A ‘canceled’ author falls for a cringe icon in ‘The Book of Ayn’ (Rand, of course)

- Share via

Review

The Book of Ayn

By Lexi Freiman

Catapult: 240 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

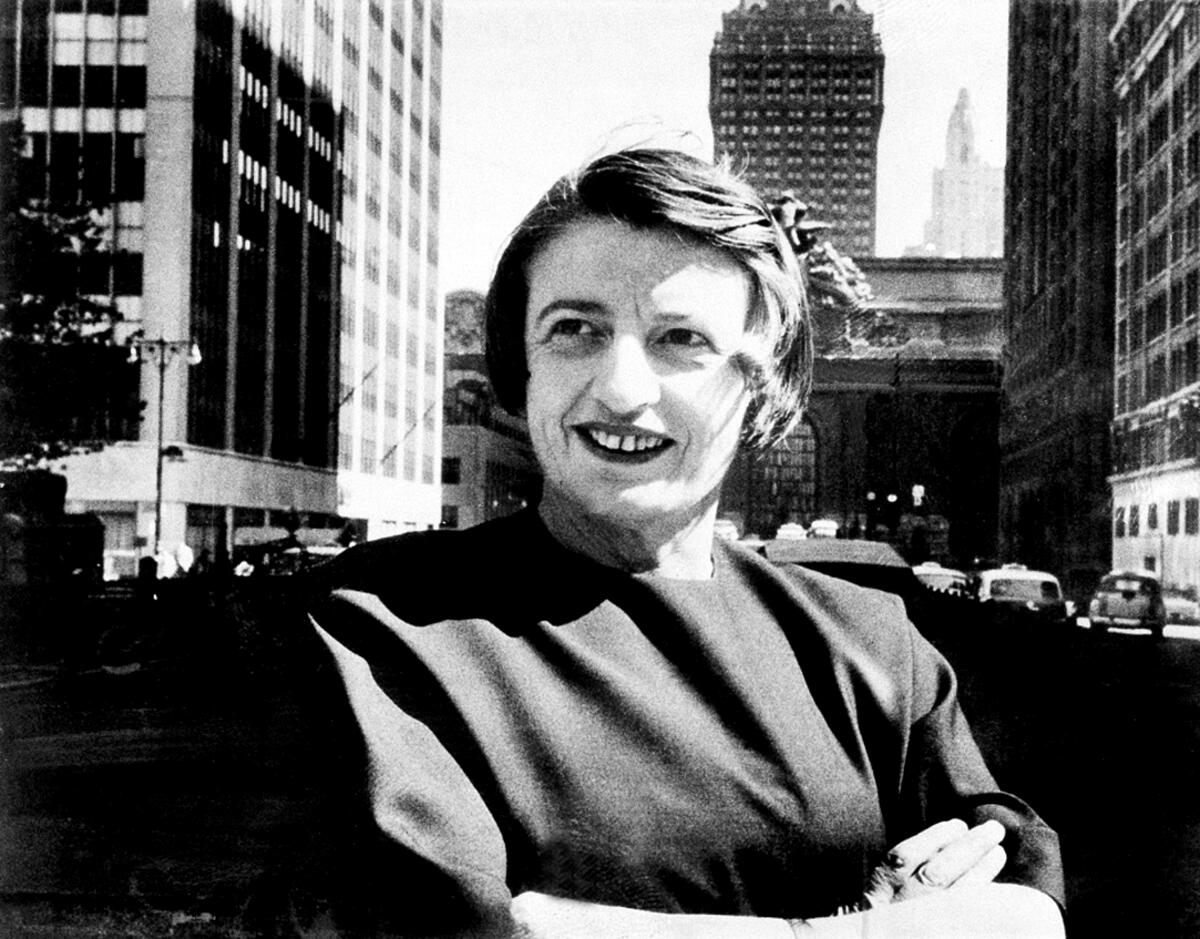

To answer your question: Yes, Lexi Freiman’s “The Book of Ayn” is about Ayn Rand, the bug-eyed author of “Atlas Shrugged” and “The Fountainhead.” The founder of Objectivism, which extols rationalism and selfishness above all else, and whose disciples include Peter Thiel, former Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan and many young men averse to moral complexity.

Putting Rand in the title of one’s satirical novel feels like a dare, or at least — in a hyper-polarized time — a provocation. The good news is Freiman has written one of the funniest and unruliest novels in ages. It shakes you by the shoulders until you laugh, vomit or both.

