- Share via

On the Shelf

In the Pines: A Lynching, a Lie, a Reckoning

By Grace Elizabeth Hale

Little, Brown: 256 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

It isn’t surprising that Grace Elizabeth Hale chose to write a book about a 1947 lynching. The University of Virginia professor is an award-winning historian who has taught and written about the South and white supremacy for decades, including in the book “Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890-1940.”

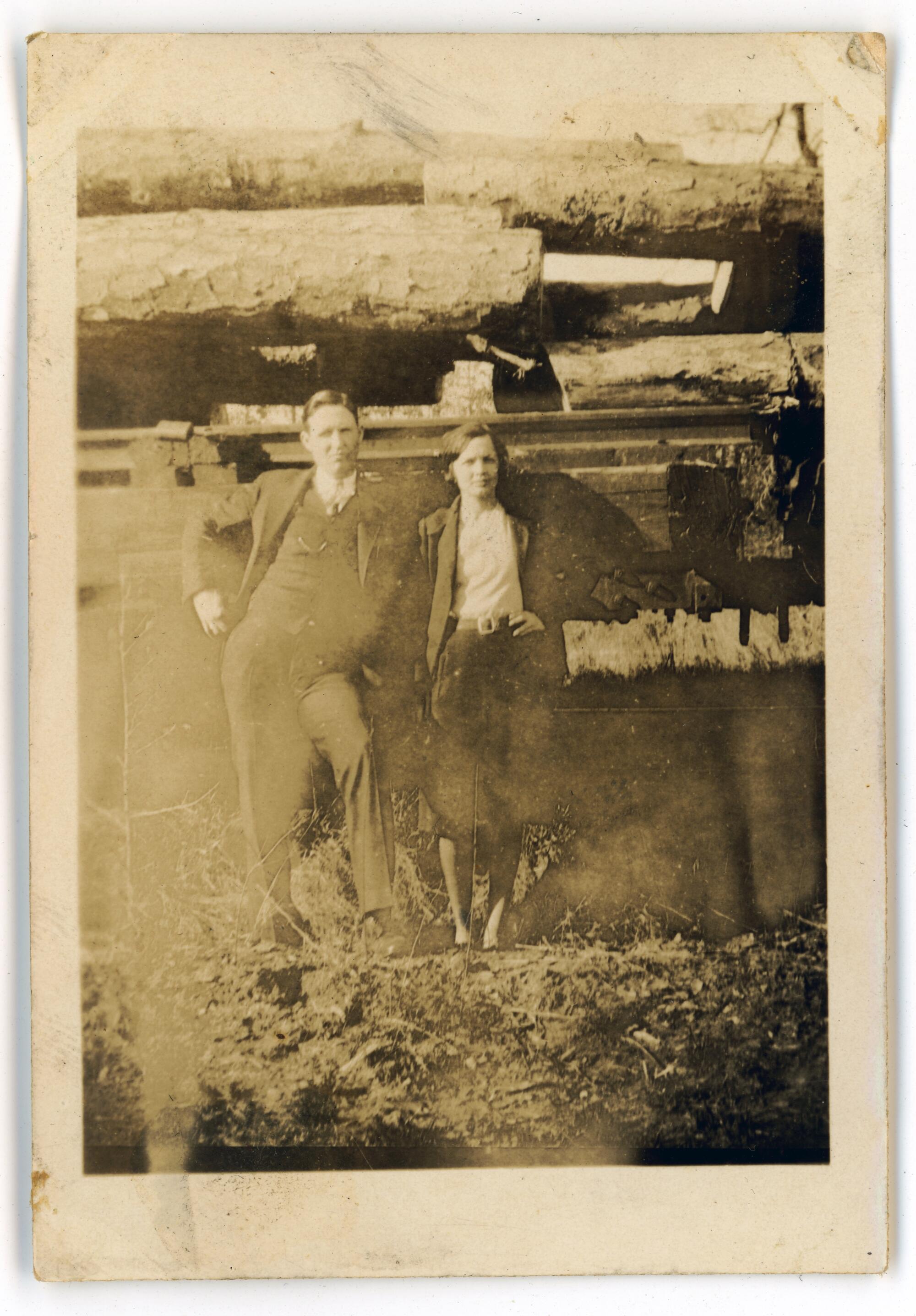

But her new book is more than just history from the archives. “In the Pines: A Lynching, A Lie, A Reckoning” is a family history of the worst sort. While growing up in Georgia, Hale had spent part of her summers with her grandparents in Jefferson Davis County in Mississippi. She was told that when her beloved grandfather, Oury Berry, was sheriff, he had given an Atticus Finch-esque speech to the townsfolk to stop them from storming the jail and dragging Versie Johnson off to a gruesome death.

