Review: ‘Edie came from California’: A Sedgwick sister on the original influencers, Edie and Andy

- Share via

On the Shelf

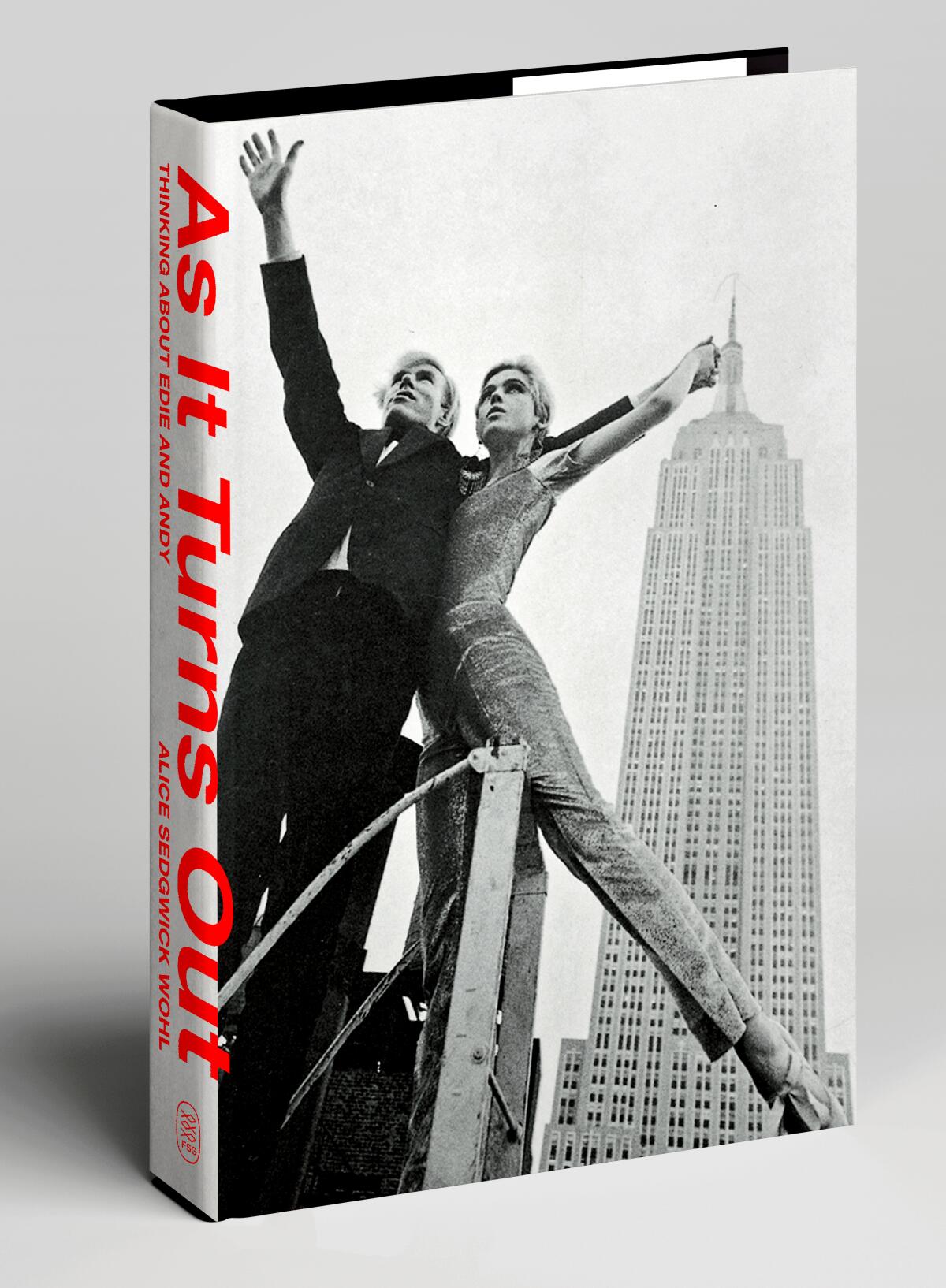

As It Turns Out: Thinking about Edie and Andy

By Alice Sedgwick Wohl

FSG: 272 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

A teenage Patti Smith saw a photograph of Edie Sedgwick in a magazine and traveled from New Jersey to Manhattan to stand outside clubs hoping to catch a glimpse of the Factory star. The romance for Smith came through what she saw in print. “Not even through records . . . I never saw people. I never went to a concert. It was all image.”

