Film critics Siskel and Ebert couldn’t stand each other. That’s what made their show great

- Share via

On the Shelf

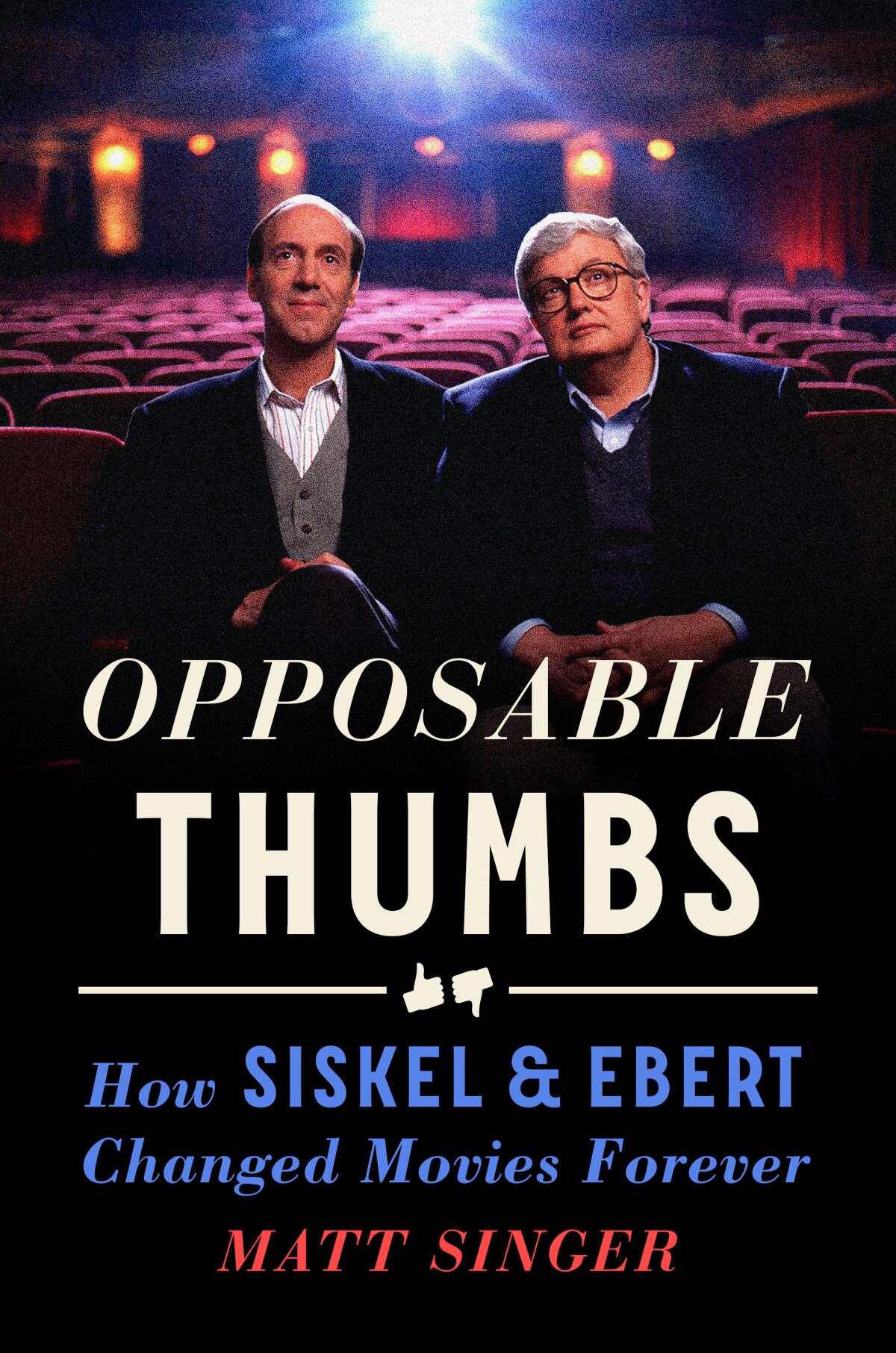

Opposable Thumbs: How Siskel & Ebert Changed Movies Forever

By Matt Singer

Putnam: 352 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

We called one of them “Fatty” and the other one “Skinny,” and surely we weren’t the only ones. When it came to our moviegoing habits, their word was the beginning and the end.

My mother, my sister and I watched “Sneak Previews” religiously when I was a child, transfixed by the sensation of seeing two people speak intelligently about movies on television. Our dependence led to some awkward moments, like when the three of us went to a matinee showing of “Blow Out,” the 1982 Brian De Palma thriller that begins with the dubbing of a porno movie. I was only 11, but both Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel had given the film enthusiastic “Yes” votes (they hadn’t yet adopted the whole thumbs thing). And so, “Blow Out,” with its ample nudity, violence and scariness, it was.

Such incidents might lead to sizable therapy bills. They might also help create a future critic.

After a few years of joining the Kindle cult, I am back to my old bibliophile ways. I do this not just out of compulsion, but aspiration.

