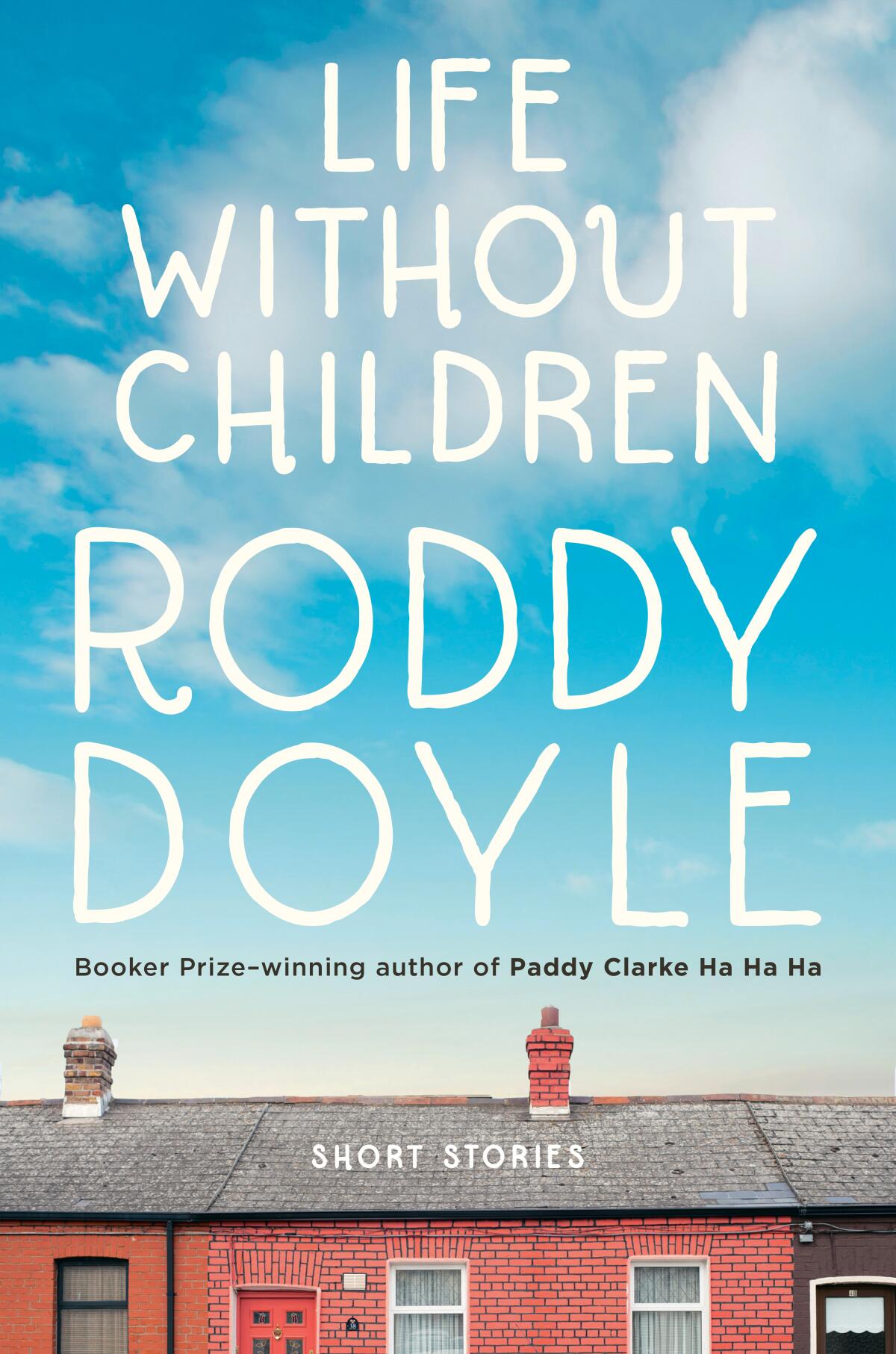

Roddy Doyle’s hapless Irish men find COVID a formidable foe in his new story collection

- Share via

On the Shelf

'Life Without Children'

By Roddy Doyle

Viking: 192 pages, $25

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Novels about the pandemic are starting to roll in, including “Our Country Friends” by Gary Shteyngart, “The Sentence” by Louise Erdrich and “Summer” by Ali Smith. There will, no doubt, be many more in the years to come. Their slow arrival may have less to do with lack of material than with the publishing industry’s resistance to forms that might better suit it. Roddy Doyle’s new collection, “Life Without Children,” provides evidence that the short story, with its contained scope and drive, is the best way to convey how intensely individuals have struggled with COVID-19 and its global ramifications.