Had Edie never made it to New York, she would’ve been an “ephemeral and purely local phenomenon,” her sister, Alice Sedgwick Wohl, writes in “As It Turns Out: Thinking About Edie and Andy.” But Edie made it to New York and met Andy Warhol.

Sedgwick was an early “It” girl, catapulted to stardom by being Andy’s muse, the embodiment of the ‘60s Manhattan scene. After an early death from a drug overdose, she continued to fascinate, dissected by Jean Stein and George Plimpton in the oral biography “Edie: American Girl.” Wohl’s book is not a recollection or a mere revision but rather an attempt to understand the intense attention, even obsession, with Edie and Andy, and how their pairing anticipated the age of the influencer.

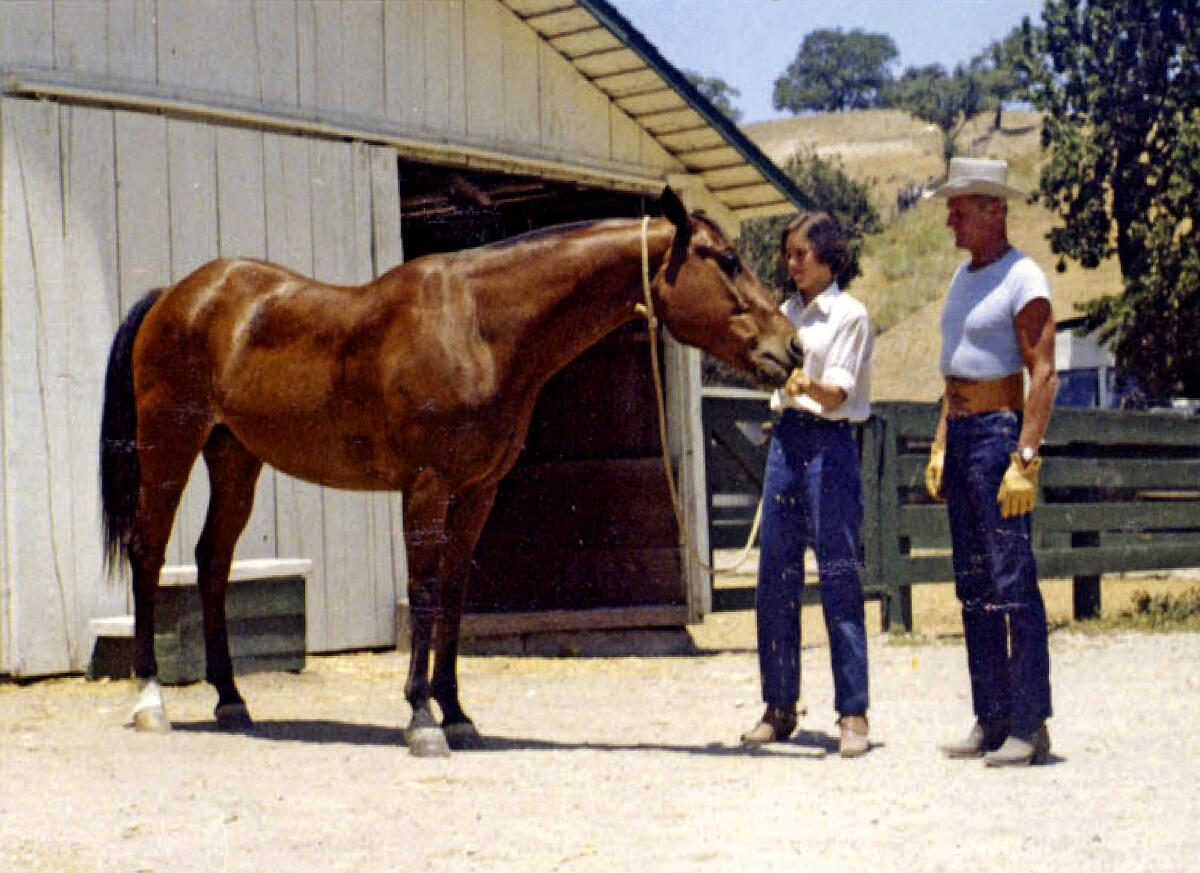

The fact that Edie made it to Andy is no small feat. Many assume Sedgwick was an heiress, a debutante, a “poor little rich girl.” This is partly accurate. First of all: “Edie came from California.” The Sedgwick children were raised on a ranch, inducted into the cult of “Fuzzy,” their megalomaniacal father. Fuzzy had had a breakdown before he met his future wife, and when the two got married his psychiatrist advised them that having children was not a good idea. They had eight.

