- Share via

Last March, when filming on the dystopian thriller “Hard Matter” was underway, reporters descended on the movie’s various sets along Mississippi’s Gulf Coast.

Inside the stately Oak Crest Mansion Inn in Pass Christian, a correspondent for the local TV station WLOX interviewed actor Frank Grillo. On WXXV-25, the Fox and NBC affiliate, an anchor told viewers “a famous actor could be seen around Gulfport,” referring to Harvey Keitel, Grillo’s co-star.

Downtown Gulfport had been transformed into a post-apocalyptic battlefield for the movie about a despotic corporation that had taken over America’s prison system, replacing law enforcement with criminals. The mayor’s office put out a statement warning residents not to panic if they heard gunshots in the area around city hall, as one reporter explained, “It was all make-believe.”

Latavius Powell, founder of Gridiron Productions, the movie’s main investor, now says that it wasn’t just the plot that was make-believe.

In a recent federal lawsuit, he is accusing independent producer Bret Saxon of bilking Gridiron investors out of $5.05 million and leaving the film in limbo.

Powell alleges in the suit that Saxon, his producing partner Jeff Bowler and their company Wonderfilm falsely claimed that Mel Gibson would star in the film and used Gridiron’s investment to secure a $2-million state tax rebate that the producers diverted “for their own purposes.” They added that the pair were “seasoned con-artists in the movie business.”

Saxon’s attorney, John Schlaff, has called the claims “false — and demonstrably so,” and cited communications to disprove Powell’s claims. He blames Gridiron and the director for problems with the film’s production and alleged that Powell had “threatened Mr. Saxon with dredging up his past in an attempt to “extort a settlement from him.” Powell’s attorney says the claim was “pure fiction.”

Over the last 13 years, Saxon and companies he has controlled have faced various accusations of fraud, racketeering, and misappropriation of funds involving multiple films where he served as producer or executive producer, according to a Times review of court filings and interviews with investors and former associates. He settled several of these cases — others were dropped or dismissed — but in one he was found liable for fraud and breach of contract and was ordered to pay $2.25 million to one of his investors.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

In fact, the “Hard Matter” case is among at least 14 lawsuits filed against Saxon or his companies since 2010 — the majority of them stemming from investors seeking more than $13 million in investments, loans and fees. Some accused Saxon of using film funds to bankroll his “luxury lifestyle” — including making a down payment on a $4.2 million Pacific Palisades estate, which he has denied. Others alleged he enticed investors by telling them he had the rights to adapt books about major figures such as Tupac Shakur and that on projects, he inflated budgets only to pocket the difference.

In 2011, The Times wrote about Saxon and his role in allegedly diverting money from several film productions. Saxon at the time denied any wrongdoing and said he was the victim of extortion in at least one case.

The complaints against the producer and former attorney have persisted.

In 2018, pop singer Jessica Simpson sued Saxon and Bowler, accusing the pair of engaging in a “conspiracy to extort millions of dollars.” The case was settled.

Three years later, the State Bar of California disbarred Saxon, citing “clear and convincing evidence the respondent is culpable for the intentional and dishonest misappropriation of the investor’s funds, an act of moral turpitude.”

The action was sparked by a court ruling that Saxon had misused a film investor’s funds.

Schlaff said that while Saxon “admits he made mistakes” and is “sorry for his role in the dispute,” other lawsuits against his client were “opportunist meritless copycat litigations.”

Saxon is a successful businessman and producer who, at times with Bowler, has made 20 films “without legal incident, many of them critically acclaimed,” Schlaff added.

Saxon’s long history of litigation provides a glimpse into the murky and freewheeling world of independent film financing, where deals are often made based on handshakes and relationships with little oversight.

Long a draw for outside investors, indie films are also known to be ripe targets for the naive and inexperienced newcomer, especially as the rapid shift to digital and streaming productions has created more investment opportunities.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Some of Saxon’s former investors and associates are surprised that he has continued to make movies despite all the litigation.

Steven Zellers invested nearly $2 million on several of his film projects between 2004 and 2008 and says he spent four years suing him unsuccessfully to recover his money. He later settled his litigation.

