Californian author Ed Park’s wildly ambitious novel of alt-history Korea

- Share via

Review

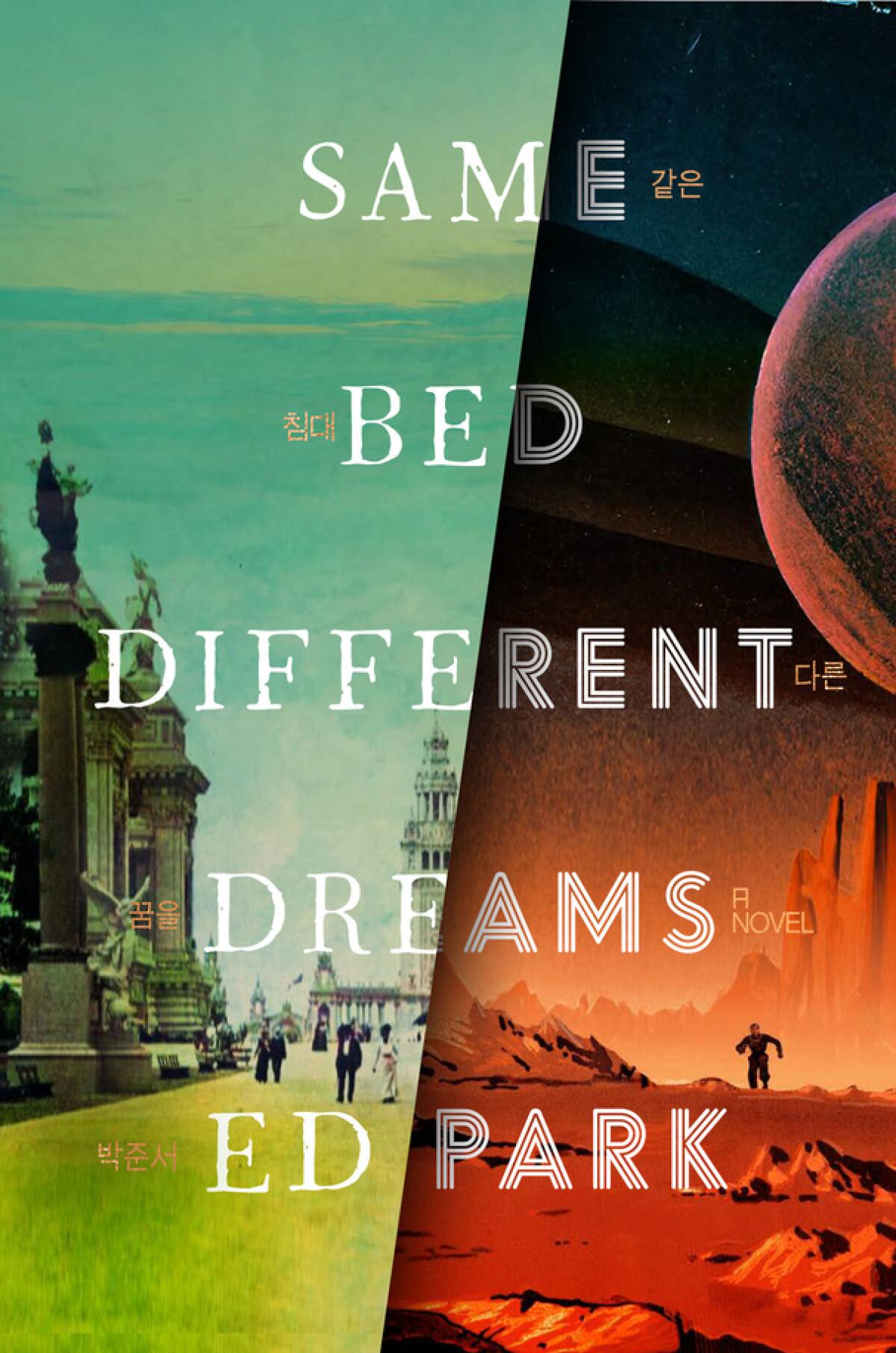

Same Bed Different Dreams

By Ed Park

Random House: 544 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Ed Park’s first novel, “Personal Days,” took place in the offices of an unnamed company and satirized the hollow subterfuge of corporate-speak. Divided into three sections that each employ a different narrative technique, Park’s 2008 debut teemed with the business vernacular of emails, memos and meetings, and the sheer variety of voices and forms results in a dual portrait of the company’s employees and its collective ethos.

Park’s follow-up, “Same Bed Different Dreams,” arrives a full decade and a half later, with all the heft, complexity and ambition such a lengthy interim suggests. The author has greatly expanded his literary scope and complicated his narrative technique, though certain fundamentals remain.