Johnson was a Black man accused by local men of raping a pregnant white woman. But the woman never came forward; she may have been Johnson’s consensual lover. The prisoner died shortly afterward, purportedly during an escape attempt.

Even as a backlash brews over teaching America’s racist history, ‘Forget the Alamo’ and ‘How the Word Is Passed’ tell of the full, inglorious past,

In fact, Johnson was murdered by law enforcement under direction of the man Hale had known as Pa.

Hale started digging beneath the family lore back in graduate school. “I realized the story couldn’t have actually been true the way it was described to me,” she said in a recent video interview from her home in Charlottesville, Va. “But at that point I didn’t really want to know.”

Ultimately, however, Hale realized she couldn’t help the United States reexamine its history without reckoning with her own. She could “not stop looking” until the truth was laid bare. Our conversation, about her process and her discoveries, has been edited for clarity and length.

What motivated you to write this now?

What really drove me to write was [the Unite the Right Rally in] 2017 in Charlottesville. This is where I live. You saw those pictures of the people with the tiki torches surrounding that little group of students around the Jefferson statue at the Rotunda — those are my students. And [Heather Heyer] died just blocks from my house.

I can’t tell you how traumatizing it is to have white supremacists visit your town. They came for months because the city council voted to take down the Robert E. Lee statue, and I always felt like I had to be at the counter-protests. It made me realize that even though I thought I understood it all, there was something that I didn’t get, which was the visceral threat that comes when you have people with loaded guns parking their car in front of your house.

That made me think about a project that will make people understand that history isn’t distant and abstract — it’s us. All history is somebody’s family story. Frankly, that’s what gave me the courage to revisit this situation, because it was hard to do. I had grown up with a story of my grandfather’s heroism. And I thought my not wanting to know was symptomatic of a lot of white Americans. I wanted to make the point that this erasure of history is foundational to why racism and white supremacy persists.

Alt-right publications advocating white supremacy, misogyny and anti-Semitism are drawing ever larger audiences.

The thing that was most difficult to me was discovering the story — which I didn’t know until I started this research — that the sheriff before [Berry] stopped a lynching multiple times. That was just heartbreaking because it showed that it could be done.

You note that white supremacists saw their extra-legal behavior as serving their community. Does that feel connected to the way insurrectionists on Jan. 6 saw themselves as heroes saving the country? Is that the version their grandchildren will hear?

The concept that white male citizenship includes the right for you to personally embody the law is absolutely central. We celebrate autonomy and self-help in these rural communities, saying, “Look at these people, they know how to take care of themselves,” but vigilantism comes out of that too. When there’s an understanding of citizenship as limited to a certain group of people, whatever they do is somehow justified. We saw that with Ahmaud Arbery and with January 6th.

I’m trying to be a storyteller here, but I’m also a professional historian, and the history argument I’m sneaking in is that there’s a porous boundary between law enforcement and vigilante behavior. I don’t think it is strictly a Southern or rural thing. Most Americans don’t think about how different levels of the government — local, state, federal — are at cross-purposes with each other, and that these various levels often turn the other way or even encourage vigilante violence. That’s very much in play today.

Former U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey always wrote of public pain and private struggle. Her memoir, “Memorial Drive,” lets her mother speak.

You made a monumental effort to learn as much as you could about Versie Johnson — not just his death but his life. Why go to those lengths, beyond correcting the record?

Maybe that is the most personal part of the book. [She chokes up.] There’s nothing that I can do about these actions and his death, but I could bring him to life on the page to whatever degree I could, and acknowledge his life.

Do you regret not pursuing this story decades ago when more participants and witnesses would have been alive? Or would your research have been limited by the lack of information online back then?

I do regret not doing it earlier, because I would’ve found more people that were alive in the moment that the killing happened. But you’re absolutely right, the digitization of genealogical records was not there and it’s incredible what you can now find. I must say that while part of the reason then was that I didn’t want to know, this is very difficult, time-consuming research and I wouldn’t have been able to do it without the fellowship funding I got. Also, I’m a single parent, and so until my children were in college, I couldn’t be away for that long.

How did your mother and other family members react to your digging up the past?

Her choice was to not reexamine the past. This story is not something she accepts. It’s really hard for all of my family members and they didn’t get to decide. It was certainly something that they would’ve rather me not do. I just want to leave that at that.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.