Sex writing as literary parlor game? Why 27 writers decided to bare (almost) all

- Share via

On the Shelf

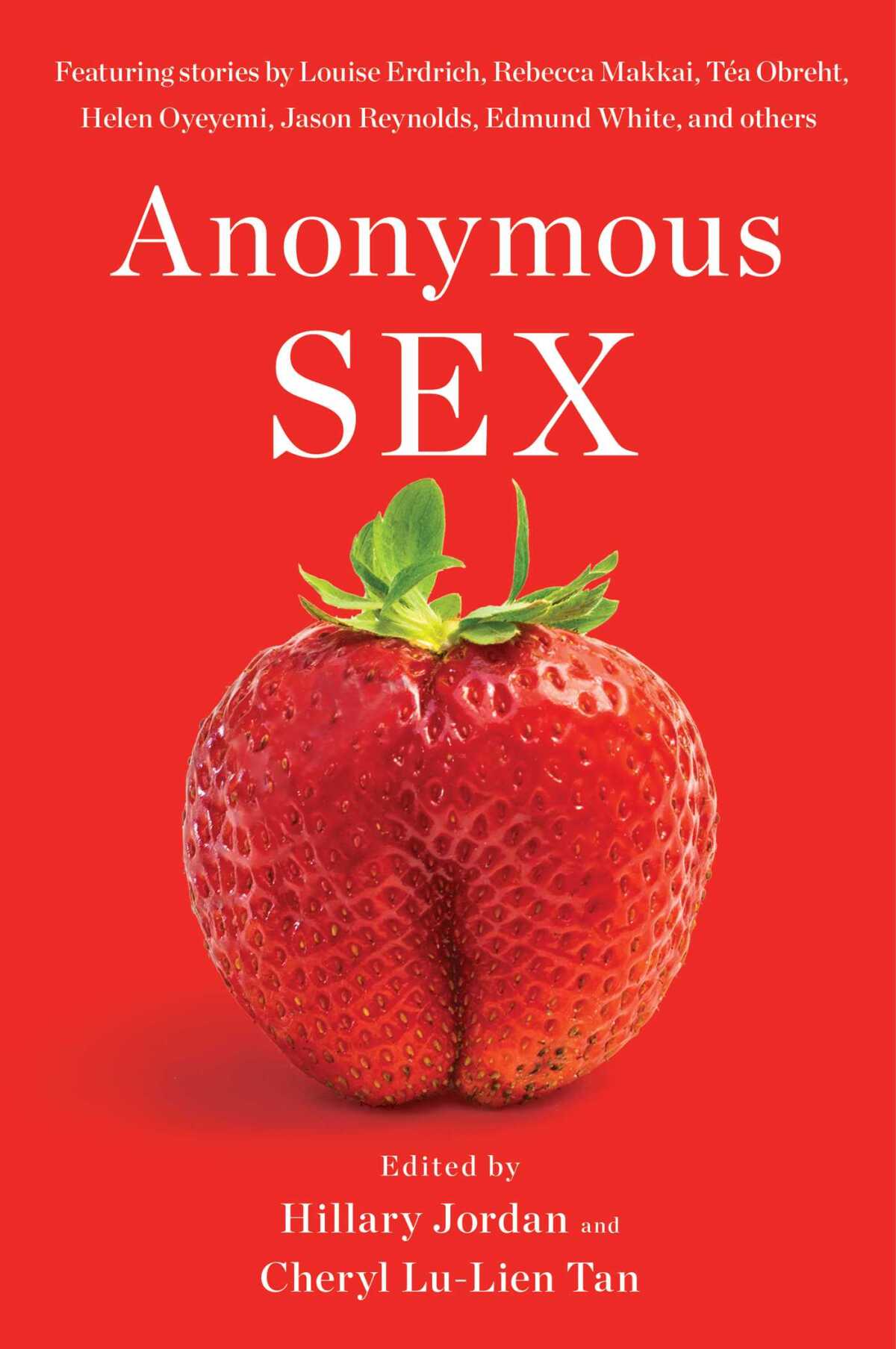

Anonymous Sex

Edited by Hillary Jordan and Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

Scribner: 368 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“27 Authors. 27 Stories. No Names Attached. A bold collection of stories about sex that leaves readers guessing who wrote what.”

