- Share via

On the Shelf

Harry Crews, reissued

The Gospel Singer

Penguin: 224 pages, $17

A Childhood: The Biography of a Place

Penguin: 192 pages, $16

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“My uncle gave me a copy of ‘A Feast of Snakes’ in exchange for cleaning out his shed,” says S.A. Cosby, author of “Razorblade Tears,” remembering his first encounter with the late Southern author Harry Crews. The Tennessee writer Kevin Wilson happened upon Crews’ paperbacks while reading between classes in a Vanderbilt University English department office. The novelist Ryan Chapman picked up Crews when his now-wife declared “A Feast of Snakes” her favorite novel. Only later did she reassure him she didn’t share the cult author’s nihilistic take on true love.

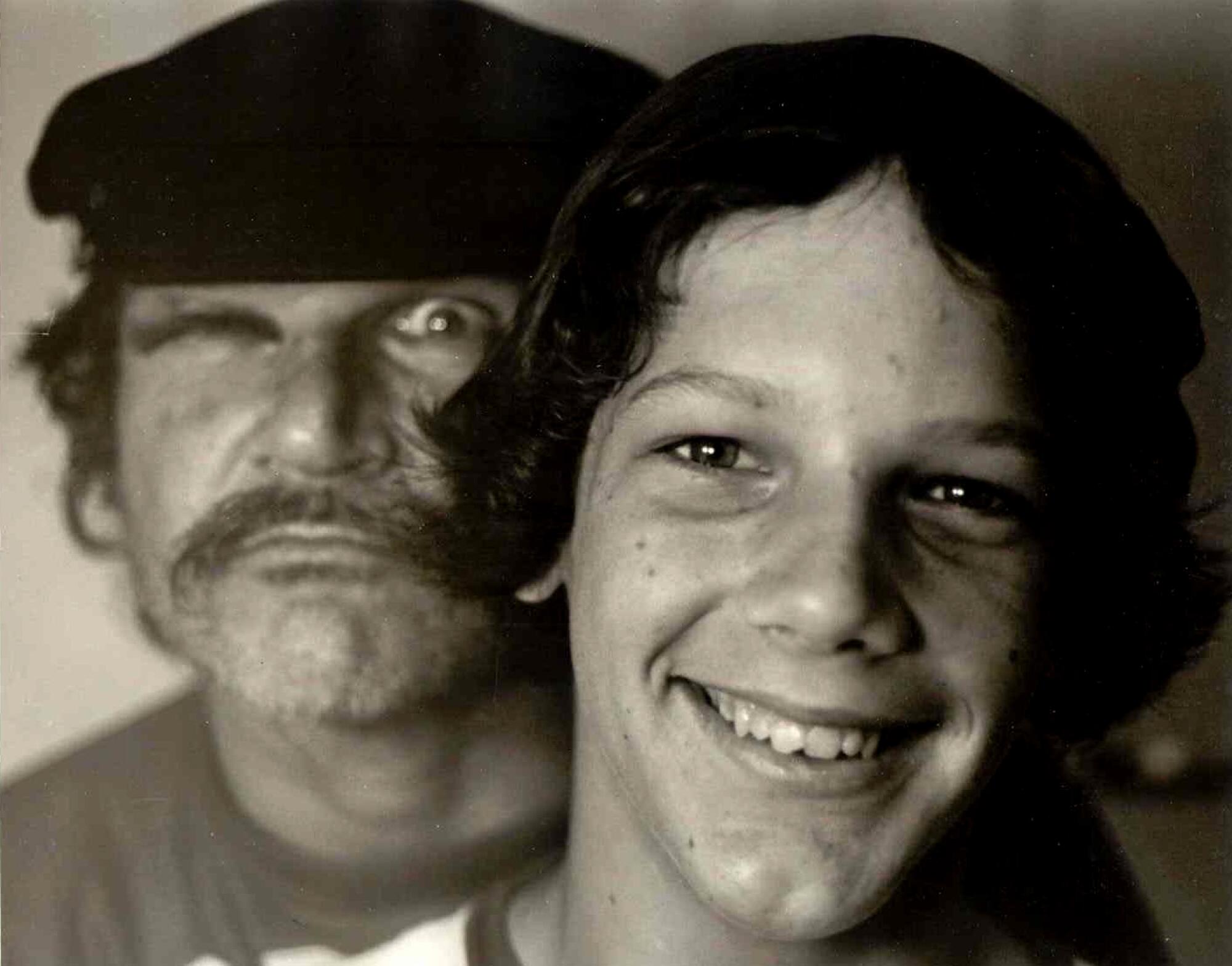

Critics and awards anoint some authors as legends. Others depend on word-of-mouth and prose that stands the test of time. “Art’s primary purpose was to offer up pleasure and crush the human heart with a living memory,” Byron Crews writes, of his father’s central focus, in an email. “Papa often judged writing by the degree to which it is honest and resonates and is memorable — across time — across years.”

This week, Penguin Classics will reissue Crews’ memoir “A Childhood: A Biography of a Place” (1978) and his debut novel, “The Gospel Singer” (1968). The imprint’s publisher and acquiring editor, Elda Rotor, recalled being “intrigued by his influence as an author and a teacher and curious about the craft of storytelling.” Struck by Crews’ “larger than life” mark on literature, she hopes the reissues will allow a new, wider readership to wrestle with his works and “revisit them through the lens of classics.”

For several years now, Penguin Classics has taken great pains to republish unsung works by marginalized authors. So what prompted them to revisit a straight, white male whose work is fraught with racism and a masculinity so toxic it sometime shoots past misogyny and straight into assault? The answer is as complicated as the man himself.

