Veterans of fruitless wars: Two Marine Corps memoirists share their gratitude and dismay

- Share via

On the Shelf

Veterans' Memoirs

The Education of Corporal John Musgrave: Vietnam and Its Aftermath

By John Musgrave

Knopf: 288 pages, $27

Volunteers: Growing Up in the Forever War

By Jerad Alexander

Algonquin: 320 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

John Musgrave and Jerad Alexander had very different experiences as Marines at war, and they have written very different memoirs.

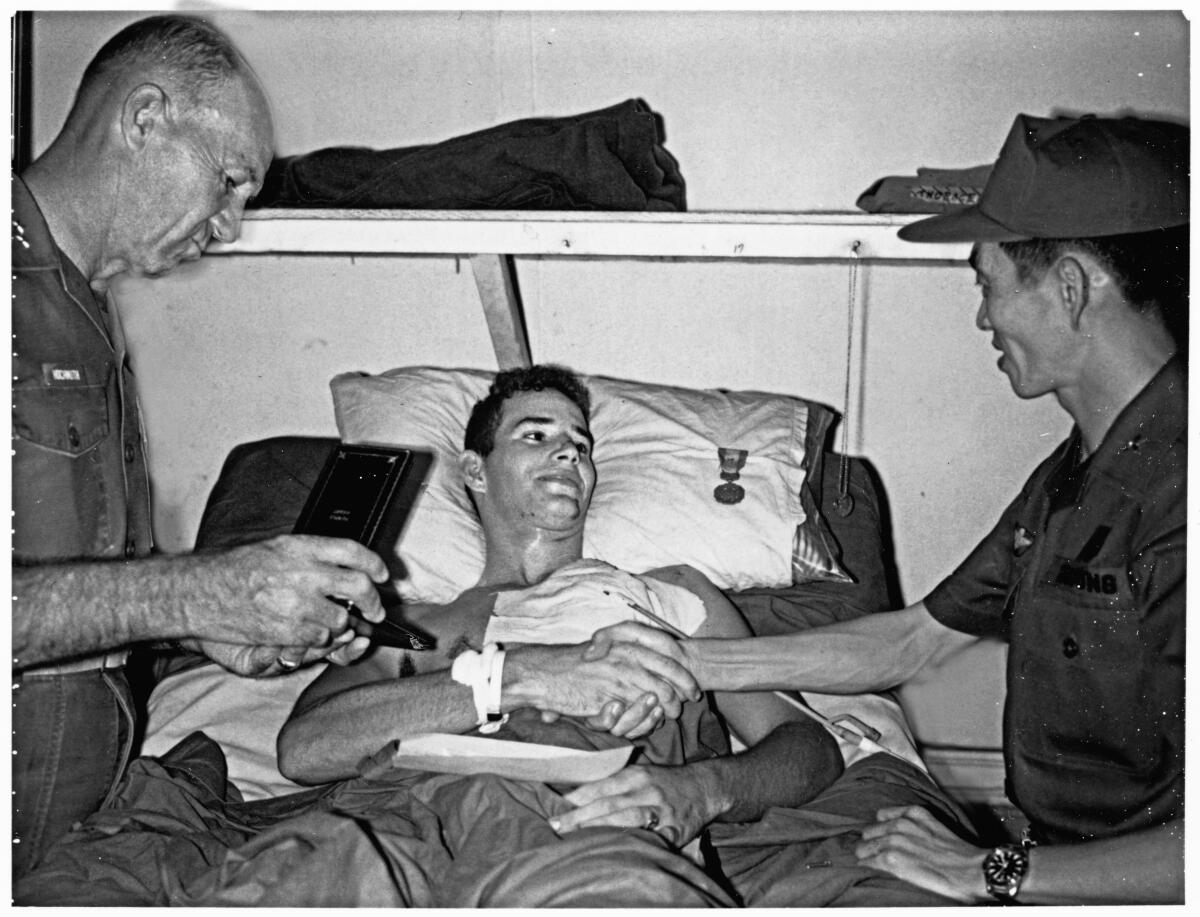

In “The Education of Corporal John Musgrave,” published earlier this month, Musgrave devotes a third of his book to his days in Vietnam, which ended with him getting shot through the chest and dragged to safety by fellow Marines under fire. But the bulk of the rest covers his tumultuous reentry into the civilian world and his growing disillusionment, leading to work with Vietnam Veterans Against the War and other groups in the decades since.

Alexander stakes out his own territory in his new book, “Volunteers: Growing Up in the Forever War.” There are short bursts of action in Iraq, where he was deployed toward the end of his eight years in the Marines, but the book largely recounts Alexander’s childhood in America’s military empire — his family has deep military roots — and how mythmaking and propaganda shaped the views of everyone he knew.

For all their differences, these memoirs share two crucial elements: a skeptical if not cynical view of American politicians who mismanage foreign policy, mislead the public and misuse the armed forces; and, despite that, a lasting bond with their fellow Marines. In the wake of another failed fight — in Afghanistan — the authors joined The Times recently for a video interview, which has been edited for length and clarity.