“It’s funny how this guy has literally not changed his playbook whatsoever,” he said.

Saxon’s attorney declined to comment on the settlement.

Buddy Wyrick, a vice president for Wonderfilm, which Saxon co-founded, said the producer is a “devout Christian” who is being unfairly maligned.

He said Gridiron’s Powell “is trying to validate his lawsuit with Bret’s past. And I think that’s a shame.”

‘The guy sells the dream’

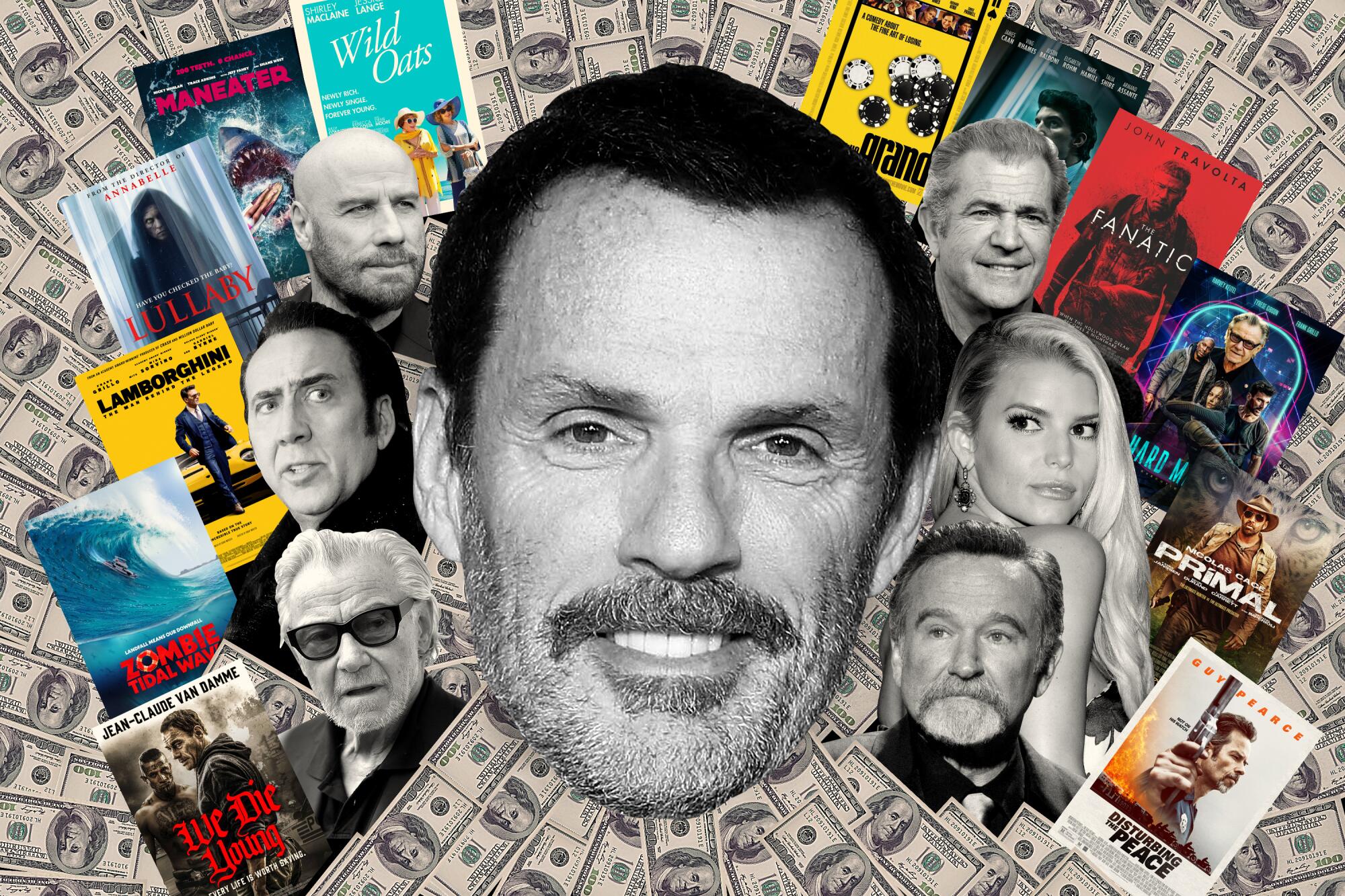

Saxon, 58, is a prolific producer with credits on nearly 30 films and TV projects such as the reality series “Inked” (another eight are in various stages of development and production, according to IMDb.com).

