- Share via

On the Shelf

Ulysses: An Illustrated Edition

By James Joyce, illus. by Eduardo Arroyo

Other Press: 720 pages, $75

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

James Joyce’s landmark modernist novel “Ulysses” turns 100 this year. The occasion will be marked by readings, discussions and a Bloomsday that blossoms like none before (on June 16, the day of Leopold Bloom’s peregrinations). Taking precedence over encomiums and recitations, costumes and nostalgia is the book itself, 710 pages of inner monologue and dialogue, stream of consciousness, blank verse, Greek classics and the venues and byways of Dublin, 1904.

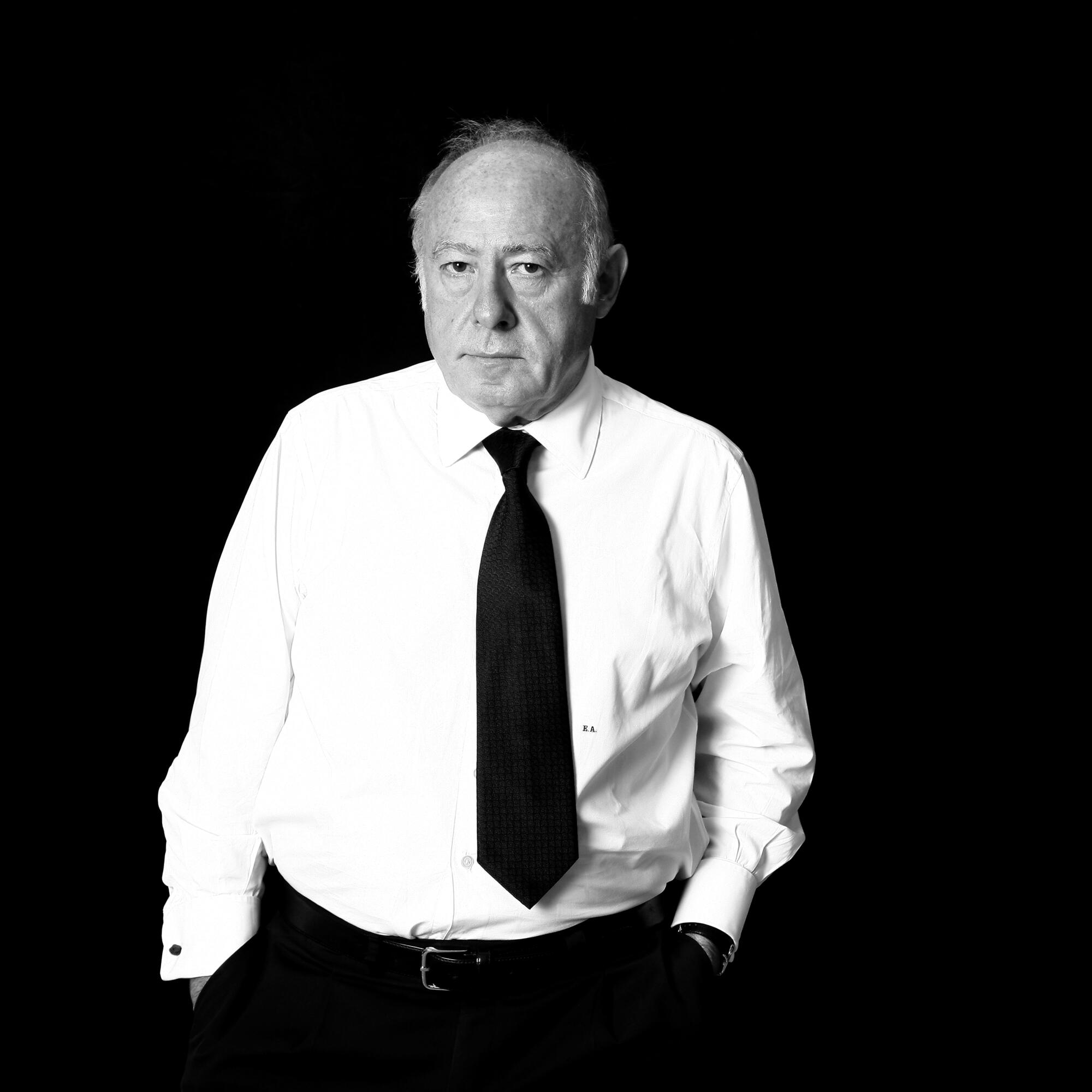

Other Press’ centennial edition, weighing in at 6 pounds, is likely to cut off the circulation in your thighs and force a skipped meal (at $75), but worth it for the extras. “Ulysses: An Illustrated Edition” includes 134 color illustrations and nearly 200 in black and white by Spanish artist Eduardo Arroyo, his final project before his death in October 2018.

