How COVID prodded memorist Dani Shapiro to return to fiction and embrace the mess

- Share via

On the Shelf

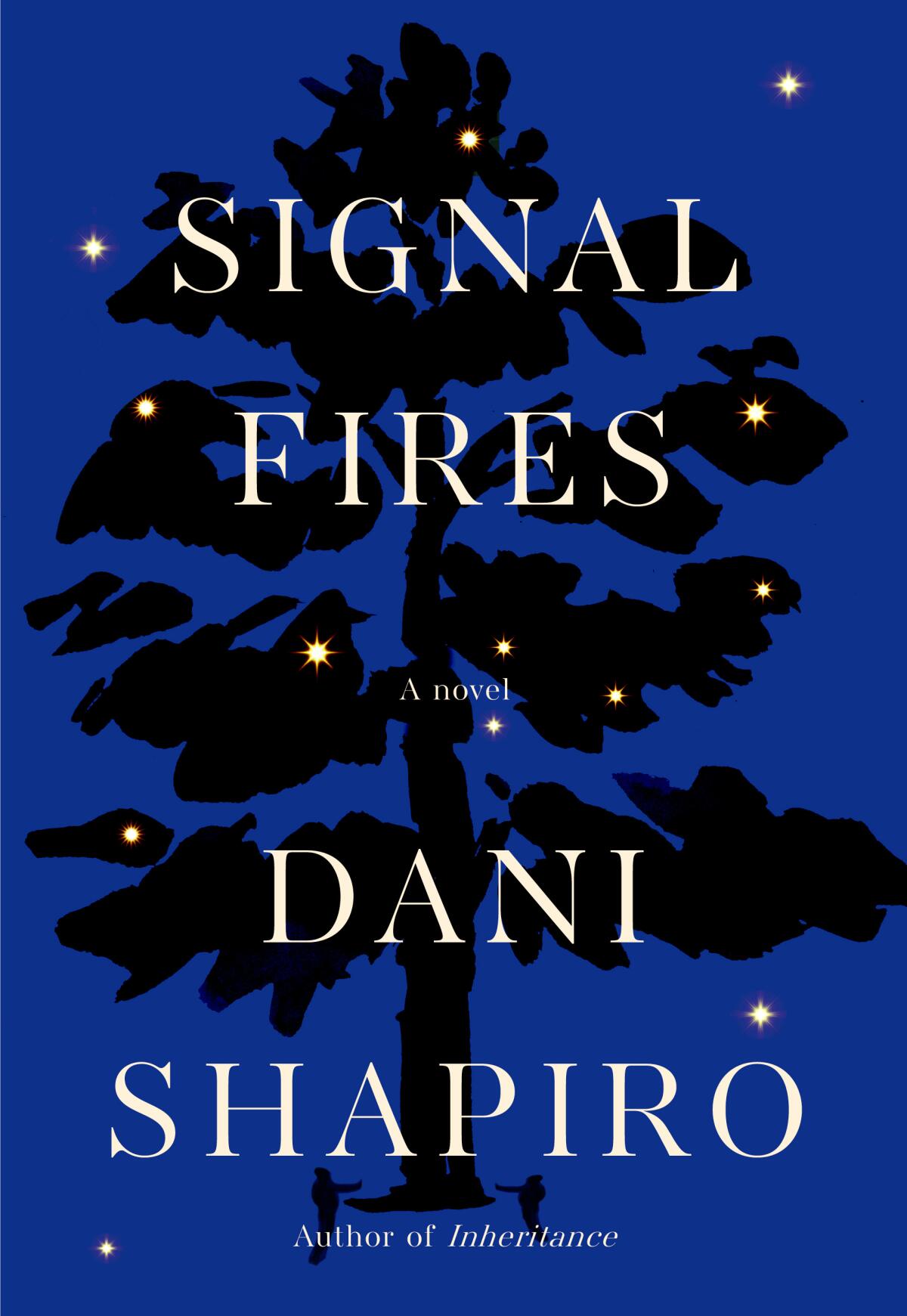

Signal Fires

By Dani Shapiro

Knopf: 240 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

As my spouse navigates bumpy, rainy backroads in upstate New York and I try to keep my smartphone pointed in the direction of the greatest number of bars, writer Dani Shapiro appears on my tiny screen, composed and serene in the upstairs study of her Connecticut home, with its shelf of books, colorful chaise and artfully chaotic pinboard. “Hello, Bethanne’s husband!” she says. “We appreciate you, thanks for your patience.” Despite our communication glitches, the author is unfazed, ready to work with my messy schedule.

Shapiro has been making things look easy since her debut novel, “Playing With Fire,” was published in 1990. Weaving deftly between novels and memoirs, publishing essays on craft, teaching at home and abroad and even — why not? — running a podcast, the author seems to move with frictionless grace between worlds and mediums while the rest of us squint at our creative lives and wonder where we’re going. And yet, as she soon confesses, she had to ditch her writerly compass to break the longest dry spell of her career — at least in fiction.

This month Shapiro releases her first novel in 15 years, “Signal Fires.” This development is sure to excite the diehard fan base she has built with her bestselling memoirs — from 1998’s “Slow Motion” to 2010’s “Devotion” and, most recently, the transformative “Inheritance” (2019), in which she tries a DNA kit as a lark, only to discover that her beloved father was in fact not her biological dad.

