How a kid from El Monte became one of Hollywood’s few Latino executives

- Share via

Scouring his high school class schedule, then-14-year-old Cris Abrego caught his breath.

TV Production.

It was 1986, and the incoming freshman, a self-described TV addict, assumed the course would teach Latino teens like him how to build television sets. After all, this was an era when students in working-class communities, including those at El Monte’s Mountain View High School, were encouraged to take auto or wood shop to prepare for a blue-collar life.

“When I found that it was actually to make television, I was blown away,” Abrego said.

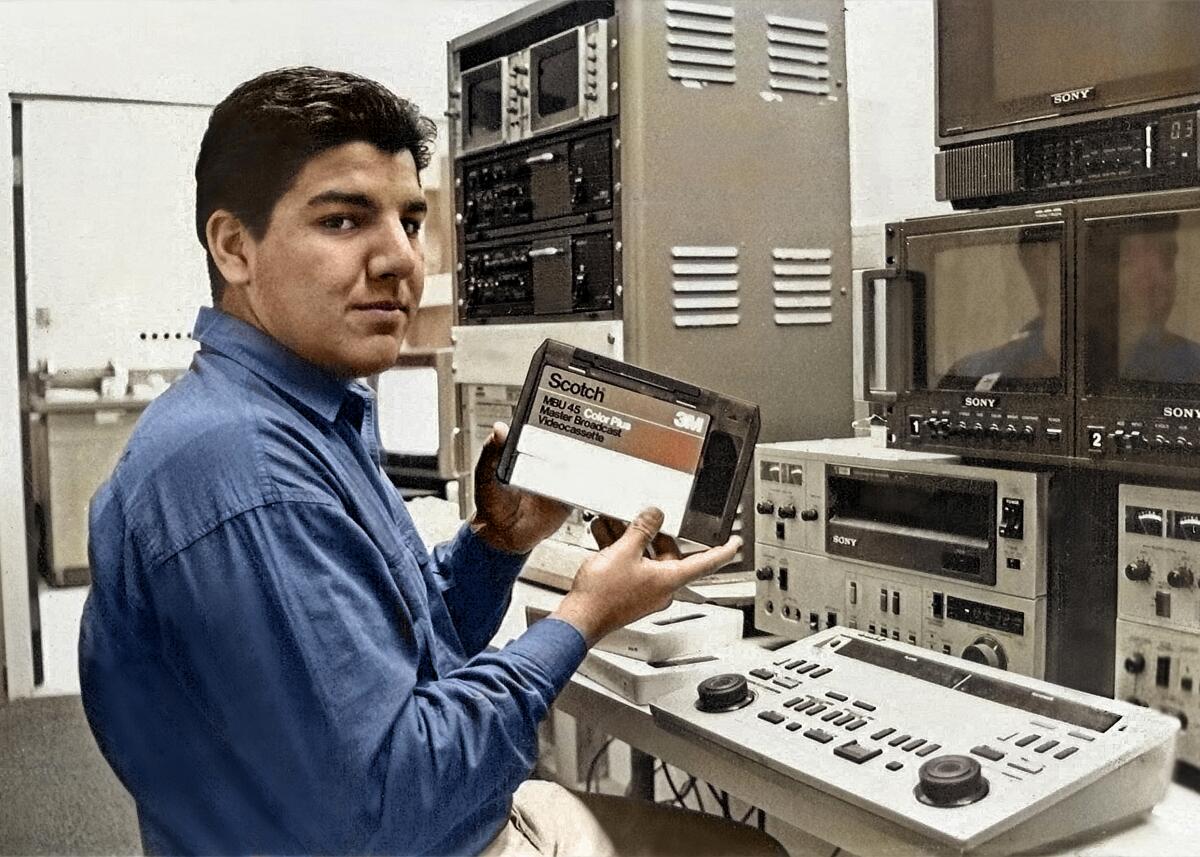

That class would prove instrumental in shaping ambitions that would take him beyond El Monte. By his junior year, Abrego was lugging around a bulky TV camera, interviewing fellow athletes, cheerleaders and the principal for a student-produced show, “What’s Up,” which borrowed heavily from “The Arsenio Hall Show” — albeit with less glitz.

