Review: Emily St. John Mandel gets back to the future

- Share via

On the Shelf

'Sea of Tranquility'

By Emily St. John Mandel

Knopf: 272 pages, $25

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

There is a small moment in Emily St. John Mandel’s new novel, “Sea of Tranquility,” that you might miss: A man recalls, from his childhood, a moment when his mother glanced at a photo of the “Earth Ocean” while stirring soup. Four centuries from now, their family lives on Colony One, a human-engineered city with a manufactured river but no seas or oceans.

This man, Gaspery-Jacques Roberts, has private fixations of his own. He may be mysteriously connected to someone who lived many years ago, or at least to her imagination. Novelist Olive Llewellyn included a character named Gaspery in her smash-hit bestseller “Marienbad,” which was released in the 23rd century.

Llewellyn, in another section, is haunted by the success of “Marienbad,” a dystopian novel she wrote on the brink of an actual pandemic. The parallel to Mandel herself, who is also the married mother of a young daughter, has to be intentional. Mandel was virtually hailed as a prophet — a designation she disliked — after her pandemic-dystopian 2014 bestseller, “Station Eleven,” was adapted into a hit HBO Max miniseries just in time for COVID-19.

Llewellyn too plays the reluctant seer. One of the novel’s most affecting sections unfolds as she realizes her suspicions about a coming virus were correct; she cancels the rest of her book tour and heads home, weeping along the way, stripping off her likely contaminated clothes on the sidewalk.

“Sea of Tranquility” might be Mandel’s “pandemic novel” in the sense that it’s the one she wrote over the last two years, but it documents a different kind of human glitch. As the story opens, a young British man, Edwin St. Andrew, experiences a strange suite of sensory events in 1912 in a Canadian forest, where he meets a man named — yes — Gaspery Roberts.

Emily St. John Mandel’s last novel, “Station Eleven,” envisioned a pandemic. “The Glass Hotel” plumbs financial doom.

Mandel knows how to brew a story. As Edwin, Gaspery and other people scattered across time — a teenager named Vincent, an aging violinist named Alan Sami — all experience similar visions, we settle in for a juicy sci-fi ride, replete with time travel, lunar colonies and robot landscapers. But Mandel is less concerned with the mechanics of science fiction than with using its tropes to chart new courses through human relationships and their consequences.

At the farthest edge of “Sea of Tranquility’s” time frame, it’s the turn of the 25th century, Gaspery’s native “present.” He is looking for new employment, and his sister Zoey works for the mysterious and powerful Time Institute. The concept of time travel has been widely accepted, and its bylaws call back to the most familiar sci-fi (from Ray Bradbury to “Back to the Future”): Don’t tell anyone about your mission. Don’t stand out. Don’t interfere with a person’s life, even to save it.

The book jumps across time with impunity, following an internal map that will make exquisite sense at the end and only at the end. Its middle expands on Gaspery’s life, taking him from a listless 20-something to a somewhat unconvincing new candidate at the Time Institute. We’re meant to believe Zoey uses her influence to get her brother the position, but it’s difficult to understand why he wants it so badly.

That’s a small quibble to make of a novel that is pure pleasure to read. “Sea of Tranquility” isn’t “Station Eleven.” It also isn’t “The Glass Hotel.” Mandel stans might already surmise that the Vincent named here is Vincent Alkaitis of “Hotel”; he and Mirella Kessler have roles to play, although the connection between the novels is more conceptual than narrative. That’s to the good because, in retrospect, “Hotel” feels like a step backward, “Tranquility” a giant leap.

After the initial trauma of lockdown, it seems Mandel has unlocked the sense of play and puzzle-making that shimmered in her earliest work (for example, the etymological fun in “Last Night in Montreal”). Following Gaspery as he travels across time may remind you of the best passages in Ben H. Winters’ work or, even better, Ursula K. Le Guin’s.