Earlier this year, L.A.-based Wonderfilm announced a partnership with Mark Wahlberg to produce a documentary and feature film about fitness guru Jack LaLanne. (Wahlberg has since pulled out of the film project following the publicity surrounding the Gridiron lawsuit, Schlaff said.)

Saxon’s oeuvre leans toward mostly B-list, low-budget film titles such as crime thriller “The Ritual Killer” starring Morgan Freeman and “The Fanatic,” a horror movie featuring John Travolta. None are box office hits. The 2019 action thriller “Primal” starring Nicolas Cage has to date grossed only $228,679 on its $18 million budget, while last year’s “Lamborghini: The Man Behind the Legend” collected $1.7 million in ticket sales, according to IMDb.

Saxon exudes charm and over the years has presented himself to investors as a wealthy, multi-hyphenate success as an author, attorney, entrepreneur and Hollywood producer, according to court filings and interviews with former investors and associates, most of whom declined to be identified out of fear of retaliation.

It was only after they had shelled out money, they allege, that they discovered Saxon was given to hyperbole.

Saxon attorney Schlaff disputes the characterization, saying that his client prides himself as being “optimistic” and “pragmatic.”

Recently, Bowler‘s biography on IMDb.com stated that Wonderfilm launched a partnership with director Michael Bay and producer Brad Fuller to develop and produce multiple projects for Universal. However, a representative for Bay’s production company said the parties have had discussions over a single idea but there is no deal.

After The Times inquired about the purported partnership, its reference no longer appeared on Bowler’s IMDb.com page.

“The guy sells the dream,” said one former colleague.

Saxon burnished this image with swagger, dropping important names and surrounding himself with pricey accessories. He lived in a five-bedroom, eight-bathroom, 8,100-square-foot Pacific Palisades estate with a home movie theater, tennis court and swimming pool; he boasted about how he traveled on a private jet often with his personal trainer in tow, while at home he employed a nanny, tennis coach and housekeeper.

“Saxon talked extensively and ostentatiously displayed his exotic collection of Italian and German automobiles, his Black American Express card, and his employment of an entourage of support staff ‘to keep things running,’” stated one lawsuit.

But even as Saxon portrayed himself as an accomplished producer, he faced financial and legal woes.

Saxon grew up miles from the glitz and glamour of Hollywood, in Los Alamitos, an Orange County suburb. He developed an early fascination with celebrity, crashing premieres and red carpets while he was in high school with his friend Steve Stein.

The two later wrote “How to Meet and Hang Out With the Stars: A Totally Unauthorized Guide” that is filled with images of Saxon alongside the likes of Jerry Seinfeld, Sylvester Stallone and Tom Hanks.

In 1985, at 19, he was arrested on two charges, a criminal felony and a misdemeanor in Los Angeles County — one involving grand theft/property (the other is not detailed), according to public records. The Times could not find a record of the disposition of the case. He was found not guilty by a jury, Schlaff said.

Saxon later went to the University of Phoenix and Loyola Law School.

His foray into entertainment began at Transactional Marketing Partners (TMP), a direct marketing firm, where he got his start under industry pioneer Earl Greenburg, onetime president of the Home Shopping Network.

By 1994, Saxon founded Insomnia Media Group, a production company, with Bowler, according to court filings. Associates describe the men as tight. The pair crowed that they were the only independent outfit to have offices on the Universal Studios lot.

The fledgling movie producer and doyen in the worlds of direct marketing and infomercials published his second book (with Stein), “The Art of the Shmooze: A Savvy Social Guide for Getting to the Top.”

Using shmooze skills for ‘good, not evil’

The book, which includes photos of Saxon next to O.J. Simpson, Michael Eisner and former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, cautions readers: “Your newfound Shmooze skills are powerful. Please remember to use them for good, not evil.”

