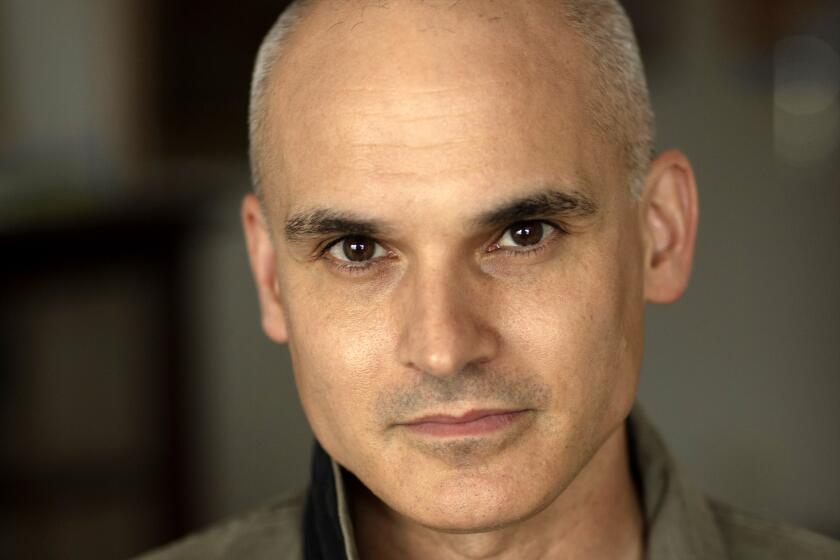

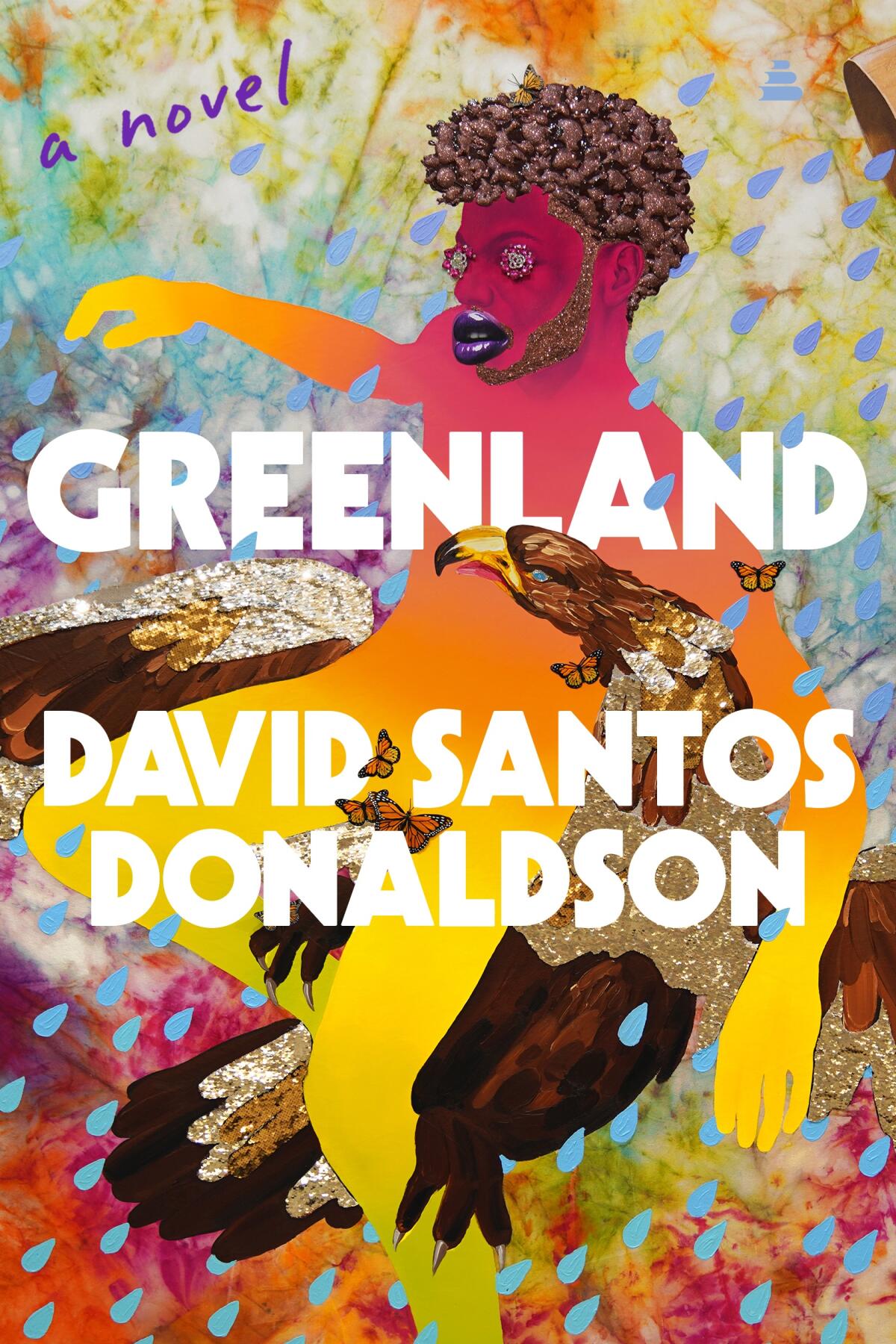

Review: A Black gay novelist explodes the margins, with help from E.M. Forster, in ‘Greenland’

- Share via

On the Shelf

Greenland

By David Santos Donaldson

Amistad: 336 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The novel-within-a-novel is nothing new; nor is the novel-as-time-spanning-cultural-interrogation. David Santos Donaldson’s debut, “Greenland,” is certainly both. But not since Iris Murdoch’s “The Philosopher’s Pupil” have I read a novel crammed full of so many ideas and tropes that they threaten to spill out of its margins.

