In search of an erased African: An acclaimed French novel probes a literary scandal

- Share via

Review

The Most Secret Memory of Men

By Mohamed Mbougar Sarr

Other Press: 496 pages, $20

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The young writer is leaving Europe. He’s heading home to Senegal on the trail of a literary phantom. Diégane Latyr Faye, the primary narrator of Mohamed Mbougar Sarr’s novel “The Most Secret Memory of Men,” is obsessed with a book whose author has disappeared.

Sarr’s fourth novel, which won France’s 2021 Prix Goncourt, is dedicated to Yambo Ouologuem, the Malian author of another prize-winning novel, “Bound to Violence” (1968). “Secret Memory’s” missing writer is an echo of Ouologuem, who was celebrated in France and beyond before he disappeared in the wake of a plagiarism scandal. I first read “Bound to Violence” in graduate school, and found the history of the author’s rise and fall painfully gripping. Ouologuem’s fate seemed to point toward the precarity of Black literary fame. My copy of his book — the first English edition, which went to press before the scandal — proclaimed in large letters: “An African empire from the Middle Ages to our time comes blazingly alive in this black epic, hailed as the first truly African novel and awarded the Prix Renaudot.”

Sofia Samatar’s “The White Mosque,” a singular memoir about a journey through Asia on the trail of a Mennonite sect, tracks a personal search as well.

From “blazing” and “truly African” to fake, silenced, erased. Where was Ouologuem now? Back in Mali, my professor said. Rumors rustled around him. It was said he had taken a vow of silence. He’d become a recluse, a Sufi, a marabout.

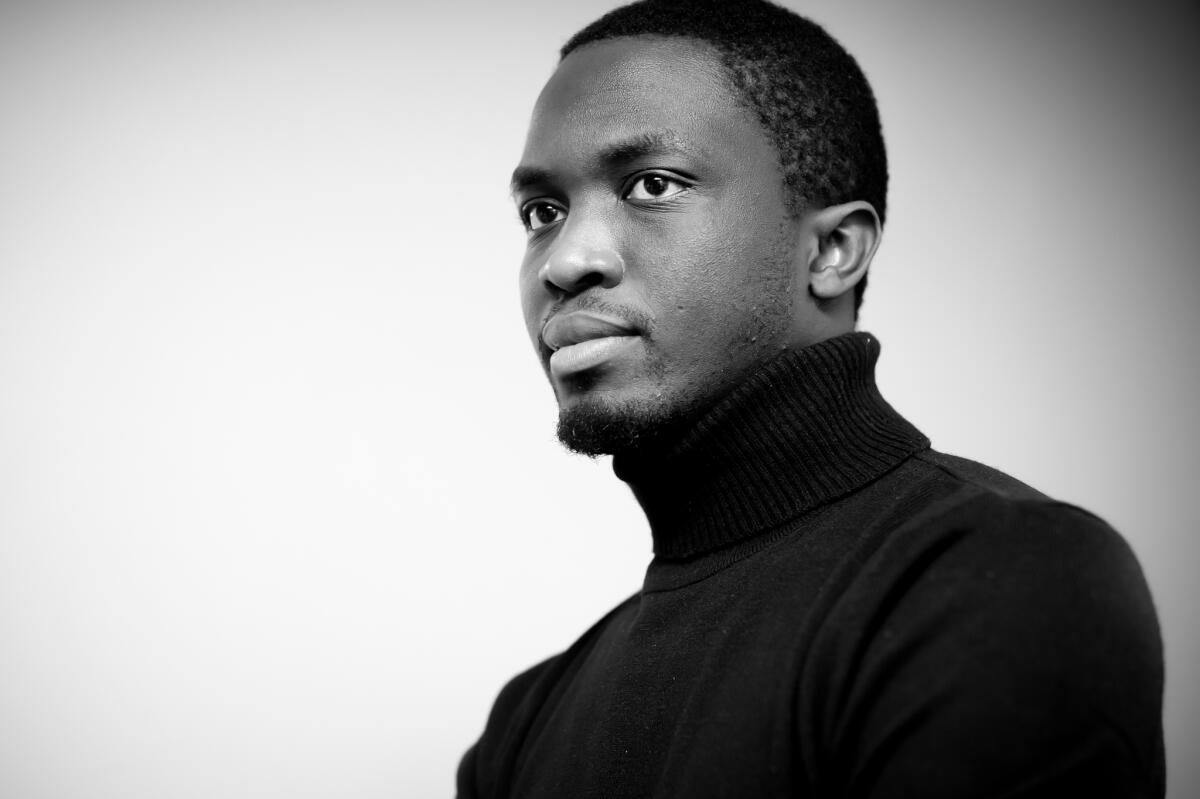

Sarr is the author of four novels, each of which treats a controversial subject. “Terre ceinte,” translated by Alexia Trigo as “Brotherhood” in 2021, examines terrorism; “Silence du chœur” addresses the migrant crisis in Italy; “De purs hommes” focuses on queer life and death in Senegal. In “Secret Memory,” Sarr turns his attention to the challenges of publishing while Black, exploring the gap between literature and the literary life.