Today, Abrego is one of Hollywood’s few high-ranking Latino executives, overseeing U.S. and Latin American operations for reality TV juggernaut Banijay. The French-owned company owns rights to such shows as “Survivor,” “Big Brother” and “MasterChef.”

Still, the 50-year-old Abrego often has felt out of place in a business that has long embraced white executives, many from privileged backgrounds. It bothers him that Hollywood has been slow to recognize the effects of its insular attitudes, which can seep into programming consumed by millions.

Latinos, in particular, have been shut out of entertainment’s upper ranks even as the industry has pledged to do better. Rising concerns about the glaring disparity have reached boardrooms and Congress. Last fall, a Government Accountability Office report found that Latinos — 18% of the U.S. workforce and nearly 40% of California’s — comprise only 4% of media executives.

Abrego has been trying to pry open the industry. He serves as chairman of the Television Academy’s foundation, its charitable arm, where he and other executives created an internship program to support young talent from L.A.’s disadvantaged communities.

“I’ve seen how hard it is to get into this business,” Abrego said. He’s also familiar with assumptions made about Latinos. “I’ve had enough keys thrown at me while standing by a valet stand.”

Seeds of change were planted during el movimiento.

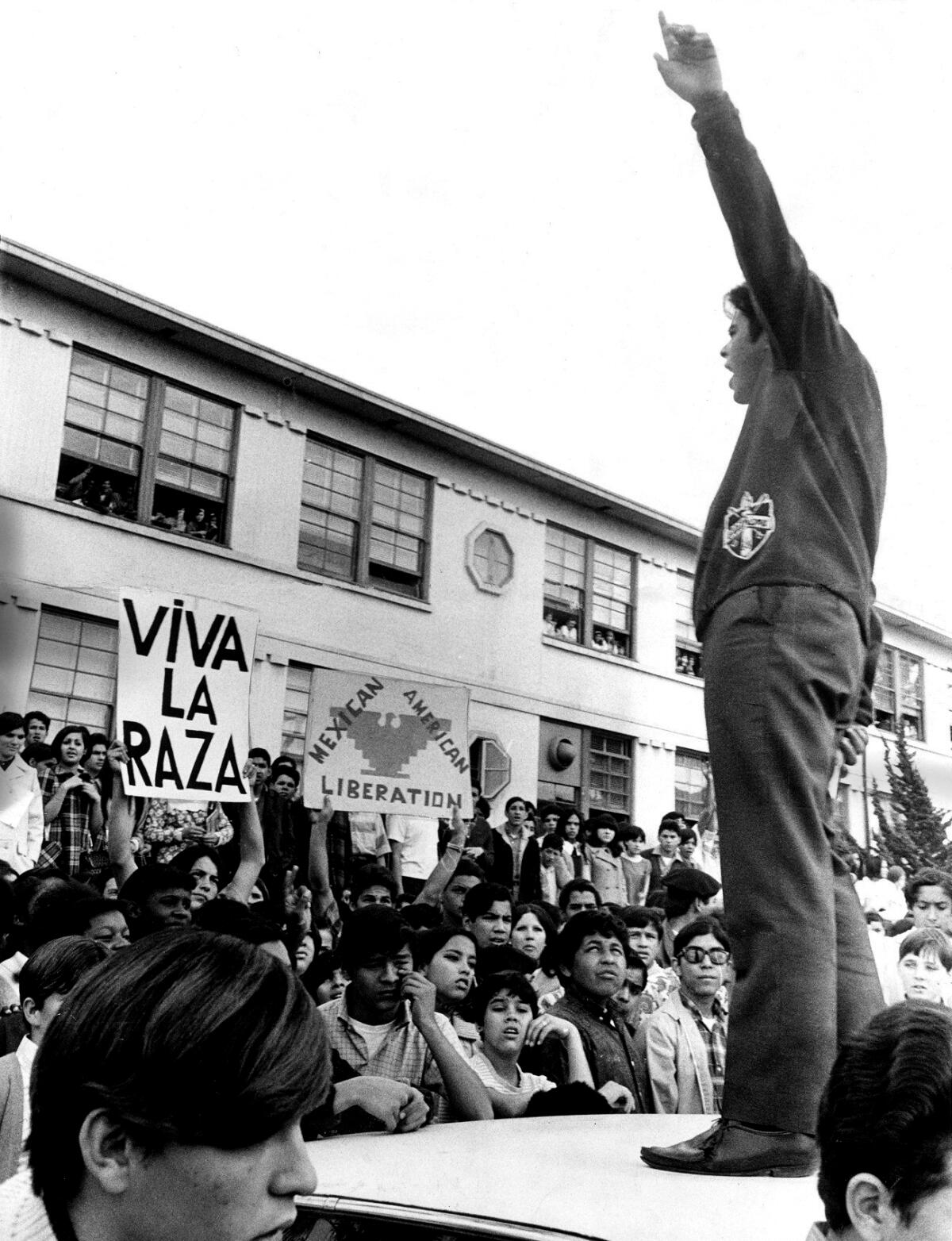

Young Latinos in the 1960s were inspired by the Chicano movement, including Florentina Carrasco Abrego, the sixth of nine children born in Mexico to a homemaker and seasonal farm laborer who “worked the fields here in California,” she said. She moved to L.A. at the age of 13 in 1963, the year her mother died, leaving her older sisters in Boyle Heights to care for Tina and her younger siblings.

Tina Abrego attended Lincoln High School and was among the estimated 22,000 high school students who walked out of their classrooms in March 1968 to protest inequalities in the Los Angeles Unified School District. “We just wanted a better education,” she said. “I’d never heard the word ‘college’ before the walkouts.”

