How a bestselling Irish writer changed the way we read (and publish) short fiction

- Share via

On the Shelf

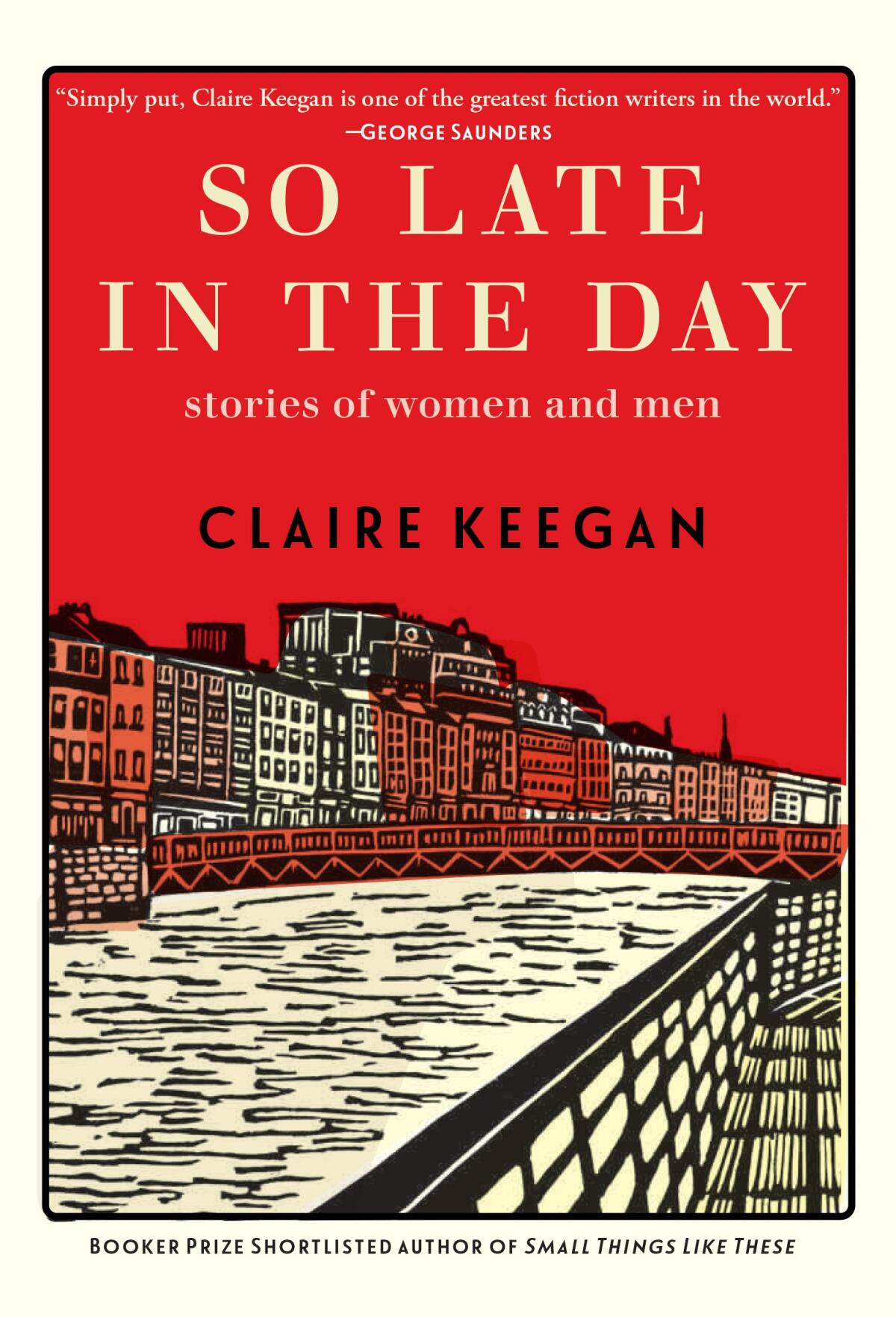

So Late in the Day: Stories of Women and Men

By Claire Keegan

Grove: 128 pages, $20

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Consider, for a moment, the unforgiving nature of short fiction. Many highly esteemed novels contain stretches that stumble, lumber and digress, with such “fat” either pardoned in the larger context of the meal or praised as authorial swagger. The pleasures of poetry, meanwhile, are so rooted in the abstract and ephemeral that not getting the point can be the point. But the short story or novella comes to life — or fails to — within a margin of error more familiar to neurosurgeons than to writers of fiction. One shaky moment and the operation can flatline.

The Irish writer Claire Keegan has over 25 years proven herself to possess an astonishingly steady hand, her taut stories and novellas commanding not just critical fawning and prestigious prizes but, lately, sales to rival even bestselling genre fiction.