That distance is vast, especially for the young African artists in Paris who form Diégane Latyr Faye’s circle of friends. They are tangled up in publishing parties, sex, talk of poetry and melancholy late-night walks — just like any band of aspiring literati but with an additional field of concern: the awareness of being African, of haunting the periphery of French letters. Faye and his friends are absolutely devoted to literature, but they’re also trying to make their way in France from its former colonies, a challenge that constantly draws them away from the solitude of writing and into the embattled scene of a narrow, exclusive literary culture.

This dilemma is thrown into relief when Faye, astounded by the power of “The Labyrinth of Inhumanity,” disgraced writer T.C. Elimane’s only novel, sets out to find its mysterious author. His growing file on Elimane includes reviews of the book — a funny and wrenching sendup of French literary culture that will resonate with Anglophone readers. According to critics, “The Labyrinth of Inhumanity” is the first authentically African novel; too good to have been written by an African; primitive and crude; a masterpiece by a “Negro Rimbaud”; “not Negro enough”; and of course, a plagiarism of Western literature. The Elimane file is a ludic tour of all the ways African literature can be erased: through contempt, through challenges to its authenticity, through a pious regard for noble savagery, through bemused and condescending politeness.

The National Book Awards longlist for translated lit includes David Diop’s ‘Beyond the Door of No Return.’ The rising star hopes to illuminate France’s ‘dark corners.’

“What pained him,” Faye learns about Elimane, “was that he wasn’t seen as a writer, but as a media phenomenon, as an exceptional Negro, as an ideological battlefield. In the press, hardly anyone talked about the text itself, his writing, his creation.”

“I want to write,” T.C. Elimane said. He came to France with this desire, a compulsion to immerse himself in literature, and produced “a singular book, never before seen, deeply original, but at the same time ... also a compilation of existing books.” This makes it like “Bound to Violence” and also like the novel in your hands, which takes its title from a line in Roberto Bolaño’s “The Savage Detectives” and claims a multitude of literary forebears. Many of these appear as characters in the novel: Jorge Luis Borges, Ernesto Sábato, Witold Gombrowicz, Silvina and Victoria Ocampo. Sarr’s novel is voracious, absorbing a world of literature from Homer to Haruki Murakami. It includes a host of voices and forms, skillfully rendered in Lara Vergnaud’s sensitive translation, from Faye’s diary entries to critical reviews of Elimane to the intricate oral narratives Faye collects during his search. The novel’s geography extends from Amsterdam to Buenos Aires with stops in Dakar, rural Senegal and the Democratic Republic of Congo, as if to leap over the question of center and periphery.

This is a bold response to the threat of silence: to say everything, to be all of literature. It’s also risky for an African writer, as the examples of Ouologuem and Elimane show. It was precisely their irreverent disregard of borders that incensed white readers for whom “that ambiguity was intolerable.”

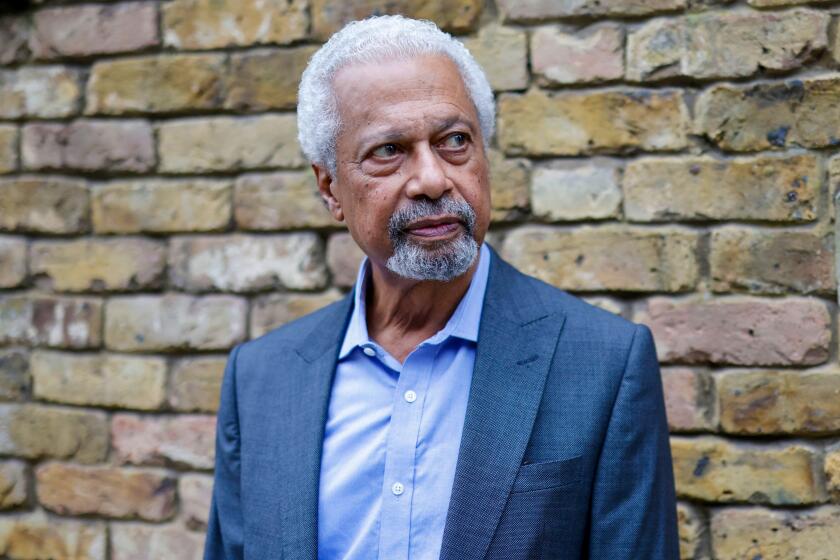

Much of the world may consider him obscure, but to generations of writers with African roots, Abdulrazak Gurnah is both an influence and a role model.

Ouologuem never published a book after he was accused of plagiarism. His silence unbroken, he died in 2017. Sarr’s path has been quite different. For Sarr to become the first writer of sub-Saharan African origin to win the Prix Goncourt, akin to France’s Pulitzer, for a novel about Yambo Ouologuem seems like a further chapter of the novel, history’s playful revenge. But “The Most Secret Memory of Men” is not about the struggle for recognition, however well deserved. In this novel, fame is a threat: The writer who seeks it may forfeit the silence at the heart of literature.

As Faye gets closer to finding Elimane, his quarry becomes increasingly spectral, almost a figure of nightmare who seems to warn Faye not to disturb his obscurity. Perhaps celebrity is the last thing Elimane wants. Perhaps what African literature needs is not an obliterating spotlight but an escape route into the solitude from which all writing springs.

Samatar is the author of five books, most recently the memoir “The White Mosque.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.