Determined to go, she enrolled at Cal State Long Beach. There, she met Silas H. Abrego.

The son of grape pickers, he was raised in Pomona and after high school was a paratrooper in the Army’s 173rd Airborne Brigade, stationed in Japan. He completed his tour just weeks before his unit mobilized for Vietnam and attended a vocational school. “I was going to be a machinist,” he said. But a teacher who tutored him in math steered Sy Abrego toward college.

At the time, there were so few Latinos at Cal State Long Beach that “I was often mistaken for being an Arab,” Sy Abrego said. He was politically active, serving as president of the campus United Mexican American Students.

“On weekends, we would get our signs and go to the Safeway markets and boycott the lettuce and grapes because of the farmworkers’ conditions,” Tina Abrego said. “Then we got into protesting the Vietnam War. We just wanted to help make change.”

They married in 1969 and had a son, Esteban. Their second son, Cristóbal, arrived in 1972, and the following year, they bought a modest home in El Monte, 12 miles east of downtown Los Angeles. They could afford it, just barely, because Sy Abrego had been hired as the first director of USC’s El Centro Chicano (Chicano Student Center).

“My dad was the only guy in the neighborhood who wore a tie to work,” Cris Abrego said.

Education was stressed in the home. Sy Abrego earned his master’s, then his doctorate in education. He joined Cal State Fullerton, where he spent 27 years, retiring in 2012 as acting vice president for student affairs. Former Gov. Jerry Brown appointed him to the Cal State Board of Trustees and he helped oversee the 23-campus system until last year.

For decades, Sy Abrego gave speeches to students and community groups. He spent hours practicing.

“Cris was always the one who had to listen to the speeches,” said Tina Abrego, noting that she would be busy with housework or her studies. (She returned to college, earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and became a school administrator in Pomona.)

“Cris grew up learning about the inequities that minorities face,” Tina Abrego said. “Cris grew up hearing our stories.”

He remembers his family’s boycott of grapes and its embrace of civil rights.

