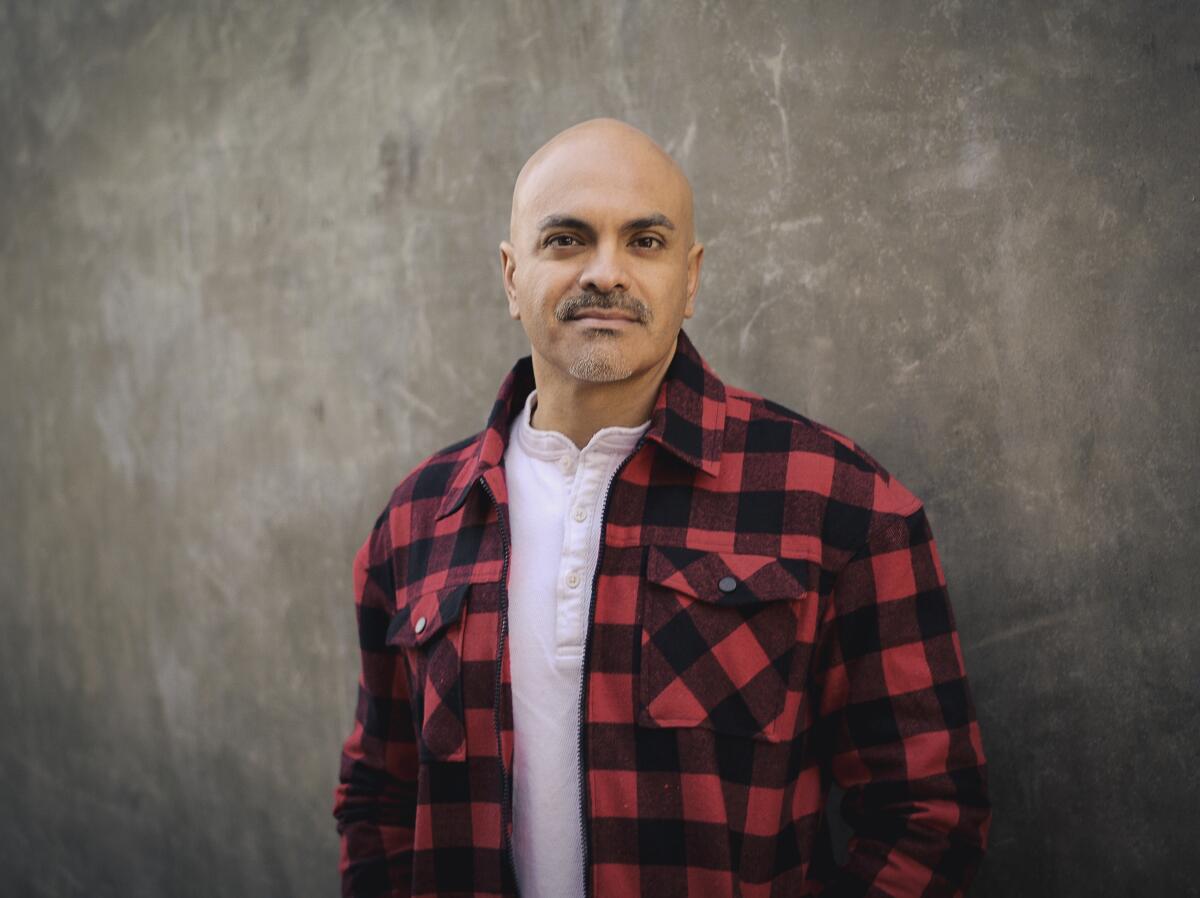

A ‘Jane the Virgin’ writer shares the story ‘Hollywood wasn’t quite ready to tell’