Matt Singer, author of the new joint biography “Opposable Thumbs,” had his own formative experiences with Siskel and Ebert, who, as the book’s subtitle puts it, “changed movies forever.” As a middle school kid in suburban New Jersey, he would tell his parents he was going to sleep on a Sunday night, turn out the lights, and patiently wait until midnight, when the show, now simply called “Siskel & Ebert, ” would air in his market. By then the hosts had moved from PBS to the more lucrative pastures of syndication. Singer, another future critic, was hooked.

“Loving the show was just a fact of life for me,” he says over Zoom from his Brooklyn home. “I felt like it was this thing that I was obsessed with that nobody else cared about. It seemed very mine.”

Of course, Siskel, who died of brain cancer in 1999, and Ebert, who died in 2013 after his own harrowing cancer battle, which ultimately left him unable to speak, were hardly an obscure passion. Millions tuned in every week to see where their hugely powerful thumbs would point, and — just as important — to see them argue with each other in often shockingly personal tones. Frequent guests on late-night talk shows, where they always appeared as a package deal, they became celebrities to rival the stars about whom they opined.

But to a young person starting to develop a passion for movies, they were indeed a revelation: populist intellectuals, engaging and accessible, highly visible proof that one could actually get paid to write about movies. This in itself qualified as something strange and wonderful.

“Opposable Thumbs,” a lively accounting of the men and the various versions of their show, makes the author’s admiration for his subjects clear. But the book isn’t just a fan’s note. Incorporating thorough reporting and research, including hundreds of hours watching clips on YouTube, Singer gets at what made their partnership unique and far ahead of its time.

Remembrance: Roger Ebert, film’s hero to the end

Untelegenic movie critics for rival newspapers — Ebert with the Chicago Sun-Times, Siskel with the Chicago Tribune — they were thrown together in 1975 for what was then a radical new format on Chicago’s PBS affiliate, WTTW. The show’s awkward initial title: “Opening Soon … at a Theater Near You.” As Singer writes, “They didn’t know how to work on television, and they didn’t know how to work with each other.” They weren’t sure how to write for their new medium or how to use a teleprompter. The production lights glared off of Ebert’s humongous eyeglasses. It’s safe to say there was a learning curve.

Something else was abundantly clear from the start: These guys didn‘t like each other. This was decades before sports networks like ESPN began packaging screaming, combative hosts to manufacture hot takes for the sake of hot takes. Siskel and Ebert were highly competitive — especially Siskel, who couldn’t stand the fact that Ebert had become the first movie critic to win a Pulitzer Prize, also in 1975.

According to a Tribune editor quoted in the book, when Siskel would scoop his rival in print, he’d exult: “Take that, Tubby, I got him again.” Onscreen their rivalry gave the show an irresistible frisson, which I recall as a scary thrill for a childhood viewer: Are these guys about to throw down on TV? As late as 1987, when Ebert made Siskel apoplectic by giving a thumbs up to “Benji the Hunted” but not “Full Metal Jacket,” a sense of animosity lingered in the air.

“The tension was definitely real, and it absolutely made the show better,” Singer says. “There was drama and excitement. You didn’t know what they were going to say, and they genuinely didn’t know what each other was going to say. You’re watching their genuine reactions to each other, and sometimes they are horrified that they’re being blindsided.”

But when they closed ranks, they could be a mighty force, especially when they advocated for films that might otherwise get lost in the Hollywood shuffle. Among the small movies they pushed toward big audiences were Errol Morris’ “Gates of Heaven“ (1978), Louis Malle’s “My Dinner With Andre” (1981), and Steve James’ “Hoop Dreams” (1994). When they championed such films, they banged the drum for them over and over, through multiple episodes and features. “They gave me a career,” Morris says in the book. “Quite simply, I loved them.”

For me, film criticism has been on life support for many years.

Ebert and Siskel grew closer over the years, though that original competitive fire kept burning. And after Siskel died, as Singer points out, that chemistry proved unrepeatable. Ebert’s Sun-Times colleague Richard Roeper joined him for a spell, but they were friends, and you could tell. The beefs just weren’t as tasty. Once Ebert’s ailments forced him to step down, various iterations of the show appeared, some hosted by great critics, including A.O. Scott, Michael Phillips and Christy Lemire. But nothing could recapture that old black magic.

Singer has especially nice things to say about Phillips, of the Chicago Tribune (and formerly the L.A. Times), and Scott, of the New York Times, who co-hosted the show from 2009 to 2010. “They were extremely nice and thoughtful and good on camera,” he says. “But they didn’t have that tension, and it’s hard to fake that. If you like somebody, it’s tough to really go after them in that way that made the show so much fun to watch.”

Through all the replacements and imitations, it became clear that Siskel and Ebert were sui generis. Today you can go online and find umpteen pairs talking about movies, maybe even arguing about them. Most lack the seriousness of purpose, knowledge base and oil-and-water relationship of the original model.

Siskel and Ebert bustled into the world at a time when movie critics mattered more, before the culture fragmented into a million voices and “influencers,” and they ruled that world with iron thumbs. In this sense Singer’s book is a time capsule of a bygone era every bit as irreplicable as the partnership at its core.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.