How L.A.’s history of Black-Korean relations inspired a debut novelist

- Share via

Fall Preview Books

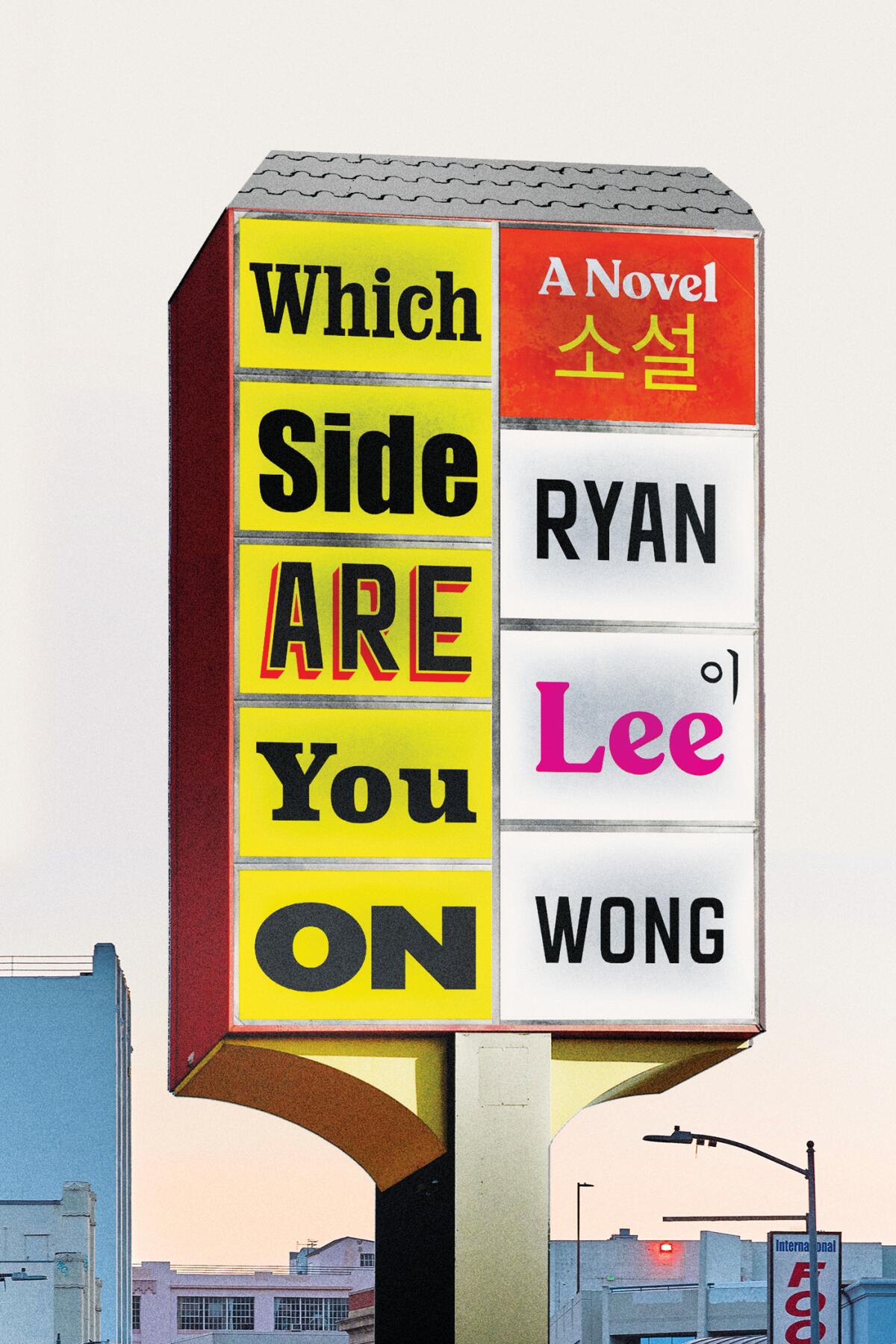

Which Side Are You On?

