A young writer’s road to sobriety and an addiction novel that redeems the genre

- Share via

On the Shelf

'All Day Is a Long Time'

By David Sanchez

Harper: 256 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

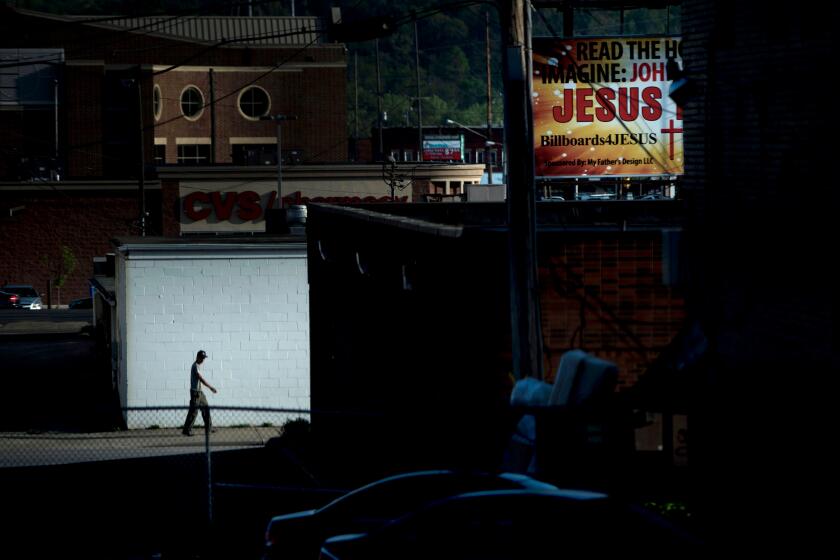

Sitting in front of his screen, grasping for an idea for a class assignment in December 2017, David Sanchez appeared to be just another M.F.A. student at the University of Miami. He had entered the program with a typically simple but ambitious goal: “I wanted to leave there with a novel and an agent.”

Noticing how his cigarette was drying out his mouth, he started thinking about how meth makes the saliva “disappear from your mouth,” which is what rots an addict’s teeth. “I wrote that down, and it started coming to me,” he recalled recently, cloaked under a hoodie, via video while discussing his first novel, “All Day Is a Long Time.”

Sanchez had begun typing that day, fast and furious, mostly about what drugs do to your body: “When you smoke crack or inject coke, you can’t hear for about thirty seconds. All you get is a sound like a 747 landing down the street, or an aluminum train howling past your face. It sounds like water on fire. Like a ghost fight or a panther crying.”

And he wrote about what drugs do to your soul, about letting yourself be molested for a hit, about stealing a woman’s purse in desperate pursuit of the next high. Sanchez was following the standard M.F.A. edict: “Write what you know.” He ripped through 40 pages that day by resurrecting the awful decisions his “lizard brain” made during his own lost teen years.

He had been a hopeless addict — hopeless in the sense that nothing stopped him from using, not family or the endless ricochet between jail, rehab and the streets, and hopeless in the sense that he sometimes saw no point in even trying to escape his hell.

Joshua Mohr’s second memoir, ‘Model Citizen,’ is even more harrowing than his first, ‘Sirens,’ following a grim diagnosis and a Fentanyl ‘freelapse.’

“I was really troubled, I was very angry and filled with despair,” recalls Sanchez, now 30, 10 years sober and living with his girlfriend in his hometown of Tampa, where he has been working in construction while waiting for his debut publication.

As he worked more slowly over the next few years to recapture the magic of that first blast, he repeatedly reread “The Things They Carried,” Tim O’Brien’s seminal story collection about an American platoon fighting in Vietnam. “It is about memory and pain and suffering, and it just stood out to me as something special, born from personal experience, devoid of self-pity but mind-expanding and heart-expanding. I spent a lot of time trying to figure out how he did it and how I could do it in my own way.”

Sanchez’s autofiction has its own distinctive feel, retaining the frenetic energy of his first outpouring. This is not a plot-heavy story — we follow the narrator on his rare drug-free days, but they usually end pretty quickly and he returns to his misadventures, often using and misusing the only people who remain by his side (except for those who are misusing him). He continues frying his brain until he’s calling a friend, saying, “Yo, man, I’m right around the corner … I just need to chill out for a few hours.”