“We would talk about things that were unjust,” Abrego said. “We would talk about creating equity.”

Family life had a certain rhythm: work, school, sports — and TV.

“As a youngster, he used to sit with me all the time and watch TV,” Sy Abrego said. “He wouldn’t miss any of those ‘Kung Fu’ episodes or old comedy shows.”

“Hill Street Blues,” the ‘80s police procedural, was a favorite, as were repeats of Norman Lear’s “Sanford and Son” and “Good Times.”

“It was the first time that I saw people of color on the screen,” Cris Abrego said. “Those shows felt more real to me.”

Sports was his other love.

In high school, Abrego became an All-American wrestler known for quickly toppling opponents. To maintain his 175-pound weight, Abrego would run along the San Gabriel River wearing a black plastic trash bag.

He’s long been driven by a competitive streak that served him on the wrestling mat and in life. “I believe that’s where he really got used to relying on himself to power through adversity and strive for the very top,” said former business partner Mark Cronin.

Abrego attended Cal State Fullerton on a wrestling scholarship. During his freshman year, he returned to El Monte and one afternoon was riding a motorcycle with a friend, Carlos Hernandez Jr., on the back. Traveling about 50 miles per hour, Abrego made a turn, hit a curb and lost control. Both he and Hernandez went flying.

Hernandez slammed into a concrete light pole and died. When Abrego regained consciousness, he was handcuffed to a hospital bed. He was charged with vehicular manslaughter, a felony.

A jury convicted him the following year, but the judge sentenced him for a misdemeanor. Abrego spent time with Caltrans crews and prisoners, cleaning trash along freeways for community service.

But the pain cut deep. He sports a tattoo above his left bicep — a sketch of Hernandez and the words “Memories of El Monte.”

After graduating from Cal State Fullerton, Abrego was ready to break into entertainment.

But Hollywood wasn’t interested.

Seemingly countless trips to L.A. ended in rejection. “It was hard to fit in because I didn’t have shared experiences with a majority of people in this business,” Abrego said. “I didn’t go to a school on the East Coast. I didn’t go to Europe for a summer.”

Finally, he answered an ad for a part-time sports editor at a Palm Springs-area TV station, KMIR. The interview went well, and the assignment editor suggested Abrego stick around to meet the sports anchor. But the anchor called in sick. Now the station had a question for Abrego: Could he compile sports clips for the newscast?

He gamely pitched in, and afterward lingered in the lobby to watch the newscast.

“When my sports highlights came on over the TV ... chills,” Abrego recalled. “I couldn’t believe it was going out to people’s homes. That cemented it, I wanted to be in this business.”

He reported for work the next day and spent 14 months producing live TV in the desert, moving up to become a director. But he was getting married, his soon-to-be (and now) wife had a job in L.A. and he desperately wanted to make it in Hollywood.

He still struggled to get interviews. But one of his mother’s friends had a daughter who worked in TV and she recommended Abrego to a friend who was putting together a game show for Fox. The interview went poorly, but undeterred Abrego made small talk about his big dreams. He was hired as a production assistant.

The show, “Big Deal,” lasted just six episodes. But Abrego finally had a Hollywood credit — and newfound industry friends. One recommended him for a job at Bunim/Murray Productions, the powerhouse reality TV producers of MTV’s “The Real World” and “Road Rules.”

Abrego started there as a “logger,” taking note of video scenes and time codes. He loved the fast-paced culture and relished lunchtime pitch sessions that Mary-Ellis Bunim and Jonathan Murray held in the atrium of their Van Nuys building.

Over Panda Express takeout, Abrego said, “I learned to develop shows and understand the process.”

After a couple of years, Abrego grew restless and, wanting to become an executive producer, launched his own company in 2001 with a fellow producer, Rick Telles. “Survivor” had become a smash hit for CBS, and networks were hungry for reality TV.

An agent introduced Abrego and Telles to Cronin, and they pitched “The Surreal Life” to the WB network about fading TV stars living together in Glen Campbell’s former Hollywood Hills mansion. Network executives suggested they work with established producers.