Ostensibly about a young queer man in Manhattan, “Greenland” is also a novel of identity and place, but it is less about claiming one’s own territory than deciding who gets to come inside. As the story begins, Kip (short for Kipling) Starling has barricaded himself in his basement study with “five boxes of Premium Saltine Crackers, three tins of Café Bustelo, and twenty-one one-gallon jugs of Poland Spring water,” determined to write the novel an editor has told him she’d read if he could finish it in three weeks.

“All my life, through all the various ups and downs, I’ve only had one enduring dream: to be a published writer,” Kip tells us. Besides, he adds, “I’m useless at anything but writing.”

Kip had wanted to write a novel about the great (and long-closeted) English novelist E.M. Forster and his young lover in Egypt, a tram ticket collector named Mohammed El Adl. When the editor demurs, he begs her to share what kind of novel would catch her attention: “’Well,’ she said, focusing on me again, speaking firmly, ‘perhaps if you were to tell it from the perspective of Mohammed. That would be interesting!”

As you’ve likely already gathered, Kip has issues. Mommy issues, daddy issues, husband issues (his spouse of seven years has just asked for a divorce) and much, much more. If he didn’t, he probably wouldn’t attempt to write a novel in three weeks, let alone lock himself in a room with meager rations. He’s not just looking for a book deal; he wants answers: “What if Mohammed wants to tell me about his experience so that I know, from his perspective, where we queer, Black, colonial men have come from?”

Our regularly updating 2022 Pride guide to culture will feature novels and memoirs from LGBTQ icons, must-see TV series, music, movies and much more.

We know about marginalization. (So does Kip’s editor, who sees commercial value in focusing on the “Other” in the Forster relationship.) Yet Donaldson wants us to consider those like Kip, like Mohammed and like himself (a Bahamian New Yorker), who feel excluded even from the margins. People who have been raised with the habits of colonial life but not membership therein, whose combined identities leave them belonging precisely nowhere. Kip has moved from England to work on his MFA at Columbia University, where he feels snubbed by a community in which he’s not Black enough, not queer enough, not anything enough for anyone. “Here I was with my Black gay brothers and I was still the pariah. Would I ever fit in anywhere?”

And so Kip places his hopes, perhaps foolishly, in book publishing. If Donaldson did nothing else in this novel but tell Kip’s story, his sensitive investigation into isolation would make it notable. Kip confesses that he’s been “obsessed with the idea of being recognized by the publishing world” because “for some surely problematic reason, as a Black, gay man, I need the world to say, I see you. You matter. I know you exist!”

Yet Donaldson is after something larger than literary New York’s blind spots. The braided narrative skips between Kip the frustrated 21st century novelist, Mohammed the 20th-century gay Black Egyptian and “Kip,” a character in his own novel “The Nowherians” — yes, the nowhere men. These toggles aren’t merely fancy jump cuts; the stories and eras blur together like overlaid transparencies. In one powerful juxtaposition, Mohammed is attacked by a British soldier: “He bashed my skull, and I went numb. But it was only when he held his boots on my neck, pressing down so that I could no longer breathe, that I knew, for certain, I would die.”

Some pages later, Kip, recalling incidents of police brutality against Black Americans, brings up many familiar names — Till, King, Diallo, Rice, Garner, Castile, Lopez, Martin “and so many more that I can’t even bear to go on naming them” — but never Floyd. We understand that his story has already been accounted for.

‘Trust,’ by Hernan Diaz, is a Rashomon-like concoction of four stories about a hollow great man — fascinating and assured, but ultimately deflating.

Amid all this is a lot of sex — all of it meaningful in Donaldson’s hands. One man refuses to let Kip penetrate him, saying he’s saving himself for their wedding night. He declares his love by giving Kip a Glock 22, a gun as Chekhovian as they come. Its discharge will prove essential to Donaldson’s finale, the happiest unhappy ending you’ll ever read — or is that vice versa?

The narrative braid, meanwhile — the overstory — grows more tangled. As Kip makes progress on his novel, Donaldson’s progresses into the realm of spirituality and magic. The author is a practicing psychotherapist; he must be a Jungian at heart, given the archetypes that inhabit this book: the repressed Englishman, the passionate young lover, the long-suffering spouse.

Most of these are male, but one of the most important characters is the Great Goddess Tatha-agata, who shapeshifts variously into a sultry Southern voice, an unstoppable erotic charge, an Inuit baker and a staid Black matron on an airplane. Perhaps the missing part of these men’s psyches is actually their inner femmes, the warm, caring and intuitive parts of them that have been beaten down and beaten out by their upbringings and cultures and educations.

Or at least that’s part of it. “Greenland” (the title refers to where Kip winds up after a sudden deplaning en route to London) runs over with philosophy, psychology, politics, literature, family sagas, food, beauty, style, history, geography. This is a book with respect for neither the margins of the page nor those that confine us in the real world. Some may find its bountiful overflows confusing or unnecessary; I found them mostly captivating. Whatever your personal tolerance for the disorder along the way, Donaldson sustains a plot that ends with ecstasy, action and reconciliation, satisfyingly concluding a novel of ideas that is also about one queer Black man finding his true north.

Anton Chekhov’s influence is seen in the Oscar-winning film “Drive My Car” and recent novels by Gary Shteyngart and Rachel Cusk. And stage productions, including a new “Uncle Vanya” at Pasadena Playhouse, are revealing just how collaboratively open his plays can be.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.