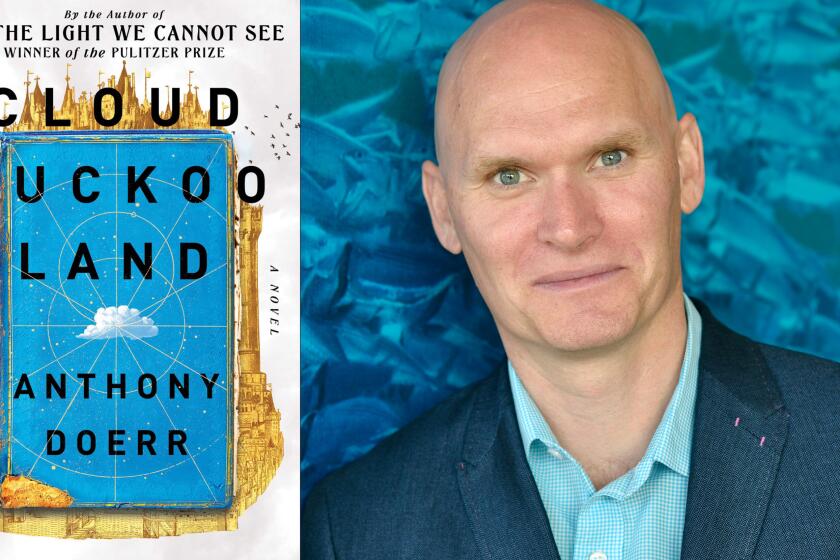

‘Cloud Cuckoo Land,’ Doerr’s followup to ‘All the Light We Cannot See,’ ambitiously maps a world connected by stories — if we know how to read them.

Yet, as in “Station Eleven,” Mandel is far more interested in human psychology than world-building. Witness Gaspery’s eventual undoing — where he winds up, what he does with his life. This brave new world is built on technology but still leaves room for old traditions — for violin lessons and, still more improbably, long attention spans. The Time Institute has its plans for humanity, but it hasn’t (yet) figured out how to control every individual psyche. People can still find wormholes with its wormholes to pursue their own ends — which can be as simple as helping a loved one or as complex as an ambition to save the world. If art is what survives in “Station Eleven,” here it is free will.

Of course, Mandel is too smart, and the rest of us too scarred by the past couple of years, to buy into any Utopia. She reserves her greatest scorn for the bureaucrats of the Time Institute. “What you have to understand is that bureaucracy is an organism,” Zoey tells Gaspery. “And the prime goal of every organism is self-protection. Bureaucracy exists to protect itself.” Is this a Canadian thing? (Mandel grew up in Quebec.) U.S. citizens have no love lost on bureaucrats, but they don’t generally hang the evils of the world on them.

Maybe we should. Mandel’s writing on bureaucracy recalls the functionaries in the movie “Brazil,” the dwarves of Gringotts in the “Harry Potter” series and the government employees in the TV series “Counterpart.” They’re competitive, malevolent and paranoid. One of the book’s last aha moments involves Gaspery realizing someone from the Time Institute has been manipulating Llewellyn all along — a dark but also funny comment on the machinations of modern book publishing.

Which returns us to Gaspery’s memory of the “Earth Ocean.” For all their water features, the colonies cannot replace the wonder of nature — the dark green forests and deep blue seas. More than one character has family “back on Earth”; Llewellyn’s parents chose to retire there.

Following a superb stylist like Mandel is like watching an expert lacemaker at work: You see the strands and later the beautiful results, but your eyes simply cannot follow what comes in between. As in her best work, including “Station Eleven,” she is less concerned with endings than with continuity. In “Sea of Tranquility,” her vision is not quite as bleak, but it is as strong — I won’t say prophetic — as ever.

Emily St. John Mandel, author of the pandemic bestseller “Station Eleven,” discusses her novels with the L.A. Times Book Club.

Patrick is a freelance critic who tweets @TheBookMaven.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.