- Share via

On the Shelf

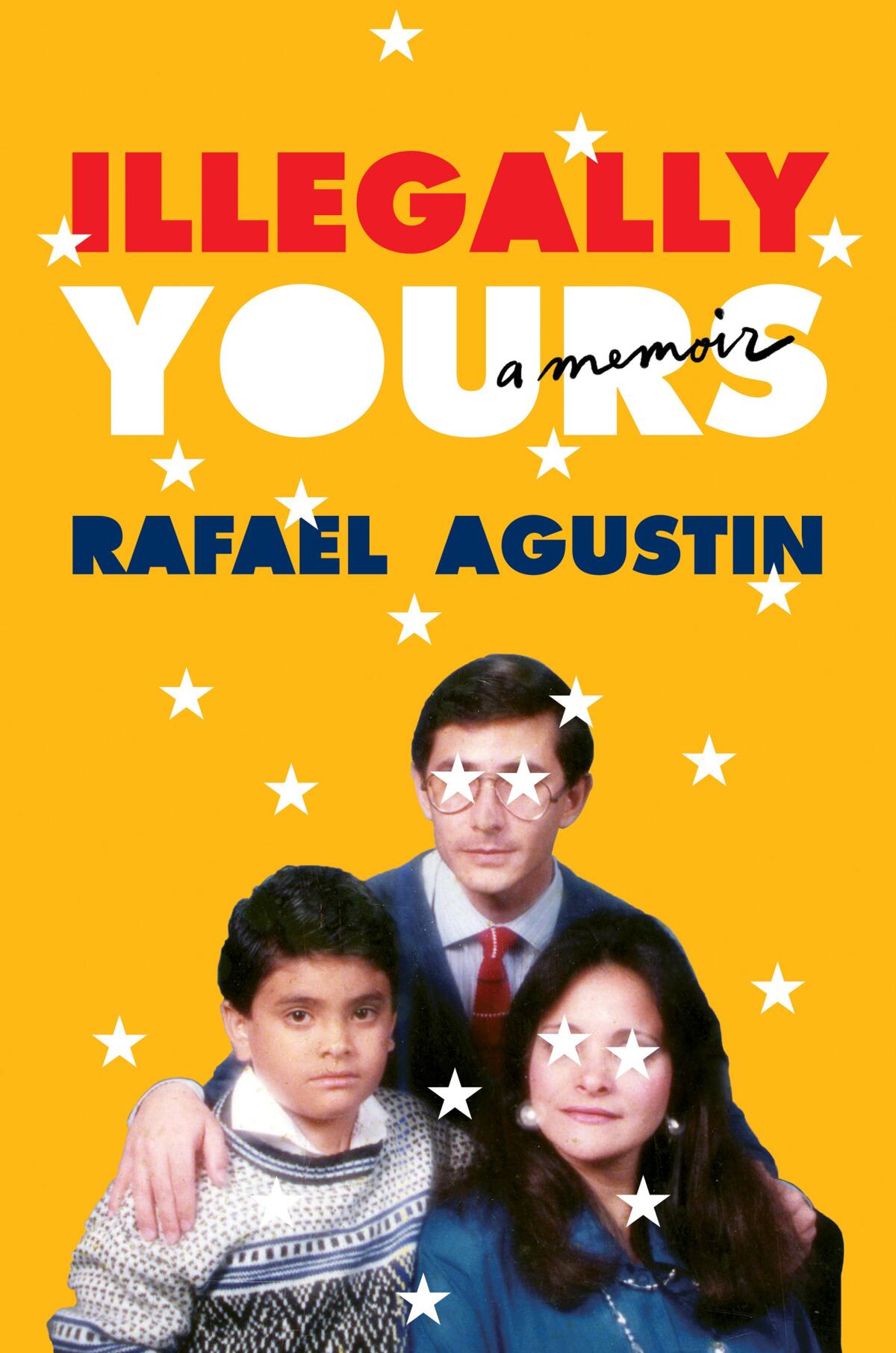

Illegally Yours: A Memoir

By Rafael Agustin

Grand Central: 304 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

There is something strangely fitting about the painting that looms behind Rafael Agustin during our video interview. The “Jane the Virgin” TV writer is discussing his new memoir, “Illegally Yours,” about growing up without documents in the Los Angeles area and succeeding against tough odds. The artwork behind him is a rendering of the Doors — Jim Morrison and the rest in their flamboyant ’60s glory.

To Agustin, 41, it all makes sense. His fascination with America and Hollywood began in early childhood; still in Ecuador, he adored “American Ninja,” pored over DC Comics and binge-watched Spanish-language reruns of Adam West as “Batman.”

A few years after his family arrived in L.A., an aunt was working as Oliver Stone’s nanny. “She had a bunch of his signed posters and I asked for one,” Agustin says. At 12 he wasn’t a Doors fan, but as his family bounced around from one Southern California town to another, struggling to hold on to jobs and pay the rent, he was enamored with the connection to wealth and fame.

“The cast [of ‘The Doors’] had given Stone this painting but he couldn’t fit it in with all his Picassos and whatever, so he had given it to [the aunt] and she gave it to me,” he says. Maybe, he adds, it subconsciously influenced his decision to attend UCLA, Jim Morrison’s alma mater.

Agustin’s circuitous path to college forms the heart of his memoir, which captures the uncomfortable mix of striving and alienation that marks so many immigrant journeys. His parents never told him he lacked legal status in America, even as they struggled to adapt. In Ecuador, his father and mother worked respectively as a surgeon and an anesthesiologist; here, they started at a carwash and a K-Mart.

Their secret allowed him to worry about fitting in with classmates, not about being deported. His mother later explained: “We didn’t want you to grow up feeling different. Because dreams should not have borders.”