His friend quietly reminds him that he had just left an hour ago, after calling him two days earlier and saying the exact same thing. Three pages and countless pills later, he awakens in the hospital “cold and small in the gown.”

The book’s rawness was not intentional. The velocity surprised even its author. “When I reread it, I thought, ‘Wow, this moved so fast,’” says Sanchez, who as a reader is more drawn to sprawling, omniscient narratives — Don DeLillo’s “Underworld” is a favorite. Sanchez believes a big third-person novel “is lurking within me,” but thinks he won’t be mature enough to write it for years.

“I came to respect the first-person perspective,” he says. “This book is a punishing internal storm … [and] exhausting because of that and because that’s the reality of drug addiction as I experienced it.”

Sam Quinones, author of ‘The Least of Us,’ a followup to his prophetic addiction chronicle ‘Dreamland,’ talks about meth, homelessness and defiant hope.

The narrator, hyperarticulate and self-aware but helpless to change, is unnamed for the first 190 pages; a friend, holding him and hoping to bring him back to life after a binge, finally says the word “David.”

“That was a healing moment of human reconnection, so it just felt right to have a name,” said Sanchez, who hopes readers will feel both the claustrophobia of the self-centered addict and, eventually, the larger view of the beautiful world that emerges.

Narrator David is less funny and more self-serious than real David, Sanchez says. “I could always find the humor in things, but I liked this solemn, tortured version of me for the novel.” Yet they are equals in self-destructiveness. “The robbery and arrest in there, that really happened. It’s the kind of stupid only real people do.”

Sanchez used real settings but fictionalized some events and omitted experiences that didn’t fit the story, including outdoorsy rehab programs in places like Wyoming. He also left out his suicide attempt at 19, even though it landed him back with his family and started him on the path to healing. “I really thought suicide was the only way out for me at the time, but it would have come late in the book and would have felt almost cruel to the reader there,” Sanchez says.

Some memories came easily, like humiliating, mandatory dancing to Richard Simmons videos in rehab and “the paranoia of those weeklong crack binges burned in my brain.”

Others were harder to come by. Writing first thing in the morning, free of electronic or social distractions, helped Sanchez “access emotional memories that I don’t think I’d be able to otherwise.” Yet he didn’t fear diving back into the state of mind he dwelt in as an addict. Time has provided emotional distance, as has his approach to living sober.

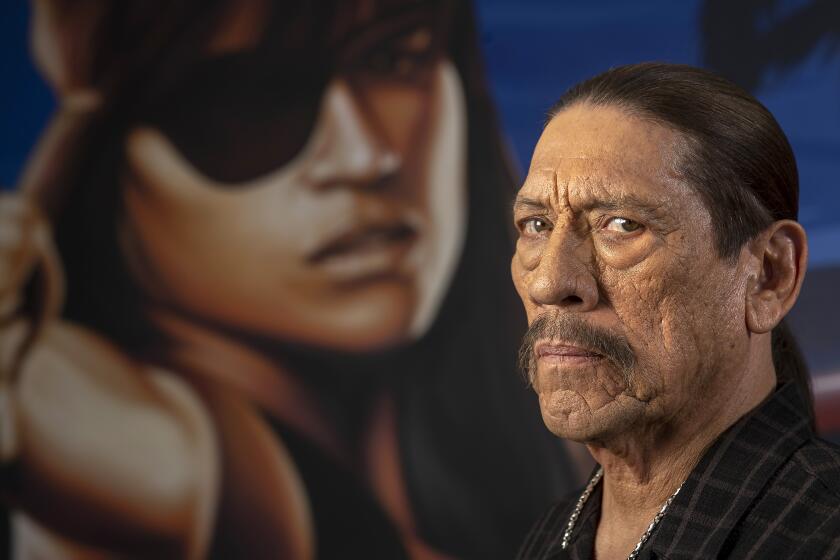

‘Acting wasn’t new to me. I’d acted to survive my childhood,’ writes Danny Trejo in his new memoir. He talks with The Times about his incredible life.

“You try helping someone else struggling with drug addiction, and one of best ways I’ve found is sharing aspects of your life story and having them share with you, so you own that aspect of your life,” he says.

Ultimately, Sanchez says, he embraced the experience: “It sounds crazy to say, but it was almost a pleasure to revisit and rethink and recontextualize all the stuff that had been running around in my brain.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.