“In 2004, we had been working on the first five books of the Bible,” recalls Joan Tarrida of Galaxia Gutenberg, who had collaborated with the artist since the 1980s. “And then Eduardo was always talking about, ‘my ideal, the dream project would be Ulysses.’” Arroyo suffered for decades from peritonitis, and “working on ‘Ulysses’ gave him the strength to survive. This ‘Ulysses’ has been a project for a long time.”

Three months before Arroyo’s death, Judith Gurewich, publisher of the independent Other Press, was in Spain meeting with colleagues. Arriving early for a visit with Tarrida in his Barcelona home, she waited in his office and found herself surrounded by Arroyo’s exquisite renderings, some framed on the walls and others lying on the sofa and chairs.

“There must have been 30 or 40 of these drawings or paintings that are now in the book,” Gurewich says. “Joan arrived, and I didn’t even say hello. I said, ‘What is that?’ We started talking about it and I said, ‘You think we can do this together?’”

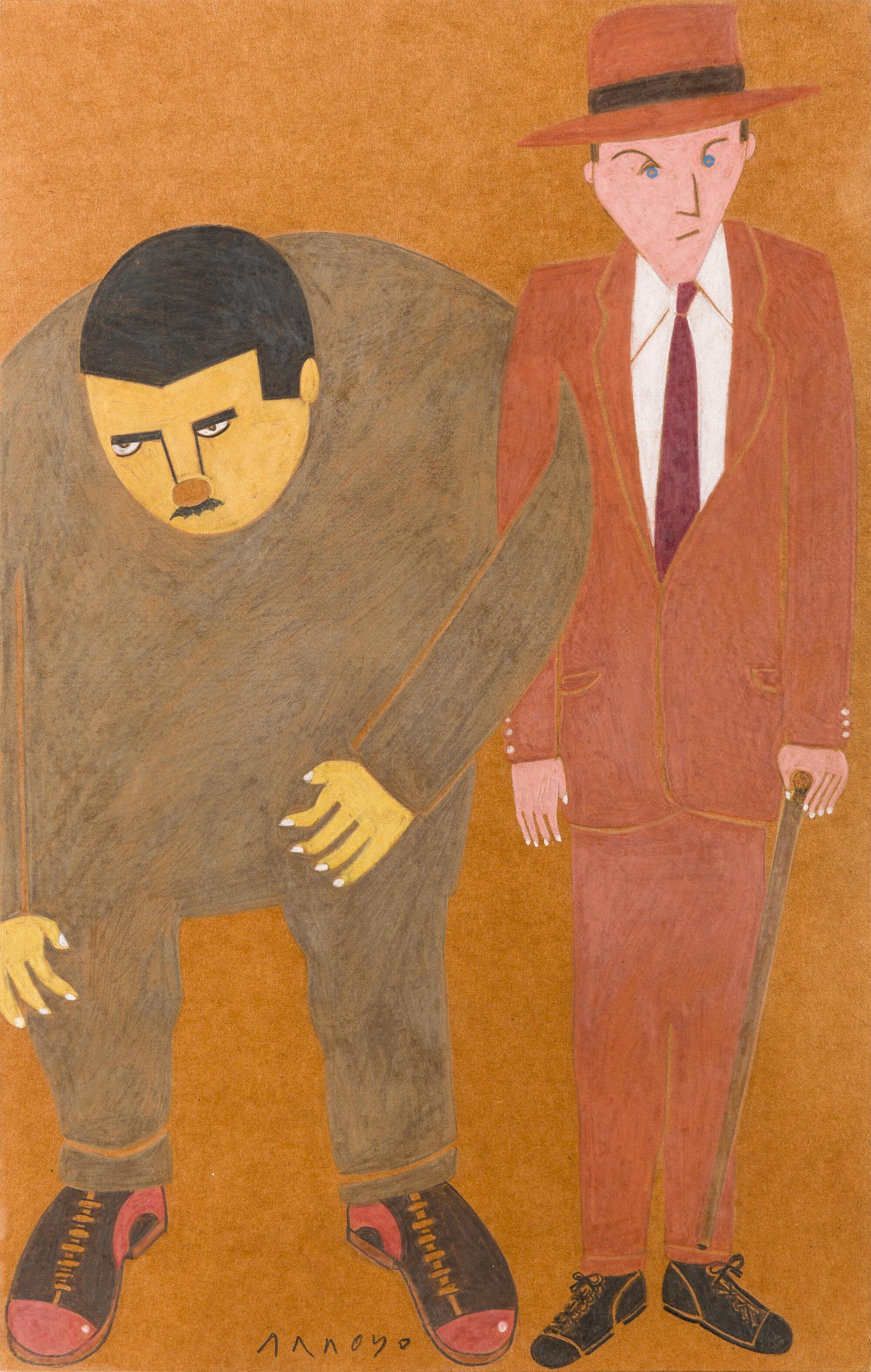

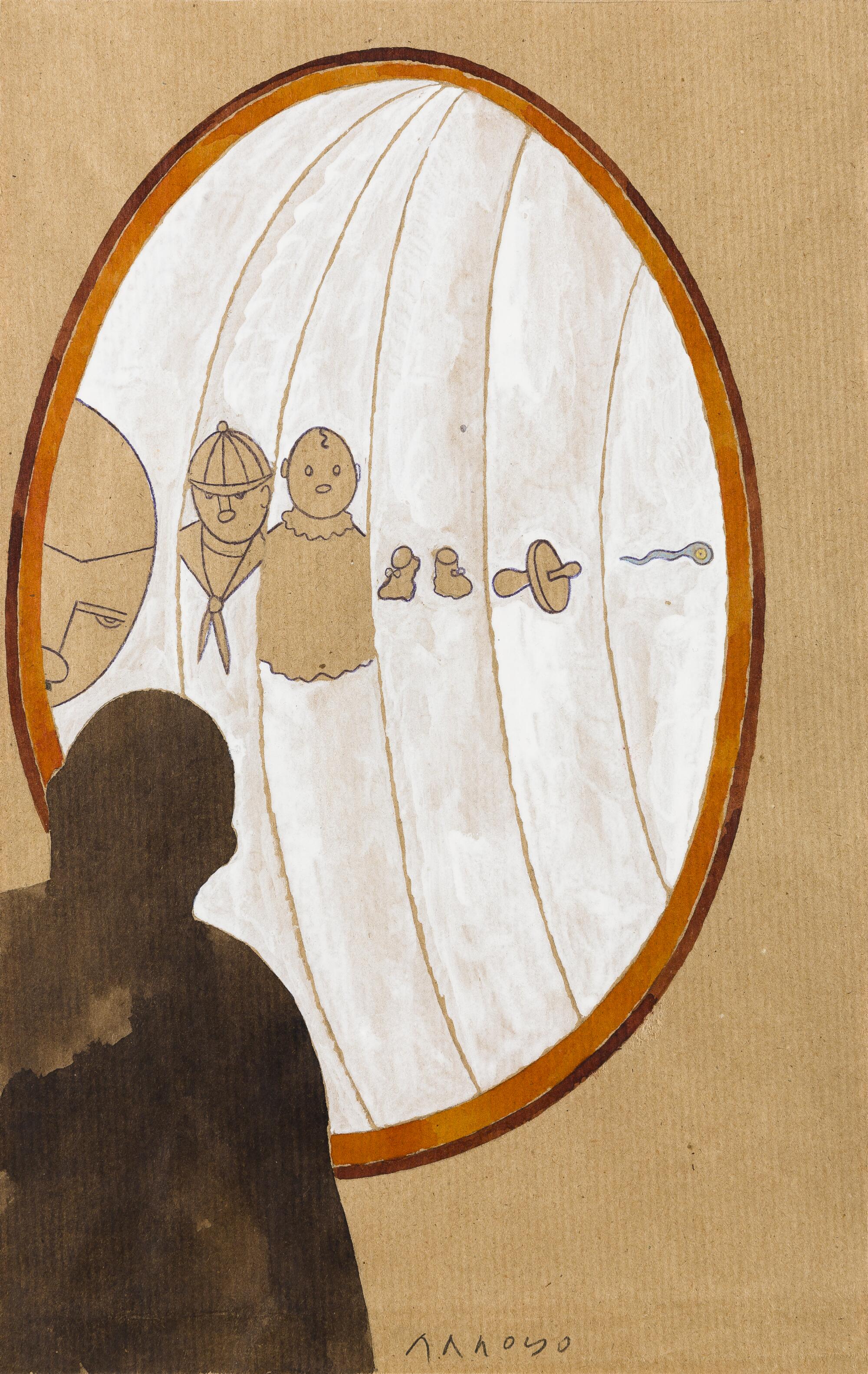

Arroyo’s playful, colorful works share a palette with the Pop Art prevalent in the 1960s, when he began to show mainly in Paris. His work was first shown in the US in 1975 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Madrid’s contemporary art museum has him in their permanent collection, as does the Institut Valencià d’Art Modern. His formats run the gamut — paper collage, chalk, ink, watercolor and graphite. Images are flattened out, replacing depth with collage-like layers, as seen in the cover portrait of Joyce, a study in green and beige.

