Q&A: ‘PBS NewsHour’ anchor Judy Woodruff wants substance over style in presidential debate

- Share via

The 2020 Democratic presidential primary debate roadshow is coming to Los Angeles on Thursday and “PBS NewsHour” anchor and managing editor Judy Woodruff — a veteran journalist who has covered the last 11 presidential campaigns — will be at the moderators’ table when seven candidates take the stage at Loyola Marymount University.

The “NewsHour” is teaming with Politico for the event that begins at 5 p.m. Pacific and will be seen on PBS TV stations nationwide, and simulcast on CNN and its digital platforms. The debate will also be streamed on “PBS NewsHour’s” Facebook, YouTube and Twitter pages and broadcast on NPR stations. Woodruff, who will be co-moderating with Politico’s Tim Alberta and “News Hour” correspondents Yamiche Alcindor and Amna Nawaz, recently shared some thoughts about presidential debates past and present.

Does the timing of this primary debate — the sixth since June — make it any more challenging? Based on the TV ratings, interest in this field of candidates has subsided from those first few debates when there was a lot of curiosity. And we’re still seven weeks away from the Iowa caucus. So do you have to think about how to make this a pivotal event?

We have seven candidates, which would be the smallest field on a stage for these Democratic National Committee sponsored debates. So in a way that gives us more opportunity to ask direct questions to candidates, to ask the candidates to engage, hopefully to explore where there’s any daylight among them, and to get to some issues that maybe we haven’t gotten to before.

So what is the preparation process like? Do you do a mock debate where production assistants and other staffers play the different candidates?

Our team is working very closely with Politico in terms of research, in terms of thinking about questions and what’s the best way to phrase a question. We’ll do mock debates where we try questions and have producers, production assistants and folks like that who’ve been part of this process. I think that’s what everybody does now.

Being that it’s PBS and there’s no commercial incentive here, is there also an opportunity to maybe structure it differently to make the debate more substantive?

You just put your finger on it — substance. Our main goal is to try to put ourselves in the shoes of the American voters and [ask] what are they interested in? What are they looking for? What do they want to know from these candidates? How do they better understand them? Whether it’s their positions on the issues, or what about their character, or how they make decisions, what kind of leader would they be — all those things come into play. In terms of format, we’re not looking to do something wild and crazy here. We’re looking to keep the focus on the candidates and to let them talk about the most important issues.

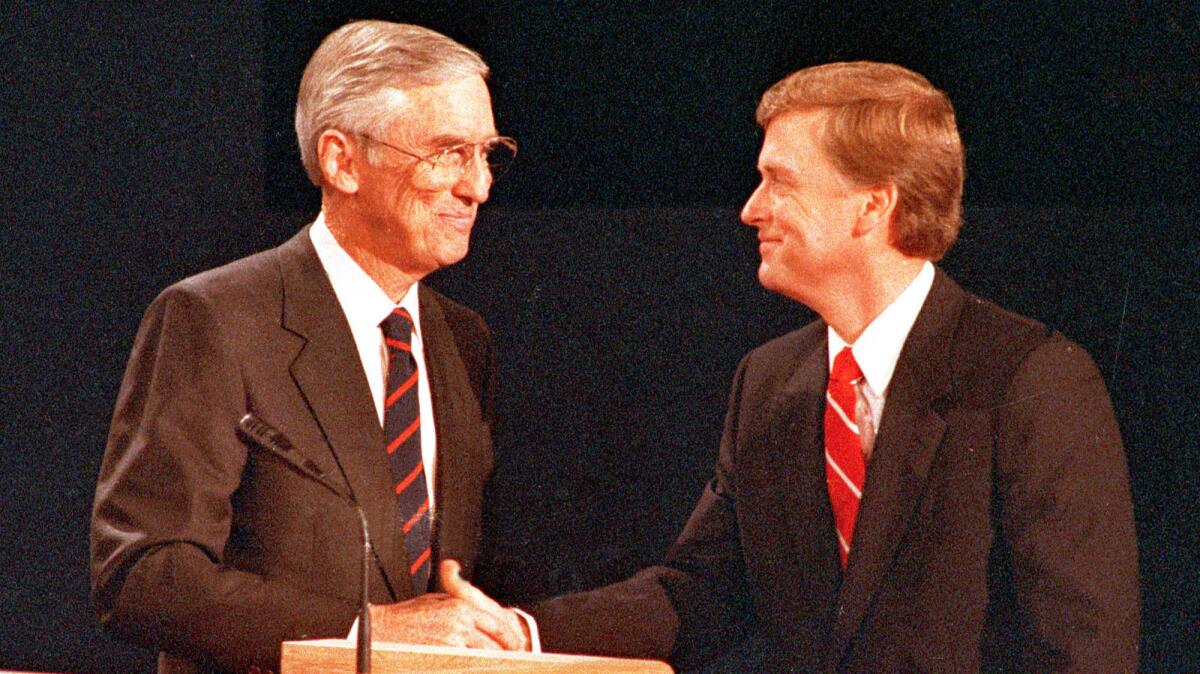

You’re a veteran of presidential debates. You did the general election debate in 1988 between the vice presidential candidates, when Lloyd Bentsen told George H.W. Bush’s youthful running mate, Dan Quayle, “I knew Jack Kennedy. Jack Kennedy was a friend of mine. You’re no Jack Kennedy.”

That’s right, that’s what everybody remembers about that debate. The room exploded when Bentsen said that. And it’s a reminder about what debates are, because everybody listened to that and they thought, “Oh, boy, that’s the end for Dan Quayle.” And then, of course, he and Bush went on to win the election.

You’ll have three female moderators at your debate. And we had four female moderators at the last Democratic primary debate on MSNBC. You came up in the 1970s when there were few female correspondents covering Washington for the networks. How does it feel to see this kind of representation now?

I think it’s exciting. I think it’s appropriate. Four years ago, Gwen Ifill and I moderated the one of the primary debates between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders in February of 2016. So it started to improve years ago, but I think we’re now at the point where when you don’t have a diverse group of moderators, it looks out-of-place. Because journalists have become more conscious of how important it is to look like the country. We may be late in journalism, but we’ve finally come around. To have a lineup of moderators that is all cookie-cutter, lookalike — that just wouldn’t happen.

Is that a change that you ever imagined when you were blazing the trail a few decades back?

Not even close. When I started out all the major political reporters, the main political reporters certainly for print ... the Johnny Apples, and the David Broders and on and on — they were men. And there were certainly a few women coming up, but they were often not given permanent slots. I think the networks were a little ahead of print in including women in [covering] these events. But to be where we are today, — there’s just no way I would’ve imagined. And you could argue, well, I should’ve imagined it, and it should’ve been a whole lot sooner than it was.

The news cycle is nonstop and chaotic these days. Are you seeing any dividend at “PBS NewsHour” from sticking with its sober, steady approach to the news because there are fewer places doing it that way on TV?

Absolutely. I hear every single day from our viewers and our online followers that they appreciate what we’re doing, They are desperately looking, many of them say, for facts, for straight reporting. And I’ve never heard the kind of response that we’re getting today, which is incredible. I mean, on the one hand it’s heartening; on the other hand, it says something about where we are as a country and where journalism is today, that people are coming to you and saying, “I don’t know where to turn for information, for news that I can believe in. And I’m so grateful that you are there.” People stop me at the airport or at the coffee shop. People are saying to us, “Thank goodness for what you guys are doing. You’re doing the journalism that matters today.” Honestly I’ve never seen the kind of affirmation that we’re getting today.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.