Another habit of Doyle’s that runs counter to publishing trends: He is a defiantly regional writer, his region being Dublin, Ireland. His best-known novels, including the Booker Prize-winning “Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha,” are rife with Irish syntax, slang and shorthand. But something more universal in his style, its claustrophobic force and mastery of close-quarters dialogue, works especially well in a volume all about the lockdown — like Bo Burnham’s “Inside,” except these characters have always been inside. They aren’t going anywhere, and you know the feeling. You’re going into their heads, and it’s going to be uncomfortable and unsettling, even upsetting.

Uncomfortable, for one thing, because most of Doyle’s talkers are men in late midlife, men whose children have grown up, left home and sometimes left off communicating. Doyle does set one story in the consciousness of an exhausted woman, a nurse who arrives home after a day when two patients die, and another story, “Gone,” revolves around a man’s worries over his virus-stricken wife. But these pieces are largely windows into the fears of aging men who find their 20th century worldviews dangerously out of fashion.

Over lunch and cocktails, the satirical and melancholy novelist unpacks his raucous new Hudson Valley pandemic-era novel, “Our Country Friends.”

Very few modern fiction writers can do so much with so little. Doyle has been honing his ability for a long time, and his genius springs from scarcity as a catalyst. Find yourself jobless? Buy a food truck (“The Chipper”). Need a creative outlet? Start a band (“The Commitments”). Accidentally pregnant? Refuse to leave home (“The Snapper”). When all else fails, have a conversation down the pub. Doyle has posted snippets of such chats on his Facebook page, and his 2020 novel “Love” consists largely of friends Joe and Davy in an epic barroom dialogue.

In “Life Without Children,” Doyle’s repartee emerges in more varied settings and more structured stories. The blarney is still strong here (lapsing into Irish dialect is an occupational hazard of reading him), but these characters also act. Situations once familiar and sufficient to his plots — broken curfews, lost jobs — are now attached to an unstoppable contagion and its unaccountable losses.

In “Box Sets,” Sam feels ready to hunker down at home with familiar cookbooks and 30 years of boxed TV dramas, but he may have gotten so comfortable inside that he’s pushed his wife out the door. In “The Five Lamps,” a man whose son left home searches the too-quiet Dublin streets during isolation, hoping that someone — anyone — can tell him of his adult child’s whereabouts.

As they fumble with cleaning products, medication schedules and hospital visits, Doyle’s men have to learn new tricks — not just novel household tasks but ways of reaching outside themselves. For some of them, decades flew past while they did the same kind of work in factories and offices, leaving the child-rearing to wives and other female relations. Now they start to realize, blinking like newborns, that it wasn’t just the children the women took care of: It was also them. If, in the title story, Alan thinks he “wasn’t needed anymore,” maybe that’s just what he requires to find real purpose.

In summer 1991, a small movie about a group of young Dubliners who form a band to play American soul music opened with little fanfare.

Doyle fans already know he’s too sly to maintain such earnestness for long, and even mopey Alan manages some droll asides. On a business trip to Newcastle, he hears some women “on a hen do” (bachelorette party) shouting, “Tracey wants some cock!” and muses: “The droplets they’ll inhale tonight, they’ll be dead in days. Here lies Tracey. She wanted some cock.”

The Doyle-ean subtext is: Of course she did. Everyone wants something badly, even (or especially) if they can’t get it because of face masks or vaccine protocols or death. Substitute “a box set” or “a takeaway” or “a chocolate mud cake.” “We need the oul’ treats,” says one man to another — and you remember that everyone has desires, as small as a pastry or as large as a reunion. In “The Five Lamps,” the collection’s final story, when the desperate father finds his boy, he hands him a plastic bottle of mango smoothie, a transactional moment that stands in for a transcendent impulse to connect.

Doyle, born in 1958, has seen gains and losses in his native Ireland and around the world. He is the right writer for this job because he can take a worldwide event and distill it into a delicious fruit drink or a pint of properly pulled stout — if not a world in a glass then at least a full experience. Like the privation that fueled his earlier plots, global disaster doesn’t necessarily bring out our best selves, or even different ones. But it reveals a lot, and it makes for a tasty batch of stories.

Sometimes a man doesn’t rise to the occasion. But once in a while he can, as in “Gone,” in which decades of marital indifference give way to love, even if it’s too late — his wife is gravely ill with COVID. Doyle does tell us whether she lives or dies, but it’s immaterial. The important thing is that he wakes up to what’s in front of him. “Life Without Children” immerses readers in the pandemic but reminds them that the only things that matter are those that we always have, even if we didn’t know it.

Bethanne Patrick’s February picks include two Nobel Prize winners, tales of Hollywood then and now, a new African fantasy epic and much more.

Patrick is a freelance critic who tweets @TheBookMaven.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.