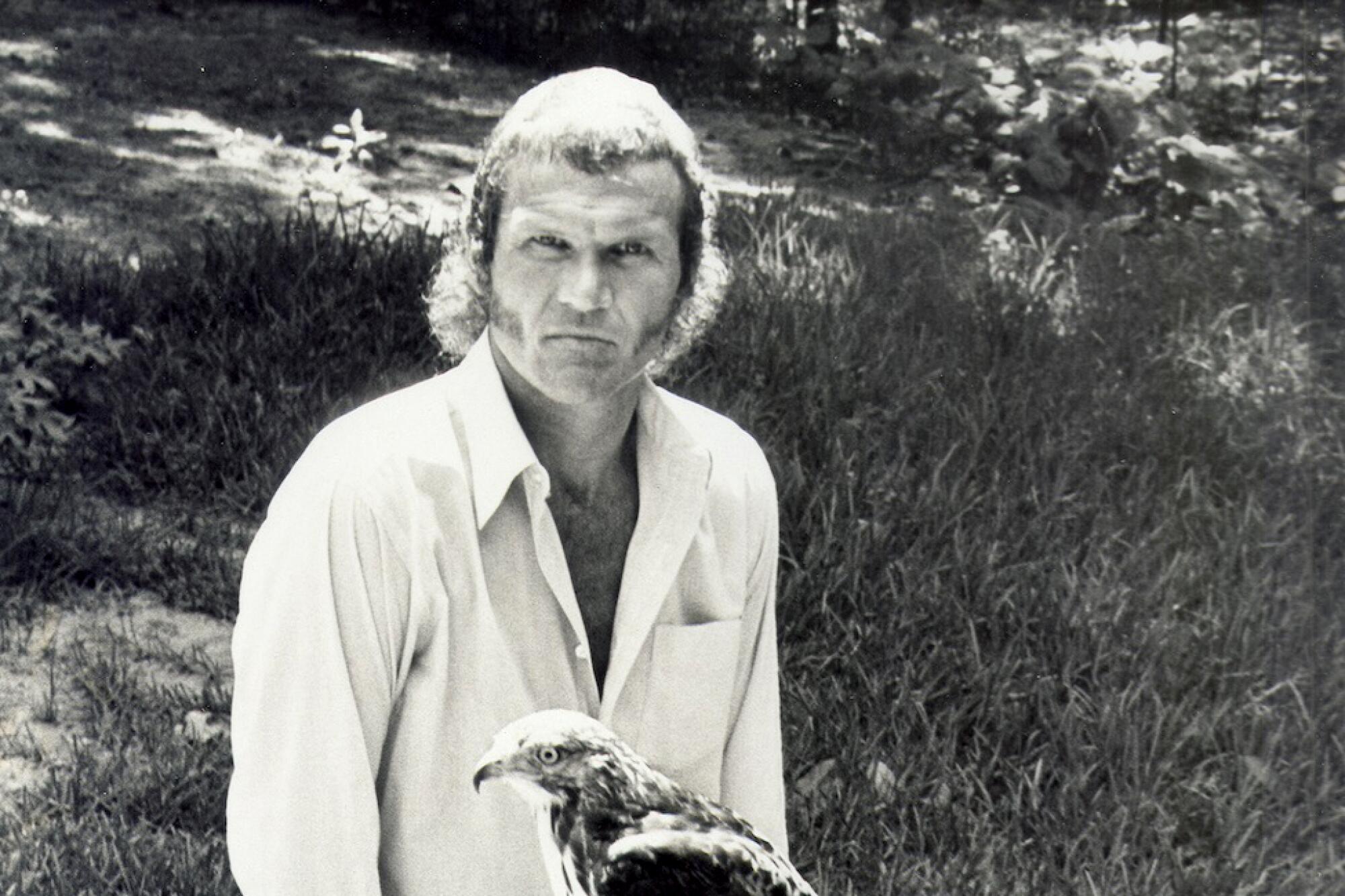

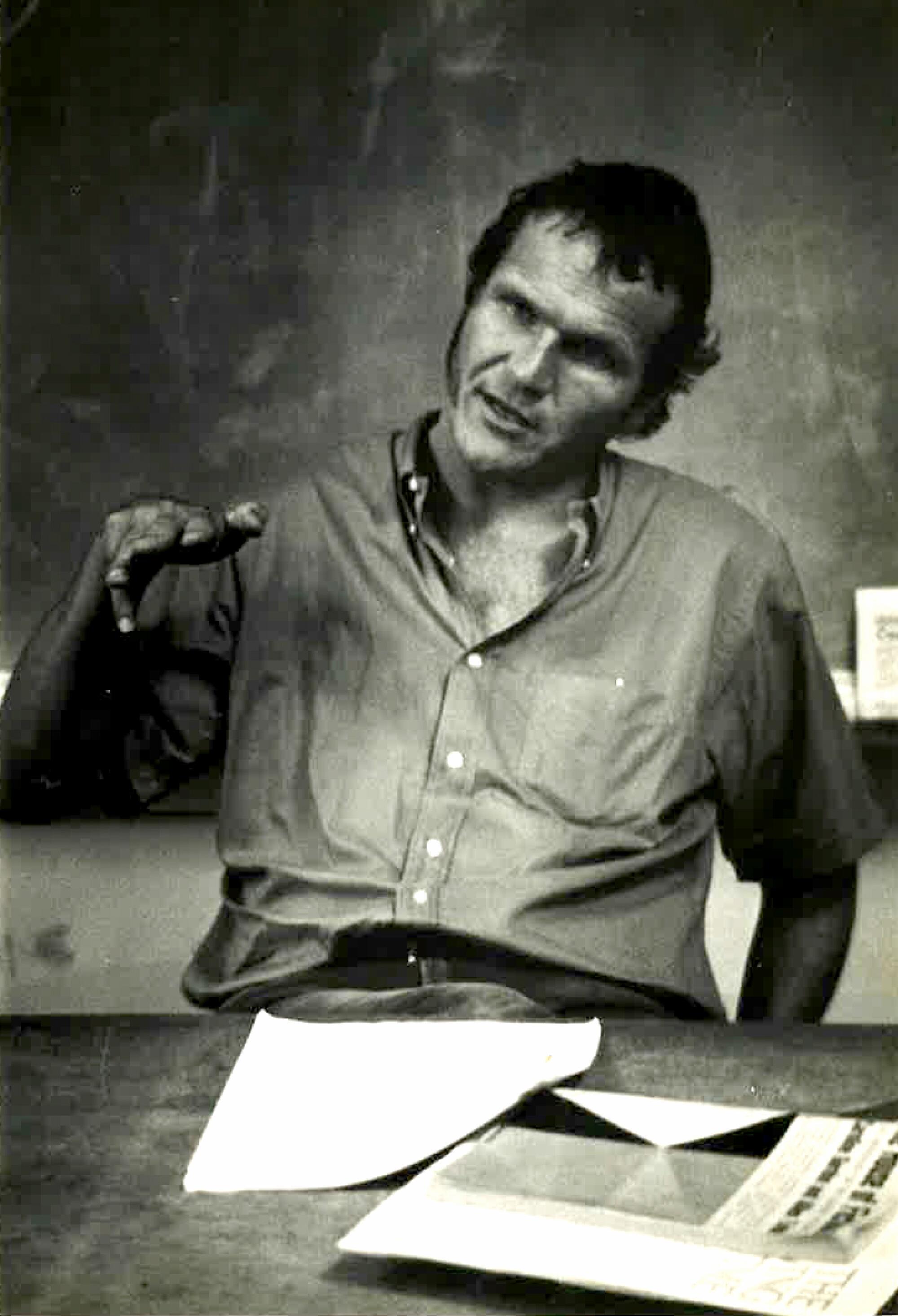

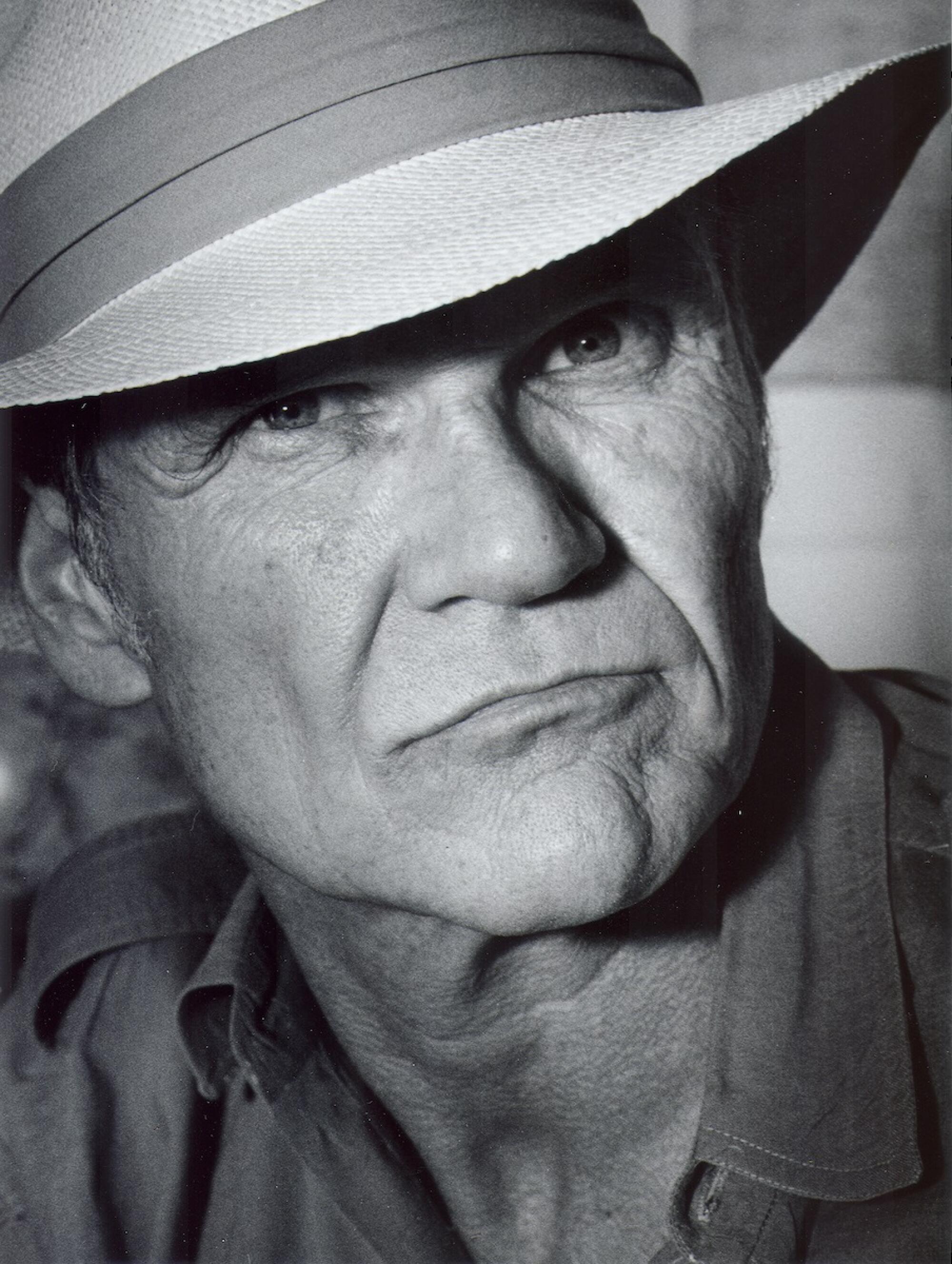

At times better known as a tattooed provocateur who sported a mohawk long into his later years, Crews was the strange and blistering author of 20-odd works. Between his birth into a Georgia sharecropping family in 1935 and his 2012 death in Florida as a retired professor and former Marine, he witnessed the South’s shift from a rural society to an increasingly industrial and cosmopolitan region marked by the civil rights movement and its backlash.

S.A. Cosby’s “Blacktop Wasteland” stakes out territory in undersung places — and sings too of the complex lives of Black men.