The effect — of richness within simplicity — suits “Ulysses,” the formidably complex account of a simple advertising agent on his daily routine in Dublin. The narrative occasionally shifts to Bloom’s unfaithful wife, Molly, or an acquaintance, Stephen Dedalus, a writer spun off from Joyce’s autobiographical “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.” Nothing much happens to Bloom in the course of the novel — he goes to the butcher shop, a burial, has a bowel movement and later masturbates on the beach.

Maps illustrating the terrain of Joyce’s ‘Ulysses,’ ‘Game of Thrones,’ Raymond Chandler’s L.A. and much more are on display at the Huntington Library.

The seeming randomness of events, along with the free-flowing style (one of the first uses of stream of consciousness), belies a structure that is literally classical — employing its source, Homer’s “Odyssey,” as a heroic template applied to a humdrum Irishman, and thereby bringing the epic into the everyday, poetry into prose. Obscurantist and yet earthy enough to have been deemed obscene, it has become a cultural touchstone without getting any easier to read.

“I remember the first time we read ‘Ulysses,’ it was like it was Shakespeare, and we had to understand the cadence and nuance, and that became tortuous,” novelist Adrian McKinty recalls of encountering the novel as a student. He grew up in Belfast before becoming a bestselling author (from “The Chain” to the upcoming “The Island”). “To understand this book, I have to understand who clerics were in the 1890s?! To me, that’s a failure of communication on the part of the novelist. Bloody hell!”

His second time reading it, however, McKinty breezed through, caught up in the transcendent verbal embroidery, missing dozens of references but picking up on others. “Exactly as the reader would want to do it, spend a year and go a page a day or fly through it and go 40 pages a day and miss most of the references. Either way is perfectly acceptable.”

“Ulysses” was hardly written for modern attention spans, and Arroyo’s images provide a welcome respite in the Other Press edition. When Buck Mulligan requests Dedalus’ handkerchief to wipe his razor clean, the artist gives us a two-page cutout collage of a black sleeve pulling a stained white rag from a pocket. The reference to their roommate’s dream of a black panther is portrayed in a black-and-white doodle of a gun, the smoke from its barrel morphing into a cat with a human face — Joyce’s slippery surrealism fleshed out.

