The key to Mike Davis’ brilliance: He never fit in

- Share via

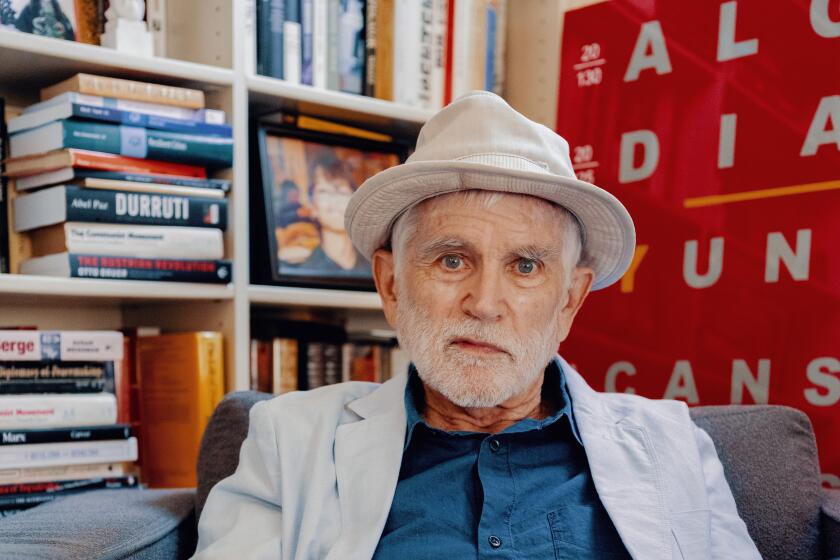

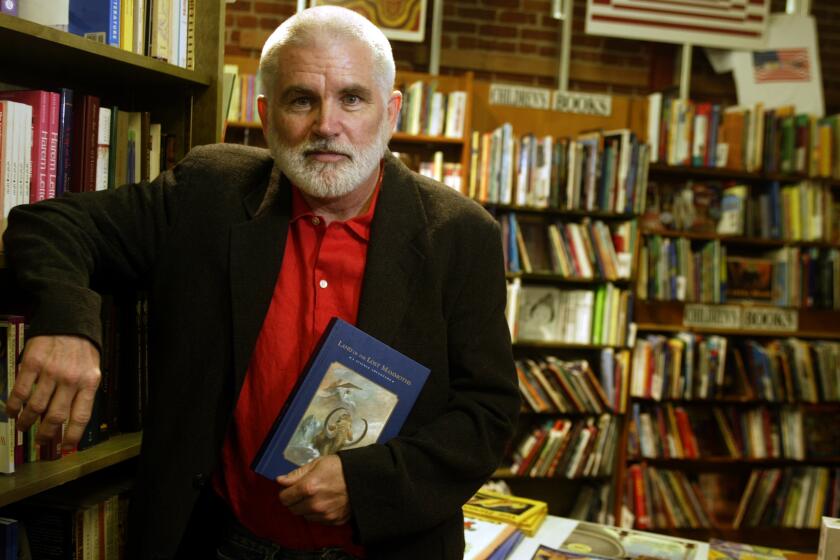

“City of Quartz,” Mike Davis’ masterpiece, was remarkable in many ways, not the least of which was the author photo, which became the focus of the Nation magazine’s review. There, Marshall Berman wrote that Mike looked like “an aging, ravaged light-heavyweight” who “doesn’t want company.” Berman confessed he was so turned off by the photo that the book “lay on my night table for weeks” before he started reading it. So began Davis’ ambivalent career in the intellectual trenches, declaring his independence by defying the convention of the warm, inviting author photo.

When Berman did get around to reading the book, he found it “gripping and original,” “Marxist in a refreshingly archaic way.” By “archaic,” Berman meant something specific. This was the era of postmodern theory, when Fredric Jameson had taken left-wing academia by storm with his 1984 essay, “The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.” There, Jameson celebrated Los Angeles’ downtown Bonaventure hotel as a delightful “hyperspace” that “expands our sensorium.” In “City of Quartz,” Mike went after Jameson, describing the Bonaventure as a “hermetically sealed fortress” in an area that aims to “ensure a seamless continuum of middle-class work, consumption and recreation, without unwonted exposure to Downtown’s working-class street environments” now reclaimed by Latino immigrants.

Mike told Adam Shatz in 1997 about the idea for “City of Quartz”: “I had this daydream of Walter Benjamin finally coming to L.A. and sitting in a bar with Fernand Braudel and Friedrich Engels. They decide to write a book about L.A. and divide it into three projects.” “City of Quartz,” he told Shatz, was to be the first volume of this “imaginary trilogy.”

But what does the title mean? Students have puzzled over that for decades. Quartz is sort of beautiful, isn’t it? Not for Mike: It is “something that looks like a diamond,” he told Shatz, “but is really cheap; translucent, but nothing can be seen in it.”

“City of Quartz” was pretty good for a guy who grew up in a household where, he said, the only reading material was the Bible and Reader’s Digest — and a guy who didn’t start out wanting to be a writer. During the ‘60s and ‘70s he became a full-time activist — ultimately an organizer for Students for a Democratic Society and a member of the Communist Party. His first engagement with the world of writing was a job as manager of the party’s bookstore in downtown L.A. Then, after working as a meat cutter — his father’s occupation — and a truck driver, he enrolled as a student at UCLA, met Marxist historian Bob Brenner, and after three years got a fellowship to study Irish history in Scotland.

With ‘City of Quartz’ and other influential works, Mike Davis shaped generations of thinking about Los Angeles and its origins.