Irish author Claire Keegan is one of those U.S. ‘discoveries’ who have been known back home for years. With ‘Foster,’ she earns that acclaim and more.

Keegan began her career with two revered short-story collections published nearly a decade apart, “Antarctica” (1999) and “Walk the Blue Fields” (2008). In conventional narratives of writerly ascents, these would be followed up by the sweeping novel that invariably gets praised for “fulfilling the promise” of the early stories. But in the years since, Keegan has opted for a path more befitting an author whose tales often mesmerize by thwarting expectations. Paring down even further in style and output, she has entered a rarefied stratum — and defied publishing economies of scale — by releasing her new stories in slim, standalone volumes that feel like sly acts of rebellion: declarations that a finely etched story deserves the same stage as a sprawling novel.

“Foster,” published in the U.K. in 2010, made her one of the most celebrated writers in Ireland, where the 89-page tale of a young girl taken in by a childless family has become a staple of the public school curriculum. Eleven years later came “Small Things Like These,” her haunting account of a coal merchant who discovers a girl imprisoned in the shed of a Catholic convent. That work earned her comparisons to Anton Chekhov, became an international bestseller, was optioned for a film adaptation (set to star Cillian Murphy) and landed on the Booker Prize shortlist. At 114 pages, it was the shortest work ever to receive that honor. Following its success, “Foster” was issued last year by her American publisher.

The arrival of Keegan’s newest book, “So Late in the Day,” offers further confirmation of her spellbinding powers: the unpretentious language that feels forged in a hearth, the evocation of a pastoral but repressive Ireland, the characters whose predicaments remain lodged in your consciousness far longer than the epic battles of 1,000-page sagas.

The title story concerns a Dublin man named Cathal who, on the brink of middle age, has been undone by his own misogyny. We spend one fateful day with him, meeting him first in his office as he stares out the window — the kind of seemingly humdrum scene that Keegan is expert at infusing with ambient tension. The last two lines of the story’s first paragraph display the cunning with which she can light a fuse: “Down on the lawns, some people were out sunbathing and there were children, and beds plump with flowers; so much of life carrying smoothly on, despite the tangle of human upsets and the knowledge of how everything must end.”

Christopher Nolan made ‘Oppenheimer’ lightning-fast, but the story of writing and adapting the source book, ‘American Prometheus,’ is a half-century epic.

To outline the plot any further would be a disservice, as Keegan has structured the tale so that a reader only grasps the full scope of its narrative in the very last sentence. In this it joins its most recent predecessors, pieces that derive their power from a suspenseful atmosphere and pacing.

In “Foster” Keegan achieved this through a first-person child narrator, with the reader aware of complexities the protagonist has yet to grasp; in “So Late in the Day,” as in “Small Things Like These,” the effect is rendered through a close, almost claustrophobic third-person that keeps the reader partially in the dark and increasingly on edge. Something is very wrong or going wrong … but what?

You read Keegan with eagerness and dread, knowing that what’s in store will leave a permanent mark on her characters and readers. You also savor her work in much the way you might stare at an ancient marble sculpture, equally transfixed by what’s on the page and what must have been cut away to create it.

“So Late in the Day,” published in Britain and Europe as a 47-page hardcover, is supplemented in the U.S. edition by two works from her earlier collections, making the book something of a retrospective. The second story, “The Long and Painful Death,” chronicles a female writer whose residency at the home of Heinrich Böll is soured by the arrival of a male academic. And Keegan sets up the arc of the final piece, “Antarctica,” in its first two sentences: “Every time the happily married woman went away, she wondered how it would feel to sleep with another man. That weekend she was determined to find out.” Over 29 harrowing pages, Keegan tightens a noose around what both her protagonist and reader are anticipating.

Short books are great, but I prefer the those loose, baggy monsters that you wish would never end.

What is perhaps most astonishing in reading the three stories together is that they don’t showcase Keegan’s maturation as a writer over more than two decades so much as remind you of how long she has simply been a master of the craft.

A critic has the unfortunate task of sniffing for bones to pick. If there are any in “So Late in the Day,” they are not in Keegan’s stories but on the cover of the U.S. edition. The book is presented with a subtitle “stories of women and men,” which, however apt thematically, feels cloyingly expository for a writer who embraces ambiguity and whose work feels almost anti-didactic, propelled by a trust in a reader to draw her own conclusions.

It’s true that Keegan’s stories can be read as biopsies that expose larger cancers — the abuses of the Catholic Church in “Small Things Like These” or, in the triptych composing “So Late in the Day,” an indictment of patriarchal culture. But you read Keegan, and are hypnotized by her, for the way she tends to her characters: as messy people rather than tidy concepts, brought to life in stories governed by an innate recognition that everything that rises to the level of the universal begins at the personal.

Amsden is a writer based in Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.