They approached Bunim and Murray — but they couldn’t come to terms.

“We took umbrage with the fact that the show felt so derivative of ‘The Real World,’” Murray said. “A boneheaded move on our part turned out great for Cris. It really positioned him to move up in the industry.”

Because Abrego and Cronin owned the show (rare for a reality show), they were able to move it to VH1 when it finished its WB run. Around this time, Abrego had a falling out with Telles, who launched an eight-year legal battle over show rights and profits. Telles won an $8-million arbitration award.

Business was booming. “The Surreal Life” reenergized VH1, which ordered other Abrego- and Cronin-produced “celebreality” shows. The Times featured Abrego and Cronin in a story headlined “The kings of dubious TV.”

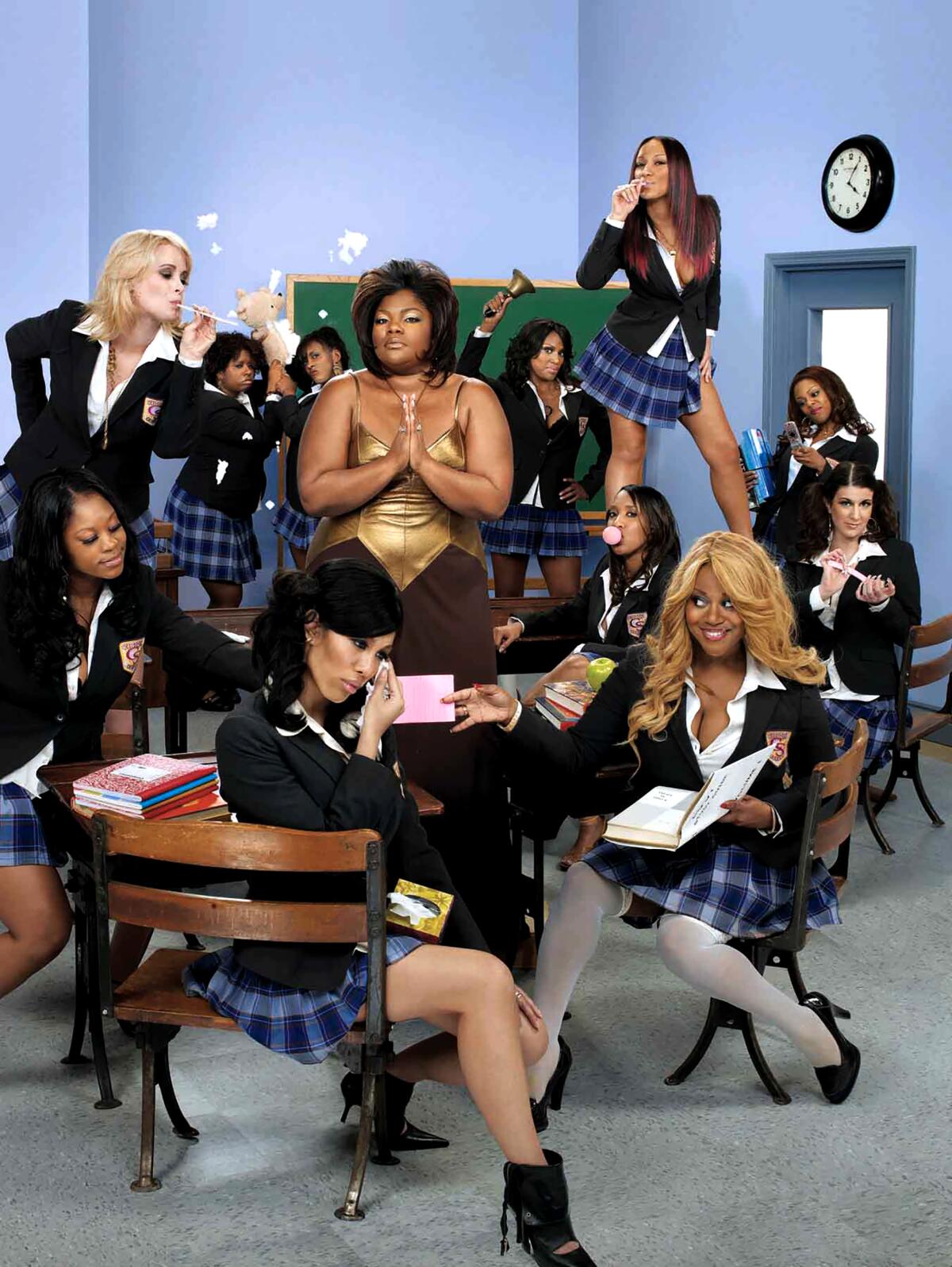

One of their shows, “Charm School,” centered on unsophisticated young women taking lessons on style and class. The show’s first-season star was the outspoken comedian Mo’Nique. On the first day of production, she called a time out.

“The assistant director came running and said: ‘Mo’Nique has asked us to gather the entire production crew in front of her,’” Abrego recalled. “She wanted to see how many people of color were working on the production. ... They’re talking to me, this brown kid from El Monte.”

Abrego was chagrined that the show, featuring a diverse cast, was being produced by a nearly all-white crew.

“It hit me like a friggin’ ton of bricks,” Abrego said. “Her point was that representation matters.”

Within a few years, Abrego found a way to apply the principles his parents long talked about — opportunity and equality — to his own world of entertainment.

Abrego and Cronin’s success attracted interest from Dutch reality TV giant Endemol. In 2008, Endemol USA bought a majority stake in their company, 51 Minds Entertainment. The pair remained another six years as managers, and Abrego segued into the corporate suites.

In 2013, Abrego was offered the job as co-CEO of Endemol North America. He was reluctant: The desk job paid less than producing — and he acknowledges being a bit intimidated because he didn’t have an Ivy League education or an MBA.

“But my dad looked at me and said: ‘Mijo, son, you have a responsibility to take the CEO position,’” Abrego said. “He said: ‘Those three letters will become more important to other people, other Latinos, than they will to you.’”