By Ryan Lee Wong

Catapult: 192 pages, $24

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

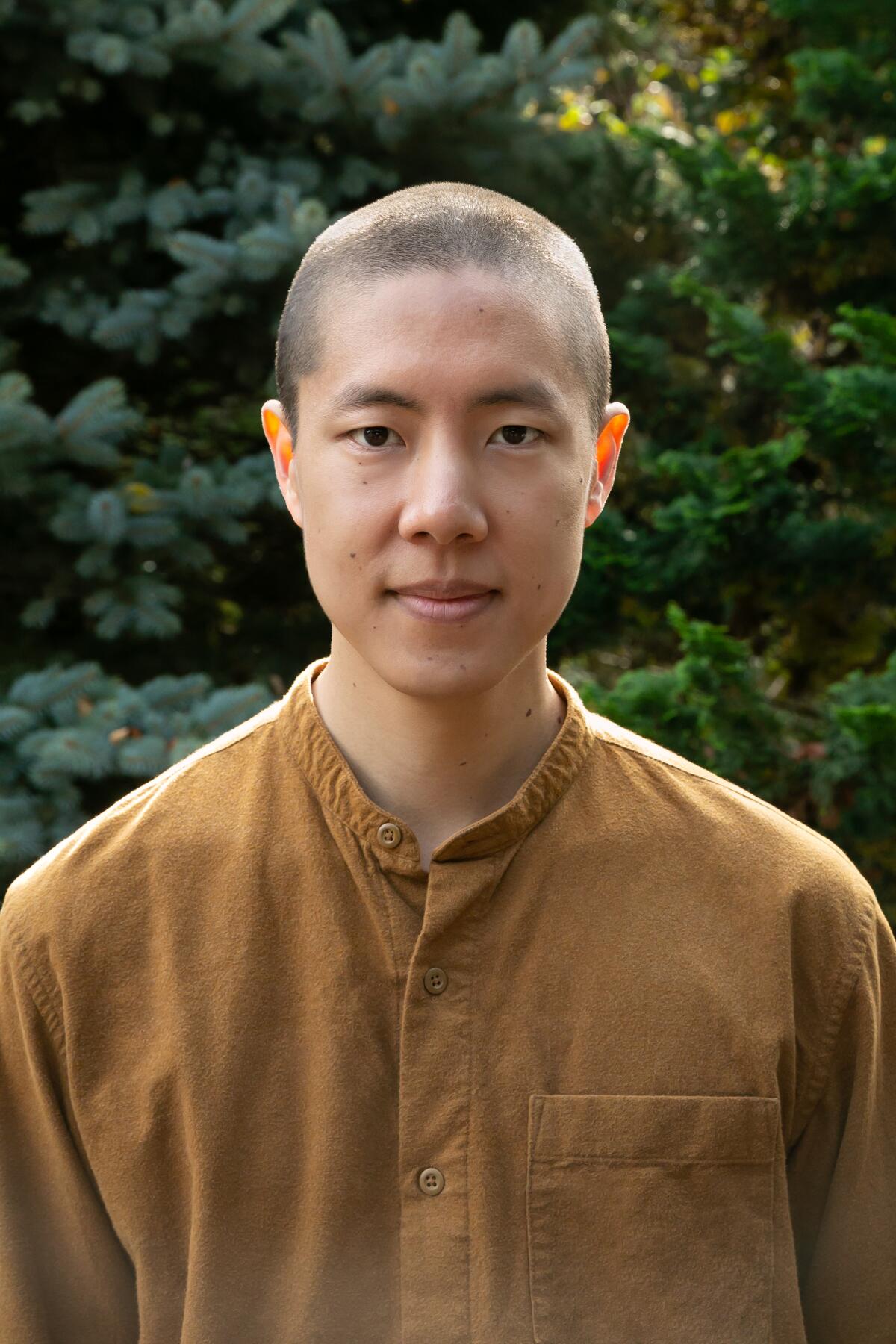

When Ryan Lee Wong set out to write a book in which characters debate history and ideas, he knew he’d be bucking tradition. The works he’d grown up reading about the life of the mind were set in cities built for long, ruminating walks — think of James Joyce’s Dublin. But his novel, “Which Side Are You On,” wouldn’t involve much foot traffic.

“I was like, ‘That can’t happen in L.A.,’” said Wong, 34, raised in the city but reached by phone in his current home of Brooklyn, N.Y. “No one’s like, ‘I walked from downtown to Koreatown and I had all these interesting thoughts about history,’ because they were driving.”

Instead, the conversations in his debut, out in October, evolve in strip malls, parking lots and, of course, cars — just as they did for Wong before he left for the walkable East more than 10 years ago.

Fall arts and entertainment picks from music, books, TV, arts and movies.

At the heart of “Which Side Are You On” is Reed, a 21-year-old Columbia University student dead set on dropping out of college to devote himself to the Black Lives Matter movement. On a visit back home, Reed and his mother zip around L.A. and embark on a series of transformative talks about organizing, racial justice and historical traumas.

“Ultimately,” said Wong, “this is a story about a mother and son trying to understand each other.”

That story was inspired by his parents’ roots in activism. His father, a fifth-generation Chinese American, was a union attorney and now leads UCLA’s Labor Center. His mother, a Korean immigrant, worked to forge a Black-Korean coalition under L.A. County’s Commission on Human Relations not long before the 1992 L.A. uprising, which was triggered in part by the shooting death of Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old Black girl, by Korean store owner Soon Ja Du.

Wong began writing the novel in 2016 when Peter Liang, an NYPD officer, was on trial for fatally shooting Akai Gurley, an unarmed Black man. Many Chinese Americans came out in support of the officer, who eventually was sentenced to probation.

“I suddenly saw this historical pattern that was repeating, where these two communities, Black and Asian, were being manipulated and pushed against each other by these larger forces of racism, and I wanted to understand what was going on,” said Wong.

But by the time the George Floyd protests erupted four years later, Wong was living in a Zen temple in upstate New York, his book still unfinished and his time diverted toward more spiritual pursuits. From the quiet, verdant plot overlooking the Taconic Mountains, he watched a new movement explode via his iPhone. “It reminded me again,” he said, “why this story had mattered to me in the first place.”

The novel he returned to benefited from its long dormancy; over the years, Wong’s rigid good-versus-evil worldview has slowly dissolved. Reed’s friend and foil, CJ, mocks his activist jargon as shallow and performative, and his mother teaches him that successful organizing involves persuasion, listening and patience.

On the pleasure and pain of the spiky footbed Adilettes.

“More and more I believe that in the face of a political situation or in the face of an emergency, you have to ask the questions, ‘Which side are you on? Where do I stand in relation to this?’” said Wong. “And at the exact same time, ultimately, there are no sides.”

That contradiction is what Reed comes to understand, just as his author did over the years he spent writing his L.A. novel of ideas: “That both are true at the exact same time.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.