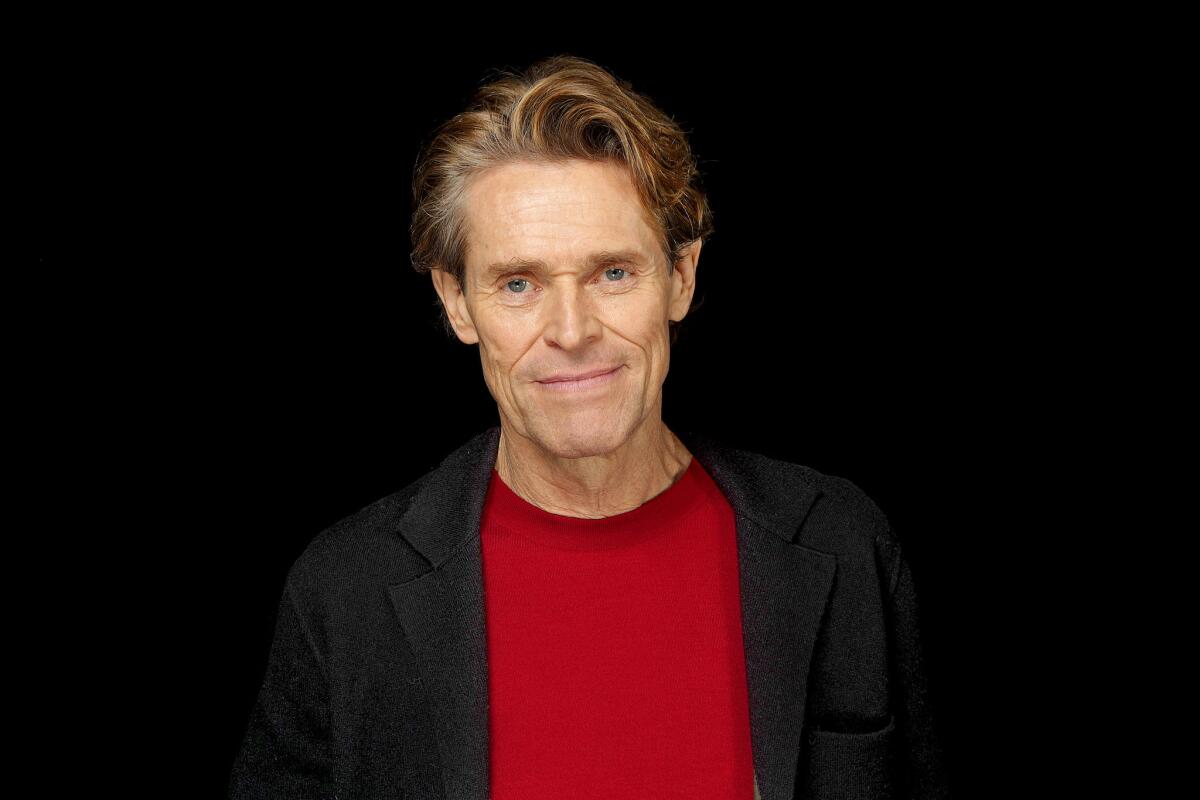

Willem Dafoe can tell which of his films fans have watched as they approach him

- Share via

New York — Willem Dafoe seems to have always been with us. Wisconsin-born, he came up through New York theater and got sacked from his first film gig — 1980’s “Heaven’s Gate” for, as he once noted, laughing during a quiet moment on set. He’s gone on to appear in more than 100 movies since and now it’s hard to imagine a part he couldn’t play, given the opportunity.

Dafoe has four Oscar nominations — “Platoon” (1987), “Shadow of the Vampire” (2001), “The Florida Project” (2018) and “At Eternity’s Gate” (2019) — but no wins. Perhaps that will change this year with his intense turns in “The Lighthouse” and “Motherless Brooklyn.” And even if not, there’s no doubt that he’ll continue to work, because that’s what he does.