After earning credits working on small documentary projects and television shows, Saxon made the leap into feature films.

In 2006 he began bringing in investors for “The Grand,” a mockumentary about a professional poker tournament starring Woody Harrelson and Cheryl Hines.

But the film, released in 2007, would later spark multiple lawsuits by investors that included allegations that Saxon promised 100% of the film’s earnings to each of them, repaying them little or nothing back.

Among them was Zellers, who invested $500,000 in the film.

Saxon’s then-attorney told The Times the movie’s investors had been “paid everything they are entitled to” and that Zellers saw the litigation as “an opportunity to get money back from an investment that didn’t pan out.”

Zellers disputed the claim. He said he was first introduced to Saxon by a mutual friend in 2004. They had their initial meeting at the Ivy in Los Angeles. Zellers, then around 27, had done well in the mortgage industry and Saxon made a strong impression on him.

“Bret’s a charismatic guy; a really good sales guy. He puts on an image, he drives the right cars, he has the Amex Black card,” Zellers told The Times, adding that he was “always throwing out names.”

Zellers first put up $550,000 to fund the 2005 jungle comedy “Blue Sombrero.” Saxon told Zellers it was a “lucrative opportunity.” Robin Williams and Heather Locklear were attached to star while Trent Reznor had signed on to produce the soundtrack, Saxon told him, according to a lawsuit Zellers filed against him in Los Angeles Superior Court in 2011. Further, Saxon maintained that “the only way the both of them would lose money was ‘if the monkeys took over and burned the jungle down.’”

Although Zellers now calls his experience with Saxon “an expensive lesson,” there were early warning signs.

In December 2004, Zellers flew to Costa Rica to visit the “Blue Sombrero” set. Once there, he said he discovered that Williams and the other actors that Saxon had represented as starring in the movie were never contracted, nor was Reznor ever attached to the soundtrack, according to the suit.

When Zellers voiced his concerns to Saxon, he was told his money “remained secure,” and that he would recover his investment “soon,” states the complaint.

By then, however, Zellers was in deep.

In addition to “Blue Sombrero” and “The Grand,” Zellers put up an additional $300,000 for equity stakes in two other Saxon-led projects. One was an investment in IMG Music to produce the soundtrack for a biopic on Tupac Shakur.

Zellers claimed that Saxon told him that he not only had the rights to adapt the film, but the soundtrack would consist of eight never previously released Shakur songs as well as tracks by Jay-Z and Ludacris. But IMG Music never existed, the suit alleged.

Despite his apprehensions, Zellers continued to open his wallet to Saxon, saying he was persuasive.

By 2008, Zellers had laid out about $1.7 million to Saxon and his various entertainment ventures but had not seen a dime. Whenever he asked Saxon where his money was, he was told to “sit tight and have patience and the money would start to flow in,” the lawsuit states.

Schlaff declined to comment on the case.

After years of costly litigation, in 2015 Zellers said he settled his suit with Saxon for a fraction of his losses. He got a lien against Saxon’s house and collected $160,000 last year when it was sold.

“I was naive,” Zellers admited. “I was investing in my first movie. That’s the problem with the movie business. It’s a sexy business and people want to be in it.”

Claims of a ‘Ponzi scheme’

Saxon found others who also wanted their slice of Hollywood.

Between 2007 and 2010, he produced at least nine films. It was a period that eventually launched a tangled legal web giving rise to at least six lawsuits involving Saxon, alleging that he misappropriated or failed to repay more than $7.8 million in investments, loans and fees.

Some backers and former associates claimed that Saxon was operating a “Ponzi scheme,” using money raised for one film to fund another, while promising big returns to investors. Schlaff denied the allegations and said there was no finding that Saxon had ever participated in a Ponzi scheme.

“The thing was with Bret, he just keeps kicking the can down the line. You know, we’re going to make $1 million tomorrow,” says a former associate.

For the record:

2:32 p.m. Nov. 17, 2023This story refers to an orphanage as Palmer House and says it is 150 years old. It is called Palmer Home and is 128 years old.