There is no such thing as “the veteran experience,” particularly in a war on terror waged across multiple countries for more than 10 years.

Jerad, you read books about the horrors of Vietnam, and yet you enlisted. What impact do you hope your books can have on readers?

Alexander: I read James Webb, John Del Vecchio and Tim O’Brien and was motivated to join, when those books should have been shoving me away from it. I understood the war in Vietnam — it sounded like a noble cause, but it was built on a bedrock of lies — and then I walked into Iraq knowing the conflict was built on a dubious premise. I hope the reader will ask, “What it is about war that makes it so attractive? Why would a story that is so terrible propel people to take part?”

Musgrave: There are three main things I want people to get out of my book. First is the extraordinary job the Marine Corps does, taking us in a matter of weeks from being civilians and changing our DNA. And then there’s what plays out on the battlefield, which is that Marines would never leave their wounded, which is the only reason I’m alive today. We loved each other enough to die for each other. I don’t think you can love anybody more than that.

Third is the long, painful process where I realized that the war our government had us fight wasn’t what they told us it was.

John, you wrote about dehumanizing the enemy to survive, a decision that has haunted you ever since: “The dead sleep on your chest.” But could you have survived without doing it?

Musgrave: There was no way for me to escape that. The first time I killed someone was a horrible experience. I thought I was prepared, but I wasn’t. Then I saw my first Marine die and realized I was going to have to make my deal with the devil. You come to the realization that the road home is paved with the bodies of your dead enemies, and you’re not getting home unless you pave it. So we had to find ways to live with it.

Alexander: John’s war was very violent and cruel. What we faced there was nothing compared to [that]. And our approach to the people was a lot lighter. We weren’t all suddenly good, of course, but the military did learn lessons from Vietnam: We heard constantly, every bullet you fire has ramifications for the next Marine; if I cause harm to someone who is undeserving, that could cause harm to a Marine later.

Is war part of human nature — or men’s nature — or is it avoidable?

Musgrave: As long as we have enemies, we’ll have war; unfortunately, we have a lot of enemies. You just hope we learn from our mistakes because our mistakes cost us our most valuable treasure — kids who believe in their country.

Alexander: It’s part of the human condition; we have a caveman-like tribal instinct to fight. The way to curtail it is to examine it clearly, explore the ugly sides of it and the noble sides — and there are both. If we ignore it because it says too many uncomfortable things about ourselves, then we repeat the same cycles, fighting wars for no reasons or for terrible reasons.

An account of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq that deserves a place in humanity’s long tradition of war reportage.

John notes that we haven’t won a war since 1945. How should that inform future military actions?

Musgrave: The definition of war changed in August 1945 when we dropped those two atomic bombs. War is something you’ll do anything to win, so we haven’t really had one since.

We should enter conflicts understanding how we’re going to get out of them. We should decide what we’re willing to invest and where we’re willing to draw the line — whether it’s a military victory, a political settlement or running off to the last helicopter out of town. We won the fight against Saddam [Hussein] and had no plan after that and the country went to pure anarchy, and we were the devils.

Letting our military handle our wars might not be such a bad idea because the civilians have [mucked] it up since 1950. Maybe we should let the professionals have a swing at it next time. Most of all, I’d like us to choose a lot more carefully before we send our kids in.

Alexander: I would push back against what John said about allowing the military to make the decision. That’s probably not the best move. Generals were leading the Afghanistan war for 20 years. But he makes a good point about us not winning a war. Except for slivers of the Afghanistan fight early on, I’m not fully convinced we’ve fought for legitimate American interests since World War II. We’ve been fighting for other nations’ freedoms — there’s a certain righteousness to that, but the American public doesn’t have to engage fully because we’re fighting for someone else, not for us.

How did you react to the disaster in Afghanistan over the summer?

Musgrave: To see these young men and women [gets choked up] put in an impossible situation, getting 13 kids killed so the president could get out on the exact day he wanted — it just made me sick. We’ve seen it all before, on the roof of the U.S. Embassy and with the tragedy of the Vietnamese boat people. It was hard to watch and know we hadn’t learned a damn thing.

Alexander: That’s the most maddening attribute. This is not new ground. Withdrawing from a battlefield or a country is a struggle to do in the best circumstances, but how do you have 20 years of war and not plan what you’re doing better?

But I get angrier about the idea of fighting a war on the cheap with no public involvement, with a half-done foreign policy flown in. We made this decision: If we keep it low-powered, the American public won’t get upset, and we can keep this dubious equilibrium and sustain a conflict while lacking a commitment. Do or do not, but don’t just float in halfway because you end up expending lives for nothing.

Musgrave: Amen.

Robert Draper has written an authoritative account of the deceit and misjudgments that the George W. Bush administration used to lead America to a ruinous war.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.