A novelist’s homage to the dumb humans of Yellowstone Park

- Share via

On the Shelf

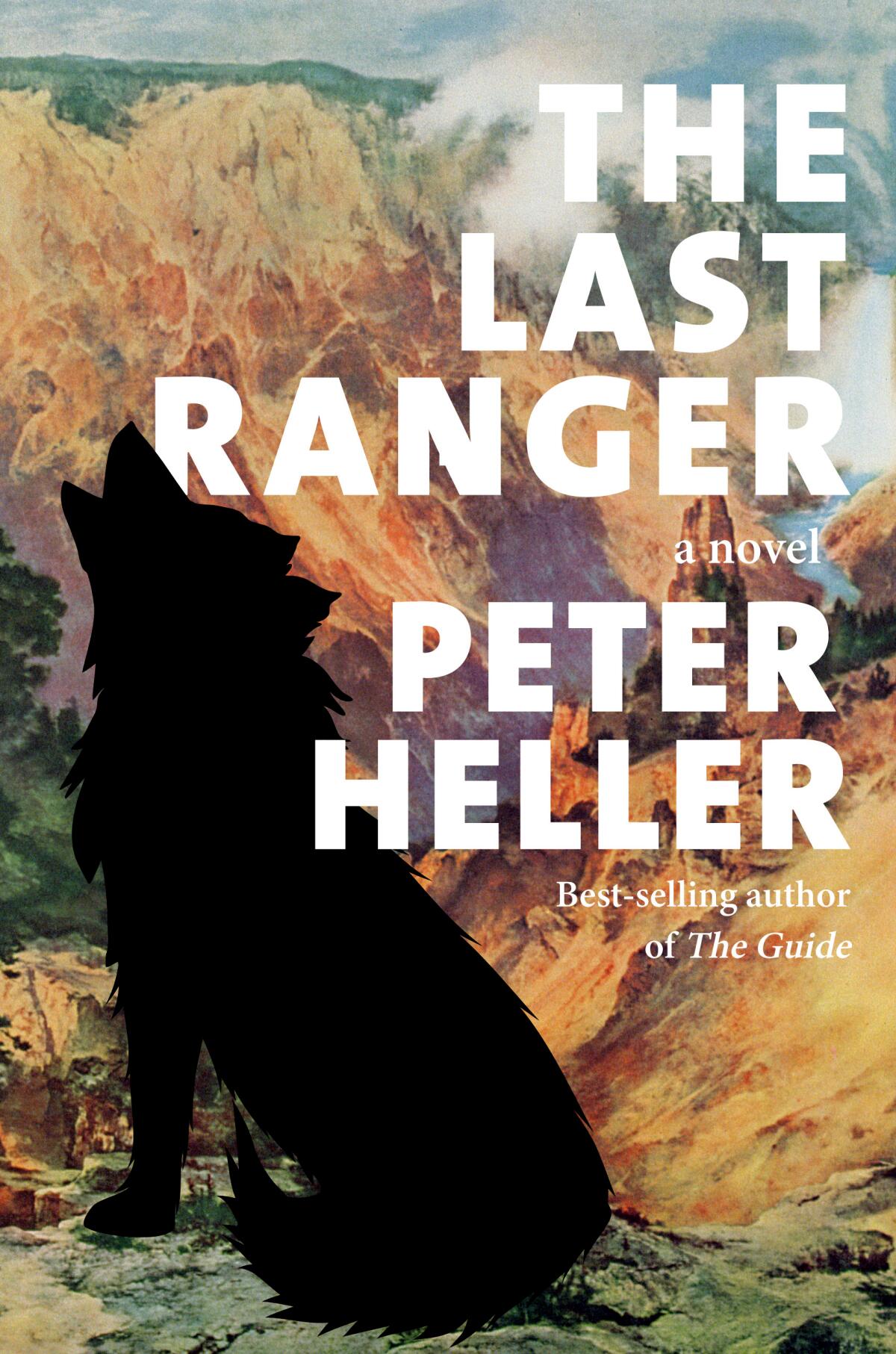

The Last Ranger

By Peter Heller

Knopf: 304 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The opening pages of Peter Heller’s new novel, “The Last Ranger,” will make you want to become a better human.

Ren, a youngish but seasoned ranger at Yellowstone National Park, has a literary bent — he once dreamed of becoming “a writer of the wild, like Merwin or Dickey or even Conrad” — but he also knows his way around bears and wolves and other wildlife. He valiantly saves a toddler from an imminent moose attack. He’s smart with firearms and smarter with people who are stupid with them. He goes fishing with such ritualistic focus, it feels like attending church. When he drinks, he gives himself a breathalyzer test before turning the ignition.