The conception of the typical Southern writer has evolved just as dramatically over those decades. The one constant across generations has been the paradoxical place of Southern lit: acknowledged as perhaps the most vibrant regional writing in the country yet often dismissed as too idiosyncratic to represent American literature at large. Its bestsellers, from “Where the Crawdads Sing” to John Grisham’s thrillers, are rarely associated with it; “Gone With the Wind” surely is, but it rang false when it was new.

Canonical midcentury Southern writers — Faulkner, O’Connor, Welty — were often perceived as white eccentric outsiders. Today the field reflects the diversity and modernity of the region (Jesmyn Ward, Tayari Jones, Kiese Laymon, Cosby and many others). They represent the whole of America — but then, so did their forbears, because, as Imani Perry recently argued, the South is America. It’s a farce to isolate racism, classism and misogyny past or present in one region.

Among those fighting back against such convenient parlor tales was Crews, whose work serves as a bridge between Southern writers past and present. Richard Howorth, the owner of storied Square Books in Oxford, Miss., notes that while Crews’ voice was “distinctly Southern,” he was also “unquestionably unaffected, genuine. There was no one like him at the time.”

There is nothing folksy, never mind pastoral or genteel, about Crews. With caustic and fabulist writing, he exhumed the ghosts of America’s original sin.

Crews’ memoir is studded with shocking events: After losing his father at age 2, he was raised as his uncle’s child until that uncle nearly murdered Crews’ mother; he survived untreated polio and an accidental toss into a vat of boiling water with a hog; he closes the book with an evangelical revival that inspires the disturbing sexual assault of another child.