But it also caused confusion: One day he and his father saw immigration officials chasing someone. When young Rafael asked a question in their native tongue, his panicked father warned, “Don’t speak Spanish.” Not understanding the implications, he felt ashamed, and refused to speak Spanish for years.

For decades, poets without legal status were excluded from prizes. A group called Undocupoets changed that — and then founded a prize of its own.

In his junior year of high school, Agustin brought home an application for a learner’s permit — and all of a sudden his striver’s journey hit a dead end. His parents finally explained his status, turning his world upside down.

“I was highly depressed after working so hard only to discover it was for nothing,” he says. Agustin was accepted to numerous University of California schools, only to feel gut-punched when they asked for a Social Security number. “It was crippling.”

He coped by burying his identity. “I decided I’d be the most popular kid in school,” Agustin says. “I became class president and prom king and a top 10 student so no one would ever suspect the truth about me.”

Outside of school, however, he learned to keep a lower profile. When a friend recently told Agustin she’d been pulled over for speeding, he confessed that he had never gotten a ticket. He wasn’t boasting, just commenting on how his life was shaped by not being in the country legally. “I’m always aware of where the police are,” says Agustin.

He says he never realized there were other teens in similar situations. Born too early for the Dreamer generation, he’s impressed by — even a bit envious of — the sense of empowerment shared by today’s immigrant youth.

Without that kind of network, Agustin initially floundered after graduation. Then he discovered two passions at area community colleges: theater and debate. He knows many who haven’t been so lucky. “There are people in my community more talented than me who weren’t able to rise up.”

The writer points to stories in the book about his friend Eddie, a talented Shakespearean actor whose school was riddled with gangbangers — and who never got the full opportunity to develop his talent. “When students from marginalized communities constantly hear ‘no,’ they stop asking questions in class, they disconnect,” he says. “When more privileged and affluent students hear ‘no,’ they get creative and try finding a way around it.”

For Agustin, it came down to supportive peers and mentors. “Finding people who were not disgusted with or ashamed of me but who were so concerned truly changed my life,” he says. “That’s when the ‘no’ stopped being crippling for me.”

After finally obtaining permanent residency papers and enrolling at UCLA, he found himself auditioning for plays by “dead white dudes.” He was safe from deportation, but representation still eluded him. He began seeking ways to create a better future for himself and other Latinos. He volunteered at the Los Angeles Latino International Film Festival, which had been co-founded by Edward James Olmos.

He also teamed up with two friends — one Black, another Asian American — to create a controversial stage show, its title a string of reclaimed racial slurs, that told the story of their America. “I wasn’t trying to announce myself as a writer or create a political statement,” he says. “I just wanted to perform and felt I had to write myself into existence.” The play ultimately toured for years, playing in 44 states.

Soon afterward, he wrote a pilot for a TV show, tentatively titled “Illegal.” In 2017 it went into development with “Jane the Virgin” star Gina Rodriguez — but seven years later nothing has come of it.

“The ‘Illegal’ pilot is what truly launched my career,” Agustin says. “It made me a Sundance Fellow, it got me my Hollywood agent, it got me staffed in the writers room of one of the best shows on television, and it got me my first TV sell. However, Hollywood wasn’t quite ready to tell a story about an undocumented American family back then. Perhaps — with this book — they will be now.”

These experiences have combined to give Agustin, now an American citizen, a measure of hope — as well as skepticism. “I started this memoir with the simple question: ‘What does it mean to be American?’ I couldn’t avoid the harsh realities.” Although his memoir doesn’t preach politics, he insists on illuminating the perils of an imperialist foreign policy, an inhumane immigration policy and a ruthless capitalism that often fails to provide equal access to the American Dream.

“Immigrants, and especially undocumented immigrants, have this abusive relationship with America,” he says. “We love this country so much, and it just won’t love us back. But we’re going to stay and take the abuse and hope that one day America will see the error of its ways.”

Watch Karla Cornejo Villavicencio and Marcelo Hernandez Castillo at the L.A. Times Book Club

Never mind that Agustin has personally thrived. It was important to tell his immigrant story not despite his success but because of it. “In Hollywood,” he says, “there’s a thing called symbolic annihilation, where certain stories are not told so it’s easy to vilify people or think of them as others. I want people to understand that we’re all in this together.”

He also continues to help those who have followed him. Today he is CEO of the Los Angeles Latino International Film Festival, where he once volunteered, and executive director of its Youth Cinema Project.

And Agustin still has that Doors painting. After a quarter-century of lugging it from one apartment to another (and a failed attempt to sell it to Tower Records long ago), this old, extravagant hand-me-down from a famous director to an immigrant service worker has become a sort of marker of his family’s progress. “One day,” he says, “I’ll meet Oliver Stone and tell him the story.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.