He spoke with The Envelope at A24’s New York offices about the fever dream of a film “The Lighthouse,” forging relationships and feeling useful, always.

What attracted you to working with Robert Eggers on his “Lighthouse” script?

I saw “The Witch” [Eggers’ first feature]. Then I took my wife to see it the next day. And then I said to my representatives, “I’d like to meet this guy.” When I see a film I admire, if a guy’s open to it — or a woman — I like to cultivate a relationship with them.

And then you saw “The Lighthouse” script?

It was a beautiful script. Beautiful, elevated language with a beautiful music and rhythm. We were going to shoot out in nature, in the elements. So that appealed to my sense of adventure. There was no question — I had no questions. He gave me all these beautiful videos and interviews with lighthouse keepers, old vintage footage. And tapes of the accent. We found our way through and arrived at this West Country English accent for my character. It’s the only thing that sounded good to my ear — this kind of pirate accent.

It’s kind of gutsy, to go all out with what starts out sounding like an old-timey pirate. But you make it work.

It was written in that dialect; that’s the rhythm. Accents are funny — you want them to be rooted but you don’t want them to be academic, because then they die. We had a dialect coach on the set who helped Rob [Pattinson] and me with our accents. And there were so many external things to play with, not only an accent but an extreme look. Those teeth!

You often stick with directors you like — you’ve done multiple films with Paul Schrader, Wes Anderson, Lars von Trier and Abel Ferrara. What makes you stick with the familiar?

Sex dreams about mermaids, ill-tempered seagulls who seem possessed, flatulence employed as “deliberate displays of power.” Robert Eggers’ black-and-white thriller “The Lighthouse” has much to discuss.

You’ve cultivated a relationship, and you also enjoy working with each other. Also, you need to be able to not have it be about you all the time. Some people will do a lead role with a director and then on the next project, when they ask them to do a cameo or a supporting role, they say, “No, that’s going backward for me.” I said, “Well, that’s not a concern.” I like being part of the fabric of a director’s work. Because you feel relaxed, you can go deeper. Part of working on it is knowing what color or animal you are.

Do you think you’ve had a freer career than some actors because you’ve been able to play all those different colors?

Freer? I don’t know; sometimes it’s lonely out there. You don’t think about career, you think one at a time. I also think that when you’re attracted to directors, that sustains you over time.

You once said that you got into acting because it was a good way to meet people, or girls — but when you got older it transformed. What did it transform into?

You feel useful, you feel like it’s your calling. It’s a way to train yourself. A way to learn how to be a human being. Performing is a wonderful vehicle for becoming a better human in an active way.

Are you more of a human being today than you would have been if you’d not been an actor?

I think so. Because you get to consider different perspectives. And you also challenge your sense of self. You challenge the identity you create all the time. You’re always dismantling it, trying to disappear and consider someone else’s condition. If you feel useful, you can disappear into it. You don’t feel stuck.

Years ago, Janet Maslin described you as looking “perfectly villainous.” Did that bother you, early on, that critics — maybe others — were comparing how you actually looked to being a terrible person?

In the beginning, if you’re not conventionally handsome or conventionally charming, the most interesting character roles are villain roles. I have participated in that, because I was leaning on that as a screen persona. When you’re young, you’re trying to plant the flag — so you’re lucky if you get to plant that. Then people are sticking you to that point and you think, “Oh my God, this is not good.” But with time, I felt like that sort of evaporated. It’s funny; when you’re on the street and people come up to you, I can almost tell what films of mine they’ve watched by how they approach me.

Some genuflect — you did, after all, play Jesus in “The Last Temptation of Christ” — and some run away?

I mean, maybe I’m deluded that I have different responses. Not that versatility in itself is a great thing. But it’s nice to know you aren’t peddling something, that you’re working with something that’s a living thing and you’re using yourself as material to be transformed. … You do it for yourself but also as a person in the community who gets up in front of the fire and tells the story or inhabits the thing. I respond to that function. Then I feel useful. And I don’t feel guilty about not being in Africa saving people from famine.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.