His intellectual career began in 1974, when he met Perry Anderson, then-editor of the New Left Review. Anderson, however brilliant, did not provide the best model for an aspiring writer. One of my favorite sentences of his: “The peculiar esotericism of Western Marxist theory was to assume manifold forms: in Lukacs, a cumbersome and abstruse diction, freighted with academicism; in Gramsci, a painful and cryptic fragmentation, imposed by prison; in Benjamin, a gnomic brevity and indirection...” It’s an amazing sentence, but as a style it was hard to emulate, especially for a beginner — from Fontana.

In any case the aristocratic, Eton-educated Anderson saw the promise in the truck-driving student from Southern California, and in 1980 Mike accepted Anderson’s offer of a full-time job at the NLR in London.

He stayed for six years. Under editor Robin Blackburn, the NLR was publishing the most brilliant Marxist writers on the planet. Mike’s first two published articles appeared in the NLR at the end of 1980 — “Why the American Working Class Is Different” and “The Legacy of the CIO” (a “barren marriage with the Democratic Party”). It was also where Jameson’s boosterish essay on the Bonaventure appeared.

Mike returned to L.A. in 1987 and wrote “City of Quartz.” The book made him some unlikely friends, especially Kevin Starr, the bestselling semi-official historian of California, often considered the mainstream alternative to Mike. When we had an event at UC Irvine celebrating the 10th anniversary of “City of Quartz,” Starr was one of our speakers. Mike provided a warm and enthusiastic introduction; Starr interrupted, with a twinkle in his eye: “But Mike,” he protested, “you called me a Whig apologist!”

Defying convention eventually provoked the guardians of the mainstream. Never mind that Mike’s next book, “Ecology of Fear,” was number one on the bestseller list. With its stories about fires and floods and the coming end of Southern California’s “seismic siesta,” “Ecology” led first to further accolades — the MacArthur “genius” grant and the Getty Fellowship — and then to the “backlash of the boosters,” as I called it in an article for the Nation, defending Mike from the people calling him a “fraud” and going after his footnotes.

The influential author scrapped boosterism for a dimmer view of a city shaped by developers, politicians and a militarized police force.

Another mark of L.A.’s ambivalence toward its chief modern chronicler: Davis couldn’t get a full-time university job in the city that was his home. The USC history department sought a professorship for him but the institution’s administration turned them down. Mike left town for his first tenured job — at the State University of New York at Stony Brook — and with the money from the MacArthur he bought a house on the Big Island of Hawaii, on the wet side, in the jungle north of Hilo.

There, with his wife and two little kids, he wrote “Late Victorian Holocausts“ (2000), probably his most original and amazing book, analyzing the famines that killed 50 million Asian and African imperial subjects in the 1870s and 1880s, and how global climate shifts — the “mystery of the monsoons” — and their “murderous accomplices” among the colonial powers combined to create a new world economy.

The book was a dark one, but Mike said his year writing it was the happiest time of his life. “Utopia was our porch in Papa’aloa, Hawaii,” he told the Los Angeles Review of Books in 2012. “To write I need trade winds and laughing children. “

He continued to see things others didn’t — or preferred not to. He said he wrote about what scared him the most, and in 2005 he published “The Monster at Our Door,” the fruits of his studies of virology and what he called the “viral asteroids” threatening humanity. That seemed exaggerated and overdone — until winter and spring of 2020.

Next was “Planet of Slums” (2006), with that unforgettable first paragraph: “Sometime in the next year or two, a woman will give birth in the Lagos slum of Ajegunle, a young man will flee his village in West Java for the bright lights of Jakarta, or a farmer will move his impoverished family into one of Lima’s innumerable pueblos jovenes. The exact event is unimportant and it will pass entirely unnoticed. Nonetheless it will constitute a watershed in human history, comparable to the Neolithic or Industrial revolutions. For the first time the urban population of the earth will outnumber the rural.” You can see why Pope Francis would invite him to the Vatican after reading that.

Even in his final act, the legendary scholar and theorist does not mince words. He sees an L.A. that is decaying from the bottom up.

Then he started talking about a new project. In a 2003 interview with me for the Radical History Review, he said, “My day job currently is a grassroots history of Los Angeles in the sixties,” which would be called “Setting the Night on Fire.”

In 2007, an obscure Canadian bilingual English/French scholarly journal called Labour/Le Travail published a new piece of Mike’s, “Riot Nights on Sunset Strip,” about the kids fighting the cops in L.A. in 1967. He said it was “the first installment in a history of L.A.’s countercultures and protesters.”

Nothing more of the project appeared, but the idea kept coming up. Then on Jan. 1, 2014, he asked if I would co-author the book. He said he had too many unfinished projects going and wanted to make sure this one got written. I said, “Yes!” He said, “It will be a blast.” He was right.

In “Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties,” Mike continued to defy conventions. The book has nothing about ‘60s movies, pop stars or surf culture. The heart of the book is his narrative of the real outsiders, Black and Chicano young people. In the high school “Blowouts” of 1967-69, they demanded, of all things, a better education. And in the teachers’ strike of 2019, he wrote in the book’s epilogue, the children and grandchildren of those ’60s rebels walked picket lines raising many of the same demands. In that continuity, the refreshingly archaic Marxist found hope for “the young people of color who are Los Angeles’ future.”

Wiener is most recently the co-author, with Mike Davis, of “Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties”

The hailed and hated author opines on life, love and — his specialty — disaster

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.