If the book’s title doesn’t make it clear, the novel’s early pages will: Ren is an endangered species, a nature lover who can handle an ever-shifting world with poise and know-how. He’s half Wallace Stegner, half Jack Reacher. But he also approaches his job with a certain arrogance, a feeling that his fellow humans are unworthy of the park that’s been preserved for their benefit. He’s proud of his role in “this enforced Eden,” Heller writes, even if it’s “enjoyed mostly by privileged folks from away who were on vacation, and where idyllic herds roamed and the lion practically lay down with the lamb—it galled.”

Discoveries: Surf’s up!

Messianic, him? One question Heller plays with throughout the book is whether all this rock-ribbed, superior-feeling sense of the world is covering up for something — and whether we’re missing something important when we long to be saviors. But before he gets too deep into that, Ren is concerned with hunting down a poacher named Les, who’s been hunting the wolves that have been carefully reintroduced into Yellowstone since the late ’90s. Hilly, a biologist friend of Ren with a deep affection for the wolves, tries to undermine Les’ efforts, only to end up near death with her leg in a trap for her trouble. Ren is compelled to save her, naturally. Once anti-government separatists enter the story, there’s much more to consider saving.

Heller’s style, which emerged in his 2012 bestseller “The Dog Stars” and was perfected in his 2019 eco-thriller “The River,” is Hemingway with the machismo scoured out of it. He can linger romantically on Yellowstone’s atmosphere: “The night went taut, like a drum skin, as if the solitary wolf had willed all of creation into a sounding board or bout for his song.” But his observations and dialogue are typically as clipped as Papa’s. Still, his tension within the natural setting is more psychologically nuanced. Ren has baggage, we learn in time: He’s a widower haunted by his mother’s involvement in an act of violence that blurs the lines between mercy and murder. When it comes to Les, the line between law enforcement and vengeance similarly blurs.

Amid Ren’s escalating anxieties — about himself, Hilly, the wolves and the separatists — is a parade of Yellowstone visitors who all seem to be in competition for a Darwin Award. He’s forced to intervene when two squabbling groups of campers get trigger happy, fumes at a drunk driver who’s killed a bison, rolls his eyes at tourists willingly putting themselves in harm’s way for the sake of a selfie. “How many innocent lives had been lost in service to Instagram?” he thinks.

Dean King’s ‘Guardians of the Valley’ follows the partnership of charismatic John Muir and erudite Robert Johnson to create Yosemite National Park.

The bits of comic relief are valuable, partly because Ren is such a serious character. “What’s wrong with me?” he thinks. “He might have added the thought, And why is my life nettled by that question?” Because the wrongness has many sources, the novel spreads in multiple directions. Ren investigates the Pathfinders, a group resentful of the government’s presence in Yellowstone (or anywhere, really). He studies up on Les’ past, which in turn becomes a study of his own wayward past. His saving Hilly stokes unwelcome memories of the wife he couldn’t save. All this in the context of a wilderness everybody wants a claim on, even the selfless ones. (“Are you going to bring in the man who killed my wolf?” Hilly asks, emphasis on the “my.”)

“The Last Ranger” can get convoluted in juggling all this, but it thrives as an old-fashioned duality-of-man drama. Ren may be more dirtied up by his troubled past than he wants to admit to himself; Les may have kinder, more understandable reasons for his actions than we know; both may have more in common than they think. It’s a durable trope that’s worked from Jekyll and Hyde to Kirk and Khan, but Heller is less invested in identifying winners and losers. Here, everybody has a “cross-grained stubbornness and iconoclast’s temper.”

The propulsiveness of the story sometimes overheats the prose: “You’ve been sailing under a false flag for years,” Ren chastises himself. And Heller is so determined to avoid easy heroes-and-villains storytelling that the novel closes with some facile both-sidesism, as if prey were better off understanding the nature of their predators.

If you look at the careers of Taylor Sheridan and Kevin Costner, one might reasonably conclude that the two were destined to work together.

But Heller means to suggest that just being ourselves automatically puts every one of us in contention for a Darwin Award; that we kid ourselves when we think of ourselves as immune to arrogance, recklessness and misunderstanding. Snooping on the Pathfinders, he laments: “Couldn’t humans leave the few remaining tattered patches alone? Voracious. Most voracious predator on the planet.” But he, like everybody, hungers too.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.