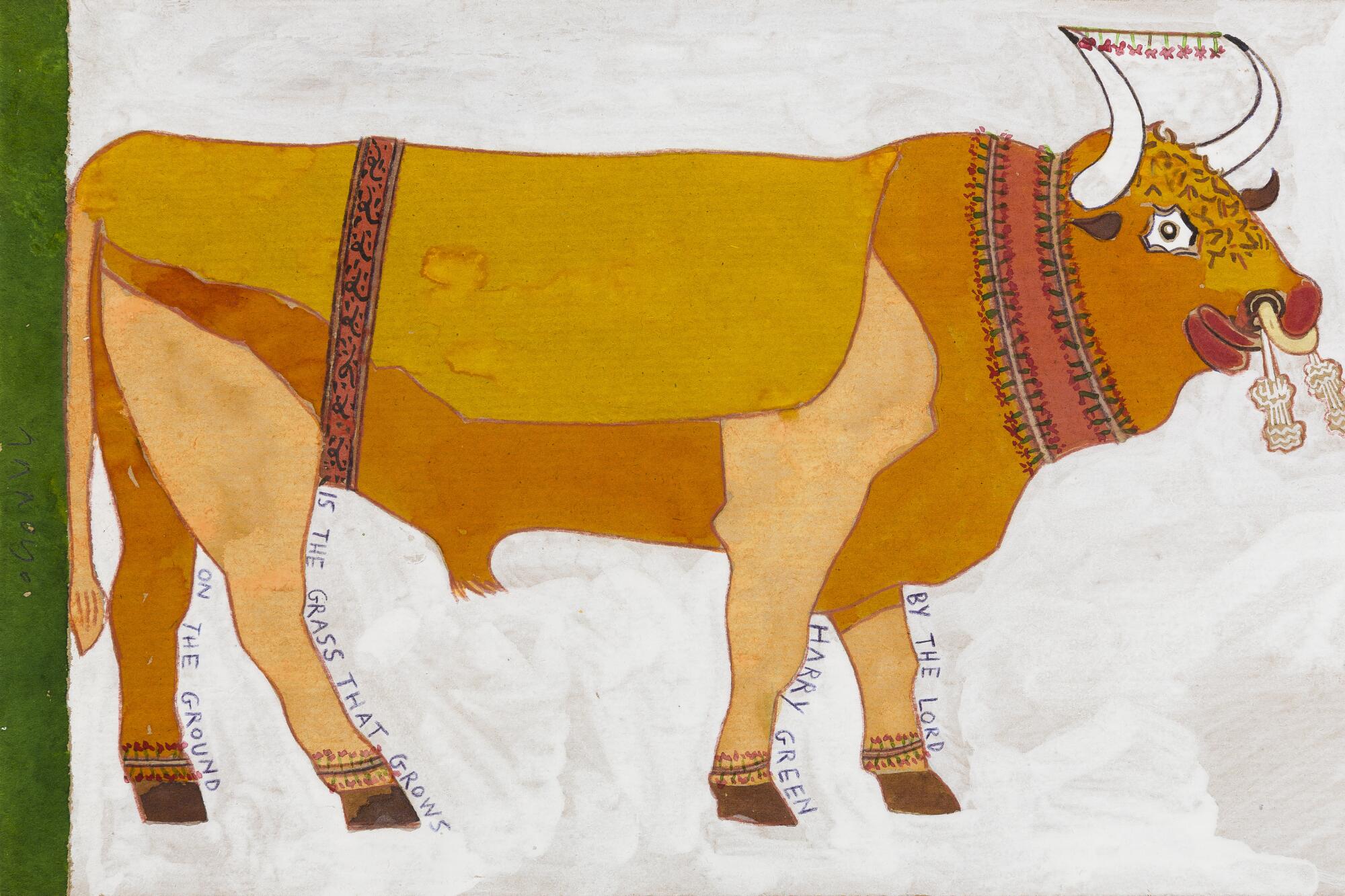

Of course there are graphic nudes, especially in later chapters — a penis writes the words “wet dream” — but also more abstract treatments of sex; bats and fireworks, motifs taken from the text, illustrate Bloom’s climax on the beach. And there are classical references mirroring Joyce’s, such as the full-page painting of a bull in the style of the ancients to illustrate a passage about a renowned bovine stud.

The literary holiday June 16 celebrates James Joyce’s great conflation of life and art “Ulysses.” This year the global revels — virtual, for the most part — will be more the latter than the former.

An image accompanying Bloom in the maternity ward animates the progression from sperm cell to pacifier, booties, baby, boy and man — a kind of temporal compression within a single frame that is hardly unique to graphic novels. Tarrida considers it an homage to Italian Renaissance masters who did much the same thing. “He’s using many different ways of painting,” Tarrida says. That may be a reflection of the many years Arroyo spent crafting the images.

Joyce’s own eclectic masterpiece came together fairly quickly, but its road to publication was famously bumpy. It began as a short story in his 1914 collection “Dubliners” and was largely written as the author sat out World War I in Zurich. Completed around 1920, “Ulysses” was serialized in journals both in England and the U.S. — the latter resulting in a trial under the Comstock Act. It wasn’t until the mid-1930s that both countries deemed the novel publishable. Its notoriety thus preceded its publication by a decade.

“If it had come out and there was no scandal, I don’t think it would have been as successful as it is,” says McKinty. Joyce’s response to his critics was, “If ‘Ulysses’ isn’t fit to read, then life isn’t fit to live.” He died in 1941, two years after the publication of his even more abstract epic, “Finnegans Wake.”

Arroyo never got to see his illustrated masterpiece; he died only a few months after Other Press initiated the project. He did manage to see the first 200 pages on his deathbed.

“It was fantastic just because I had the time to tell him that the book would be published, the English version. For him, that was paradise,” recalls Tarrida. “For him, it was a dream coming true; in his last moments, he knew ‘Ulysses’ would be published.”

In ‘Seek You,’ Kristen Radtke melds social science and personal anecdotes with hauntingly beautiful imagery, making the lonely feel less alone.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.