Rather than a portrait of a company, the entity at the center of Park’s new novel is a country, and this time it’s not an anonymous representative of a common culture but a real place: Korea. His specific focus is its resistance to Japanese rule from the early 20th century until the end of World War II, when Japan relinquished control and Korea split into North and South.

In E. J. Koh’s new novel, ‘The Liberators,’ a family flees repression in South Korea for California, but finds the trauma of history is harder to escape.

Using the real history of the Korean Provisional Government (KPG) as his starting point, Park weaves into the factual accounts alternate versions of Korea’s fate, in which the KPG’s reach and membership extend well beyond national borders. Numerous people who had nothing to do with the group, some of whom died before the KPG’s inception in 1919, are given honorary membership, as the KPG is “more a state of mind than an actual governing body,” resulting in an ever-growing mosaic of disparate figures including Marilyn Monroe and Jesus Christ.

In addition to its history, Park also explores the various ways other cultures depicted Korea — from George Trumbull Ladd’s “In Korea with Marquis Ito” to the James Bond henchman Oddjob — and how those views supported Japan’s occupation. After Japan surrenders in 1945, the KPG’s efforts reverberate through the postwar era in ways both true and fictional.

But this is only a third of “Same Bed Different Dreams,” which braids three plots together in a bewilderingly layered structure. One section, set in an alternate present-day New York, focuses on a once-promising writer named Soon Sheen who never followed up an acclaimed debut that had the misfortune of being published on 9/11. He now works for a megacorporation known by the Pynchonian acronym GLOAT, the meaning of which even its employees aren’t certain about (they joke that it stands for “Good luck on all that”).

Still peripherally engaged in the literary scene, Soon encounters an aging author named Echo, the “enfant terrible of South Korean letters,” whose novels are finally being translated into English by a small press. Echo is a portmanteau of the writer’s given name, Cho Eujin — an effort by the publisher to market his books to American readers. Echo’s translator tells Soon about an unfinished Echo masterpiece, a “hidden history of Korea” called “Same Bed, Different Dreams” (“We might lose the comma,” the translator notes). On the train ride home, Soon discovers the manuscript in his bag.

Personal Days A Novel Ed Park Random House: 246 pp., $13 paper

Thus, as we move through the intricate and revelatory story of Korea’s unheralded heroes and what might have been if their organization had continued on, Soon reads right along with us, commenting on its contents.

But there’s more. A third thread of Park’s absurdly complex novel involves a long-forgotten series of sci-fi novels published in the 1950s and ‘60s under the general title “2333.” These goofy space operas were the work of a Black Korean War vet named Parker Jotter, a fighter pilot who’d been taken prisoner after crashing his plane. In the late ‘70s, Jotter’s books are rediscovered when two board game developers are commissioned by a mysterious benefactor to adapt them into a complex game. The rules and logistics of the result, Galactic Legions, are uploaded into an early computer program that ultimately forms the basis of a software company. In the early 2000s GLOAT acquires the now-defunct company, which includes Jotter’s books and 33 boxes of his unpublished writing, and adapts the basics of Galactic Legions into an educational tool called Hegemon.

Although “Same Bed Different Dreams” is one of the most circuitously structured novels in recent memory, the reader is never confused about what’s happening in the practical sense. The path is always clear. It’s the connections between the disparate parts that make “Same Bed Different Dreams” succeed so powerfully yet enigmatically.

Park, a founding editor of the Believer, fills the caverns of his dizzying and intoxicating novel with echoes upon echoes. Characters both real and imagined recur throughout, sometimes showing up under aliases. Wildword, the name of a writing program in Soon’s story, appears later as the name of a psychological exercise similar to free writing. The initials KPG pop up numerous times. These reverberations assure the reader that wildly different events contain connections that will eventually be elucidated.

Jennifer Egan walks and talks — about ‘The Candy House,’ her sequel to ‘A Visit From the Goon Squad,’ and why she still believes in fiction and humanity.

For all its originality and effectiveness, “Same Bed Different Dreams” shares its approach with a number of similarly ambitious works — Anthony Doerr’s “Cloud Cuckoo Land,” Namwali Serpell’s “The Old Drift,” David Mitchell’s “Cloud Atlas” and Jennifer Egan’s “A Visit from the Goon Squad,” to name but a few. All of them juxtapose multiple narratives vastly separated by time and cleanly distinguished by form, mixing futuristic sci-fi or lighthearted comedy with the brutal vagaries of history.

“What is history?” the novel asks repeatedly, and though some answers are provided, no definition is satisfactory. But Park, who challenges our ignorance of Korea’s history, shows how a nation comprises more than geography, more than government practices, more than whatever name is bestowed upon it. A nation exists in the hearts of those who believe in its vitality and who fight for its sovereignty. History should work the same way.

Clark is the author of “An Oasis of Horror in a Desert of Boredom” and “Skateboard.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.