So reads the jacket of “Anonymous Sex,” whose title is a bit of misdirection. This collection of erotic short stories is not about anonymous sex. It’s not even about sex. It is sex, largely of the kinky, heterosexual variety, artfully composed. And its authors include some household names. As contributor Luis Alberto Urrea told me, “Every story in this book was written at the top of each writer’s game.”

Clamps, slaps, rolled-up magazines and nimble fingers fill these pages, which engage the upper as well as the lower chakras with stories about long-distance seduction, best-friend seduction, seduction in a Brooklyn Book Festival bathroom, seduction while skinny dipping and cyber-seduction in the year 2098, all wrapped in polished prose. “Anonymous Sex” offers an unbeatable match of writer and subject. Probably.

That’s the anonymous part: A list of author names is provided but unattributed, and the reader is invited to guess which author wrote which piece. Some readers — especially the few who have read the authors’ other work closely enough to recognize their voices — will experience this challenge as a two-fer: a parlor game within a sizzling assemblage of top-notch literary fiction. Others might see the anonymity rule as promulgating the very sexual shaming it purports to remedy, a fig leaf shielding writers’ reputations from the consequences, real or imagined, of publishing their sexual imaginings under their own names.

Are we really there? In 2022? Novelists concerned that their careers will be sullied by publishing their own made-up smut? If so, why would the editors solicit writers who require anonymity when there are so many wonderful authors happy to own their sexual stories — including, as we shall see, some contributors to this book?

Seeking answers, I consulted the anthology’s co-editors: Hillary Jordan, author of the bestseller-turned-movie “Mudbound,” and Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan, author of the novel “Sarong Party Girls,” along with contributors ranging from two-time Booker Prize nominee Chigozie Obioma to Emmy winner (and memoirist) Mary-Louise Parker. (Others include Helen Oyeyemi, Rebecca Makkai, Louise Erdrich and Edmund White.)

Tan and Jordan conceived and edited “Anonymous Sex” while they were 9,000 miles apart — quarantined in New York City and Singapore, respectively. Tan explained that their approach was, in part, a way of prompting (or skirting) the modern question of cultural appropriation. “At a time when the literary and artistic world is debating who has the right to write which story, it was interesting to tell our authors, ‘You can write anything you want,’” Tan said. “So readers won’t experience each story through the narrow lens of ‘This was written by a female, trans, gay or cis male writer in India or Nebraska.’”

Among winners of the 2021 Pulitzer Prizes are novelist Louise Erdrich, Malcolm X biographer Tamara Payne and the post-Reconstruction history “Wilmington’s Lie.”

And then there were the practicalities. “I have zero worries about being seen as someone who writes about sex, but some of our authors shared that they were able to write more freely because their names were attached to the book, but not to their own stories,” Tan said.

“I’d say at least half of our authors wouldn’t have agreed to be part of the project without anonymity,” Jordan added. “We all signed contracts agreeing not to reveal which story we wrote for a year and a half after the pub date. At that point, the rights revert to us and we can tell if we wish, but I’m hoping everyone takes it to the grave. I certainly plan to!”

I asked a few of the authors what made them semi-willing to semi-reveal sexual fantasies that might or might not be their own, and whether anonymity was an enticement.

“I’m not a prude, at least not as a writer. I didn’t write anything here that I wouldn’t write with my name attached,” said Obioma. “People will always make wrong-headed judgments about writers. And keen readers might be able to still tell who wrote what if they read closely.”

Urrea agreed: “It’s not truly anonymous. My readers will know my story, I think. I just wrote maybe a half-click more explicitly than I would have in my own work. The ‘anonymity’ is not the writers hiding from what they’ve written, but writers playing with the audacity of the editors’ vision.”

Heidi Durrow, an acclaimed novelist, found that “the anonymity was a plus. Although my novel [“The Girl Who Fell From the Sky”] has been banned by school libraries and school districts, so it seems some people maybe think I’m already writing in this genre. The anonymity is part of the titillation for the reader, I hope. I know people will try to guess, but I’m not telling.”