Rand isn’t a character but the object of undue idolatry for Anna, a 39-year-old writer whose own “satire of the opioid epidemic” has just been called “classist” by the New York Times. (One might divine the author’s inspiration from the Grey Lady’s review of her debut, “Inappropriation.”) In short, Anna has been canceled. She also worries she’s a narcissist. And now her career, finances and identity are all in jeopardy.

In Julius Taranto’s debut novel, ‘How I Won a Nobel Prize,’ a physicist follows her mentor to a university staffed with canceled luminaries. High jinks ensue

Freiman knows being canceled just means you’re invited to different parties. Anna attends the Upper East Side luncheon “of a conservative socialite rumored to be hiding an Islamophobic Muslim authoress with a fatwa from the liberal media” and later heads off to “a ‘dissident soiree’ at the West Village townhouse of a famously contrarian female columnist.” But Anna’s skepticism and humor make her a pariah among the pariahs.

Primed for religious conversion — or a philosophical life raft of any kind — she chances upon a tour group visiting Rand’s New York haunts. Drawn to their certainty, Anna finds solace in one of the 20th century’s most famous contrarians: “Her ideas had the uncanny chime of paradox. The dizzy zing of the counterintuitive. She wasn’t funny but I enjoyed her thoughts like I enjoyed jokes. Like anything audacious; true because it’s wrong.”

Anna’s friends recoil at her new infatuation, but she doesn’t mind. Rand serves a need she can’t get from living people. Here, Freiman scratches at the difference between knowing and knowingness, and how our blind spots can subsume our personality. The Australian private school teenagers of “Inappropriation” misread Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto,” confusing the feminist scholar’s post-human reshaping of animal and machine for a trendy costume; Anna’s identification with Rand is similarly all out of proportion and sense. This makes for page after page of high comedy. The exuberant first-person “I” almost demands to be printed at a larger font size than the rest.

The novel turns picaresque when Anna is whisked away to Hollywood on the thin pretense of an Ayn Rand television show. Maybe a miniseries. Perhaps something animated? (She funds her trip with a loan from her father on the condition she visit a fertility doctor, who then informs her she’s perimenopausal.) Anna unwittingly moves into a hype house of content creators for a platform she thinks is called Jizz. Easy parody and scatological humor follow. Think Ruben Östlund’s “Triangle of Sadness.”

Ayn Rand’s ‘Atlas Shrugged’: What the critics had to say in 1957

After insulting her way to yet another exile, Anna decamps for a commune on the Greek island of Lesbos. She’s promised ego death and the teachings of a deceased guru who once owned 350 Harley-Davidsons: “As much as I wanted to destroy my sense of self, I was excited to enter a world built on the teachings of a truly spectacular pariah.”

She’s joined by her friend Vivian, whose politics are consistent only insofar as they prove the horseshoe theory of extremist left-right convergence. In short order, Rand is discarded for a blend of movement therapy, New Age sentiment and ahistoricism. To her own surprise, Anna settles in nicely, beginning an affair with a Tom Cruise-obsessed Polish teenager who high-fives mid-coitus. (Freiman excels at writing cishet intercourse.)

While the novel hums with energy in its last third, the passage of time wobbles; what feels like days turns out to be several weeks. Anna’s narrative drift takes her to Athens, leading to an ending some may find perfectly natural and others dissatisfying. But “The Book of Ayn” is rife with dissatisfactions — to its credit — and with self-aware jokes and serious questions about self-awareness. Also: serious questions about jokes.

The setting recalls Don DeLillo’s novel “The Names,” but the true antecedent is Philip Roth’s “Sabbath’s Theater,” which Freiman name-checks. Roth’s masterpiece also ruminates on the submerged grief for a deceased brother and the true freedom of anti-Puritan licentiousness. (It also takes pot-shots at a New York Times critic.)

Blake Bailey’s biography of Roth has been criticized for channeling a selfish misogynist. This critic believes he knew exactly what he was up to.

Ultimately, though, the author torques her contrarianism past trolling, past knee-jerk philosophizing and past satire, alchemizing a critique of literary culture in all its ideological waywardness. After all, when everyone you encounter is performing themselves, skepticism becomes a rare and essential quality. It might also provide a path toward genuine physical, emotional and literary connection. (High-five.)

Chapman is the author of the novels “The Audacity,” out in April 2024, and “Riots I Have Known.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.