This is an account of a life devoid of options or guideposts save for ritual and faith. His novels too are set in a lawless South, their characters so surreal and disturbed they could be found only in dead-end towns marked by dirt roads and moonshine. In “The Gospel Singer,” the title character returns to perform in his hometown just as his old acquaintance, the Black preacher Willalee, who shares a name with Crews’ childhood friend, is charged with the rape and murder of the singer’s childhood sweetheart. The singer is trailed, meanwhile, by a freak show the likes of which Katherine Dunn could not have imagined.

Wilson, a professor at Sewanee, wrote the introduction for “The Gospel Singer.” The novel is “horrific,” he notes in an interview — and yet “the sentences at times are just unbelievably beautiful.” Building on this contrast, Wilson debunks any rumor of sentimentality in the work: “Crews doesn’t have nuance regarding race or gender or religion or really anything, but the one place he is nuanced is his language.” By being “wildly precise and violent,” Crews’ style captures a society unsuccessfully struggling to move past its complicity in the horrors of slavery.

The author of “Nothing to See Here” enjoys BennY RevivaL, furniture-breaking wrestling moves and lots of books in his quarantine diary.

“You’re implicated every minute of your life here, right?” Wilson adds. “Like, if this is a broken place that’s haunted by the specter of all this violence and cruelty, then simply existing in it makes you culpable.” Even the shocking conclusion of “The Gospel Singer” leaves Wilson with the impression that “Crews isn’t necessarily making a commentary on race. To him, there’s just no escaping the cruelty and violence of this world.”

Cosby, a native and lifelong resident of Virginia, also expanded in an interview on his relationship to Crews’ work. “I grew up in a small town where there’s a giant Confederate statue in front of the courthouse that sends a message to you as a Black person,” he says. “Don’t look for redress of grievances. I always love reading his stuff, because, even if [Crews’] characters will embrace the Confederacy or the Lost Cause, he doesn’t embrace it. He ridicules it.”

For Crews, it’s ultimately bound up in class: Stoking racism distracts poor white folk from organizing against the elites. His bleak observations avoid judgment, yet the carnage in his writing speaks for itself. Without a moral reckoning, there isn’t enough money, drugs or religion to save a community from itself.

Cosby and Wilson spoke at length about how Crews exceeds even Faulkner and O’Connor in depicting a grotesque anti-pastoral that spares no one. “When I read him,” says Cosby, “I always felt like he was a person who realized racism, sexism, misogyny were all wrong, but instead of shying away from [these horrors],” Crews opts for “sensory overload.” He imagines Crews saying, “I’m not going to give you any moral proclamations. But I’m going to show you how bad it can get.”

Ultimately, the emotions and conflicts Crews depicted weren’t bound by geography. He wrote about nothing less than the starkest extremes of human nature.

In “A Childhood,” he asks who would tell his son about him. He surmises, “A few motorcycle riders, bartenders, editors, half-mad karateka, drunks, and writers. They are scattered all over the country, but even if he could find them, they could speak to him with no shared voice. … For half my life I have been in the university, but never of it. Never of anywhere really. Except the place I left, and that of necessity only in memory.” He concludes the thought by explaining why he turned to memoir. “Only the use of I, lovely and terrifying word, would get me to the place where I need to go.”

The writer and Princeton scholar on “South to America,” her personal and historical tour of the region, and why so many liberals are wrong about it.

Self-deprecation aside, Crews captured the raw essence of humanity in both fiction and nonfiction. Side by side, these reissues form the complete picture of an imperfect man who charged hard into extremes to escape his cultural inheritance. Leaving the South was no answer; his demons belong to all of us. His journey was a nightmare we must all face before waking.

LeBlanc is a book columnist for the Observer. She lives in Chapel Hill, N.C.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.