Téa Obreht, the Serbian American novelist who won the prestigious Orange Prize in 2011 for “The Tiger’s Wife,” also sees the undercover approach as a good thing, but for different reasons. “I would have happily contributed to this anthology under my own name, but I did find the prospect of anonymity thrilling,” she said. “The book is a kind of literary masquerade ball. There’s something delightful about being invited to guess who is behind each mask. And though I expect my story to be linked to me eventually, I saw the preservation of my anonymity as both a mandate and a craft challenge. It made me pay particularly close attention to aesthetic decisions and tendencies by which I might be easily recognized.”

Conservative parents in Texas and around the country rally to expunge certain titles from school libraries for reasons of race and sex.

Parker, the actor, had strong words for writers who consider their reputations when deciding what to write (although her contribution to “Anonymous Sex” dwells inside the cone of silence). “When you worry about diminishing or enhancing your ‘brand,’ — sorry, that word makes me throw up in my mouth — you stop being an artist and become a salesperson,” Parker said. “Nothing wrong with being a salesperson, but that’s something to think about after creating something, not during or before.”

Surely these successful writers field all sorts of intriguing and lucrative offers. Why, I wondered, did they sign on to an erotica project that cloaks their credits? Several of them mentioned the fun factor, and the challenges: writing short fiction instead of novels, writing alongside stellar peers, writing about sex. “My wife made me do it,” confessed Urrea. “She said she wanted me to try something new. I suspect she was amused by my discomfort.”

Parker found meaning in the book’s sex-positive message. “Anything that makes people rethink their preconceptions is powerful,” she said. “At the moment there is very little, if any, gray area in regard to sex. Kids are having less sex because they are afraid to touch each other without consent. With young people, more sex happens on phones than with another person. Most kids have seen pornography by 10 or 11. The FBI says there are around half a million online predators searching for kids every day, but we hand our kids phones while censoring their libraries. I think we should be actively putting erotic literature in school libraries.”

Co-editor Jordan believes the book’s potential reaches beyond its sticky pages. “This country was founded by puritans, and many of those repressive attitudes linger on,” she says. “Women are often condemned for being openly sexual. I hope the book moves the needle away from the idea of shame and toward acceptance of sex in all its diversity.”

Several contributors found sex writing perfectly aligned with their more socially engaged writing. Obreht isn’t sure she sees the divide between erotic fiction and writing about, say, the traumas of the Balkan wars — or, for that matter, between sex and society. “Sex obviously intersects in endless ways with the most pressing social and political issues of our day,” she said. “It’s hard to imagine social progress without the ongoing effort to destigmatize sex and sexuality.”

Garth Greenwell spoke with me from Iowa City, where he’s bracing for the release of his already widely praised first novel, “What Belongs To You” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux: 208 pp., $23).

For Durrow, crafting steamy passages during the current political morass felt like a refuge. “The last few years have been challenging for me as a writer because I felt like my imagination was caught up in a cycle of outrage or despair with never-ending news stories of corruption, racial injustice, mass death, and the slow death of democracy,” she said. “The anthology gave us writers (and ultimately our readers) a chance to access another part of our imaginations. I hope this book brings some joy. We are all due some joy after these last few years.”

Humans may not be the only creatures who have sex, but few would argue with the notion that good sex — and good writing about good sex — expresses and deepens our humanity. “This is a humanist book about our contact and care for each other,” said Urrea. “Eroticism is part of that, and it is a necessary part of literature. I wouldn’t have participated if the book only represented one expected vision. It’s important to me that the contributors represent everything that we are and dream of being.”

If “Anonymous Sex” generates enough attention to serve Urrea’s ideal, that would far outweigh the potential harm of implying it’s too shameful to put one’s name on. Perhaps its sensual union of form and content can help usher in a culture in which a writer’s erotic imagination is celebrated — and proudly named.

Maran is the author of a dozen books and a frequent contributor to The Times, among other venues.

Changes in TV, film and book publishing, including the pandemic, have driven a boom in book adaptations. Here’s a guide to the pipeline.

A virtual launch for “Anonymous Sex,” sponsored by the Ripped Bodice bookstore in Culver City, will feature Heidi Durrow, Jamie Ford and Valerie Martin in conversation with the co-editors on Feb. 1.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.