In one case, a litigant alleged that Saxon misappropriated $750,000 from Palmer House, a 150-year-old orphanage in Mississippi that was earmarked for a film Saxon was making about it in 2010. The production folded just before cameras rolled because the money dried up.

Saxon’s attorney told The Times in 2011 that the money was not returned because it “was spent on pre-production and production costs.”

As investors were left empty-handed, they said Saxon told them the money had been spent on movie-related expenses; he also spun increasingly unbelievable explanations.

Scott Barbour claimed that Saxon owed him over $550,000 for several loans made to him in 2010, according to a fraud lawsuit he filed against Saxon in 2011.

Barbour alleged that after a check Saxon sent him bounced, the producer told him he would be repaid from the $2.5 million in distribution rights Sony Pictures had offered to him for “Con Man,” the biopic he was making about convicted fraudster Barry Minkow.

When Barbour demanded his money, he said that Saxon told him he would sell his Memphis ranch if necessary. He discovered that neither Saxon nor any of his businesses owned it.

After Saxon declared bankruptcy, Barbour eventually stopped pursuing the lawsuit. He died in 2019.

Saxon’s attorney, Schlaff, said Barbour’s allegations were “false.”

Even as investors fought to recover their money, Saxon continued to successfully engage other backers.

In November 2007, the producer announced that Borak Capital Holding, an Egyptian investment fund, was injecting $550 million into Insomnia Media Group.

“It’s an enormous amount to manage. Now we have a big responsibility to manage that and make the money work,” Saxon told the Los Angeles Business Journal, heralding plans for a $70-million war epic to be shot in Egypt, Morocco and Los Angeles.

“They were like ‘we got this $500 million thing with the Egyptians. ‘This is amazing,’” recalled a former colleague. “And then it just never happened.”

In March 2011, Borak sued Saxon, saying the press release was “false” and that the investment fund never agreed to give Insomnia Media any money.

The case was later dismissed at Borak’s request after Saxon’s attorney produced evidence to suggest that Borak was aware of the press release and had suggested phrasing.

Financial troubles mounted and in 2013 Saxon filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy for the third time (he previously filed 1998 in a case that was dismissed and in 1991).

The bankruptcy records disclosed that seven of the business entities under his name, including five companies set up for film projects, had no clients or assets and some had been inactive during periods when Saxon had solicited investors.

The filings showed that he owed over $8 million in liabilities and had less than $200,000 in assets. Saxon did not own a fleet of luxury cars, he drove a loaner.

Schlaff says the bankruptcy came in “the wake of the ruinous flurry of litigation” and notes that “entrepreneurship is sometimes a roller coaster.”

But several plaintiffs who had sued Saxon (including Barbour) believed his bankruptcy filing was a ruse to avoid paying his creditors, as was his divorce from his second wife, Amy Saxon, a former bankruptcy lawyer, who let her license lapse in 2006 after failing to pay her Bar fees.

In 2015, the trustee for Saxon’s bankruptcy sued him, alleging he fraudulently transferred assets, including his interest in the Pacific Palisades home, to his ex-wife. (After the couple defaulted on the mortgage multiple times, the house was sold last year; they currently live in a rental home in the Hollywood Hills, public records and real estate listings show.)

Amy Saxon did not respond to a request for comment.

The bankruptcy trustee reached a settlement with Saxon in 2016. Terms were not disclosed.

A fight with Jessica Simpson

Saxon and his partner, Bowler, soon found themselves embroiled in another lawsuit, this time with former pop singer and reality TV star Jessica Simpson, through her company With You Inc.

In the 2018 complaint, Simpson called Saxon a “professional con man.” She claimed that Saxon and Bowler had befriended Joe Simpson, her father and former manager, in an attempt to “leverage their relationship with him to secure a payday.”

The pair met her father years earlier during a chance encounter at the Grand Havana Cigar Room in Beverly Hills, according to the suit filed in Los Angeles Superior Court.

Saxon represented himself as Grand Havana’s owner and Bowler as an associate; they told Simpson that they had a deal at Universal and could help land movie roles for his daughter. Four years later, they offered to make an introduction for a potential cosmetics brand endorsement in exchange for 15% of the deal. Neither film roles nor the endorsement were secured.