“As It Turns Out” is divided into three sections. The first, “The Past,” is a chronicle of the Sedgwick childhood on the ranch: a gruesome depiction of raising cattle, an isolated existence of homeschooling and later boarding schools, and still later the suicide of Edie’s older brother. Wohl seeks not to reveal herself but to explain where Edie was coming from.

Blake Gopnik’s definitive ‘Warhol’ gathers up all the receipts on the blank icon who stormed the barricades of art, only to serve it up to commerce.

“I mention all this,” she writes, “because if it was true of me, it must have been all the more true of Edie when her turn came to leave the ranch, because the isolation in which we were raised only increased over the years, and in her case it was total.”

So Edie was not so much a “poor little rich girl” as a “feral creature springing out of captivity.” Her only desire was to be going somewhere, to be out and about. In Wohl’s words, she was always “zoom zoom zoom.” An addiction to uppers and downers and severe bulimia were overlooked by most who knew her because Edie was such a presence that there was no questioning anything she did. She just was, and what she was was perfect.

This is a book of Wohl “thinking about Edie and Andy.” Not thinking about Edie or about Andy or about how she saw Edie — because Wohl didn’t really know her that well. Wohl was 12 when Edie was born. “As It Turns Out” is only thinking about Edie and Andy as a joint venture.

Wohl has an obvious respect for Warhol as an artist. But she is surprised by her sister in Warhol’s films. Edie is magnetic. And Edie is not playing a part; she is not an actor. Wohl pins the breakup of the duo on Edie’s romance with Bob Dylan, who convinced her she could move to Hollywood and become an actor. Edie was no actor, Wohl writes. Edie was best at being Edie.

The second part of the book is simply titled “1965,” the year of Andy and Edie. It’s stunning to realize that all the things Wohl is describing — the films, the parties, the art, the relationships, the conversations, the photographs, the myth-making, the Factory and its superstars, the joint appearance on Merv Griffin, their grand entrance at the opening of the Andy Warhol retrospective in Philadelphia — all of it takes place within the span of a single year.

‘Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black’ collects the near-complete work of John Waters darling Cookie Mueller, who died at 40 in 1989.

That Andy and Edie anticipated this cult of personality — in fact gave birth to the age of the Kardashians, reality TV and social media, selfies and influencers — should come as no surprise to anyone with a smartphone. But it is eerie to see how far along they were in that game. “You have to remember that she had not grown up going to movies; there was no television on the ranch and no movie theater within forty miles,” Wohl writes. And of Andy: “Remember there was no such thing as video art … when Andy Warhol made this film.”

The film Wohl mentions is “Outer and Inner Space,” starring Edie and shot by Andy in 1965. In a close-up, there are two Edies. One is prerecorded and playing in the background, while another reacts to watching her own image. Which is the real Edie? Wohl quotes Warhol authority Callie Angell, describing “the tension that arises between the living reality of a person and the image that person is reduced to, a conflict she must literally act out, in real time, in this film.” Wohl’s description is essential to her (and our) understanding of Edie — but also to understanding ourselves, as we enact this tension on social media every day.

The final part of the book is “Notes for my dead brother.” Edie and Alice had not one but two brothers who died. First Francis, then Bobby, who drove his motorcycle into a bus and died right before Edie’s ascendance into pop culture superstardom. Wohl imagines this section as an epistle to Bobby, describing what became of Edie. By doing so she is trying to explain it to us, but more curiously, to herself.

A phenomenon is unknowable, perhaps. Edie lived only 28 years. “I know about her, but I don’t know her,” Wohl confesses to Bobby. What she knows is Edie’s pure magnetism, which, unlike Warhol’s Factory art, cannot be reproduced. Wohl writes of going to see “Factory Girl,” the 2006 film starring Sienna Miller as Sedgwick. “It was so fake it was painful, not because the actress wasn’t serious or talented but because it couldn’t be done,” Wohl writes. “Only Edie could be as she was.”

Beyond “The Dinner Party,” Judy Chicago’s feminist art has roots in Los Angeles and auto body paint jobs, as seen in a new show at Jeffrey Deitch.

Ferri’s most recent book is “Silent Cities: New York.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.