These memoirs have, naturally, informed her fiction, especially as they have matured — which in her case means they have become more and more fragmented. “I’m interested in the ways we don’t experience time in a linear fashion,” Shapiro says. “Memory, for example, isn’t linear. Imagination isn’t linear. We’re always walking around with all these versions of ourselves, bringing an inner crowd with us. I really wanted to find a way to do that in fiction.”

Authors used to expect to struggle as they gained experience. But now it is sell -- or else.

The task was easier said than done — although she has done it. “Signal Fires” follows two neighboring families in Westchester County, N.Y., over the course of two decades, showing how an early tragedy ramifies into the future toward a later cataclysm. In a construction as delicate as needlework but deceptively sturdy as one of Andy Goldsworthy’s stone walls, Shapiro shows in fiction what she’s spent decades teasing out in memoir: That our lives are ruled by subtle human connections we sometimes fail to understand because few of us are wholly plugged into the unseen forces that affect our lives.

The relationship between Shapiro’s memoirs and novels hasn’t always been symbiotic. When she wrote “Slow Motion,” about losing her father (and nearly her mother) to a car crash at 23, “I thought it was a sort of curative for my fiction — meaning that some events that had happened in my life were sort of haunting my fiction, and I wasn’t going to be able to write the kind of fiction I wanted to until I had told that story as a memoir.”

Shapiro wrote two novels before returning to nonfiction. “It was not some kind of conscious decision to switch teams,” she says. “I was pulled back. It was as if I had been digging for something that was just slightly beyond my grasp.” Until “Inheritance,” after which “I really had this feeling that that part of my body of work was complete.”

The toughest part of reaching the end of a road is not knowing what comes next. Shapiro had an idea for her next novel — the core story of Waldo Shenkman, which begins around the turn of the 21st century. Over time, Waldo becomes enmeshed with a neighbor family, the Wilfs, who are still coping with a fatal crash on their street decades earlier. Shapiro wrote about 120 pages and then shelved them.

You could blame it on the pandemic, except the pandemic hadn’t happened yet. Instead Shapiro was dealing with the whims of fortune, good and ill: the bounty that came with “Inheritance,” which led to a podcast about “Family Secrets,” followed by the calamity of the cancer that afflicted her husband, filmmaker Michael Maren. (He is now cancer-free.)

And then, during the early days of the pandemic, Shapiro was cleaning out her office closet, trying to restore order among “trash bags and piles of paper,” when “something made me sit down and reread this unfinished manuscript.”

The first ”lightning bolt” came from the pandemic itself. What would have happened to Waldo, she wondered? “What would he be doing in 2020? How would the pandemic have affected him and his family?” She also thought about Theo Wilf, a member of the other family. “I really wanted glimpses of them.”

Shapiro pauses for a moment. “Don’t we all want glimpses?” she continues. “Just a moment of seeing a future for a child, for ourselves? It felt like a future moment for my characters, and that’s when I understood what this novel wanted to be. That the pandemic would be a thin layer and it would not take over — but that it would give a kind of breadth and depth and dimension to the past.”

Jennifer Egan walks and talks — about ‘The Candy House,’ her sequel to ‘A Visit From the Goon Squad,’ and why she still believes in fiction and humanity.

Yet still she struggled with the timeline she had already been learning to break in memoirs. She wanted to tell the story in reverse chronological order, but it wasn’t cohering. The second lightning bolt came from a friend, a novelist who knew a few things about fragmentation: Jennifer Egan, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning, time-jumping novel-in-stories “A Visit From the Goon Squad.”

“I’d written myself into a corner because I was married to the big idea,” Shapiro says — the backward timeline. She remembers exactly where she was, talking with Egan on the phone in the car after dropping her son off at a piano lesson, when the novelist told her, “Chronology is boring. … You’re already [screwing] with time. You’re allowed to throw it all up into kind of a jumble.”

And this is where, finally, the author who has always projected control and polish, whose memoirs felt deeply composed even as they fragmented, realized she really had to let go — to embrace the mess of the world instead of trying to contain it.

That abandon has filtered down even to the title. Shapiro, who has generally limited her social media activity to tweets like “If you’re on here, you’re not writing,” found her new title on Twitter.

“Usually when I’m on Twitter, something is not going right with my day,” she said. “Yet every once in a while something amazing happens. On this particular morning the poet Ilya Kaminsky started a thread asking for pieces of poetry or prose that dealt with memory. One poem that came up was ‘Mourning’ by Carolyn Forché, and the phrase ‘signal fires’ leapt out at me. I knew as soon as I read those words that they would work for a novel in which all the characters were connected to one another as if by invisible thread. It captured something about the ways we are all interconnected.”

Shapiro is beginning to sound almost like someone who believes in serendipity, or at least in the idea that we never know what person, event or tweet is going to come into our lives and change us forever. Has everything she’s been through — we’ve been through — spawned Shapiro’s most spiritual work?

Bethanne Patrick’s October highlights include the biographies of Bob Dylan and Samuel Adams, new fiction from John Irving and Celeste Ng and plenty more.

“We don’t necessarily know who we are encountering and why they mean something to us,” she says. “During the time I was writing this book, I discovered my father was someone else, my husband, Michael, was very sick and then recovered. Like everyone else I went through many things. At the same time, after ‘Inheritance’ came out, I was meeting thousands of people who shared a profound connection to my story. And finally, the pandemic taught us all on a global level what it is to be all in it together. If anything spiritual infuses my book, that’s what it is.”

Patrick is a freelance critic who tweets @TheBookMaven.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.