Then, in 2014, when Simpson was negotiating with Sequential Brands Group to acquire a stake in her clothing company, Saxon and Bowler attempted to “insert themselves into the sale,” while concealing their intent to claim a finder’s fee, the suit stated.

Saxon and Bowler asked Joe Simpson to connect them with his daughter’s business manager, David Levin, saying they could introduce him to an executive at Sequential, according to the suit.

In 2015, within weeks of Sequential finalizing the deal to purchase a majority stake in Simpson’s business for nearly $120 million, Saxon turned up in Levin’s office and “demanded a finder’s fee on behalf of Bowler,” saying that he was owed his 10% cut, the suit states. Saxon said he had acted as Bowler’s agent in the deal and that Bowler had an oral agreement with Joe Simpson for making that introduction, according to the suit.

Levin rejected the demand for fees, saying there was no such agreement.

That year, Bowler sued Joe Simpson, claiming he was owed a finder’s fee. Simpson, through her company, countersued.

After the deal closed, Sequential paid Saxon $250,000 for the introduction and he gave a portion to Bowler, the suit said. The cases were settled confidentially in 2018 for undisclosed terms.

Saxon’s attorney declined to comment on the litigation.

While many of Saxon’s investors eventually settled, one of them, Jon Yarbrough, was determined to pursue him in court.

Yarbrough, a wealthy Tennessee entrepreneur who founded Video Gaming Technologies, the manufacturer of slot and other gambling machines, had invested $1.5 million into one of Saxon’s films, “A Fine Step,” about Paso Fino horses, starring Luke Perry.

In a 2010 lawsuit, Yarbrough alleged that Saxon misappropriated funds from the film for his personal benefit. A Tennessee arbitrator found Saxon liable for fraud and breach of contract and ordered him to pay Yarbrough $2.25 million.

But, a year later, Yarbrough’s attorney told The Times that Saxon had not repaid the money. Saxon attempted to get the debt discharged in his bankruptcy, but a judge declined the request, partly based on the findings of fraud, and ordered him to pay nearly $2.4 million in 2016.

Still unable to recover his money, Yarbrough later sued Amy and Bret Saxon, alleging the couple “participated in a sham divorce” to “keep monies away from Bret Saxon’s creditors.” The case was settled in August of 2022.

Saxon has since “apologized” to Yarbrough, Schlaff said, and the men entered into a settlement agreement which Saxon has “honored.”

He called the lawsuits that followed Yarbrough’s complaint a “pile-on” that “succeeded in creating a panic among Mr. Saxon’s business partners and investors.”

In the “Hard Matter” lawsuit, Gridiron alleges that Saxon and Bowler “siphoned money” out of the budget by creating fraudulent loan-out companies for production services that paid Saxon $500,000 and Bowler $450,000.

Powell claimed in the lawsuit that when he investigated the original budget, he found that cast and crew were paid amounts below what was initially stated, among other discrepancies.

In his complaint, Powell alleges he transferred $2.5 million on Oct. 12, 2021, to secure Gibson in the movie. However, in November, days before filming was to start, he contends that Saxon and his partner told him that Gibson had not in fact agreed to star in the film and that they knew he was already committed to another project.

Schlaff called the claims in the lawsuit “frivolous.”

He said that Powell’s entire investment was used toward the film and “confirmed by an audit.” He further noted that Powell, who ran an investment fund for NFL players, had been sanctioned by Georgia regulators in 2018 for misrepresenting his services.

Schlaff supplied transcripts of various emails and text messages as well as screen shots of conversations between Powell, his partner, the film’s director Justin Price and Saxon purporting to show they were aware that Gibson had not committed to the film before Powell invested in it.

Gridiron’s attorney, Joseph Kar, disputes the claim.

“We have clear communications that they used Gibson as a lure and that my client didn’t know he was unavailable,” Kar told The Times. He added that shortly after receiving the money to guarantee Gibson, “they turned around and distributed it to themselves.”

“Hard Matter” remains in post-production and has yet to be released.

Times researchers Scott Wilson contributed to this report

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.