His father’s words weighed heavy.

Few Latinos have made it to the top of major TV networks and studios. Latino executives often have been steered into Spanish-language television.

“That’s great, but that shouldn’t be the only place where you have Latino executives,” said Ana-Christina Ramón, director of research and civic engagement for UCLA’s social sciences division and co-author of UCLA’s influential Hollywood Diversity Report.

“The U.S. Latinx consumer is very much into watching mainstream television, which is English-language programming,” she said. “It’s not enough to just have Latinx actors on screen, you have to have executives that really understand the community.”

Now, Abrego lives in Sherman Oaks with his wife and three children. As Banijay’s chairman of the Americas, he oversees more than half a dozen production companies, including Endemol Shine North America and Bunim/Murray Productions — where he got his start. He’s determined to empower Latinos and he’s also aggressively championed his company’s Spanish-language business, selling its shows to Telemundo, Univision and Netflix.

“I realized that from where I sit, is that those three little letters in my title — CEO — gave me the access to do more,” Abrego said.

Four years ago, his old boss and now underling Murray suggested creating a training program to provide substantial opportunities for young people of color who can’t afford to take an unpaid internship or a low-paying assistant job — the typical routes to a Hollywood career.

“People from modest income families couldn’t afford to do that,” Murray said.

Murray and Abrego raised more than $1 million for an endowment to provide paid internships as part of the TV Academy Foundation’s Diversity and Inclusion Unscripted Internship Program. Beyond the foundation, Abrego has been working on incubator projects and other industry hiring initiatives.

Such efforts come nearly a decade after Abrego launched his own self-funded initiative to help student athletes from Mountain View High go to college. His mom, Tina, helped administer the program, which has provided tuition money and other support, such as computers, to nearly two dozen students since 2013. The program is called the Carlos Hernandez Jr. Memorial Scholarship.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.